In the new book “Superheroes!: Capes, Cowls, and the Creation of Comic Book Culture,” Laurence Maslon and Michael Kantor trace the history of superhero comics and the way they moved from children’s entertainment to a central aspect of popular culture. Based on the PBS mini-series, the book includes interviews with many of the key players in that history, as well as gorgeous images. The following excerpt covers the remarkable transformation of the industry by a new generation of artists and writers in the 1970s and ’80s, and how that caught the attention of Hollywood.

GENIES OUT OF THE BOTTLE

The Corporatization of the Comic Book Industry

Since the late days of the Depression, the comic book industry had been comprised of several immutable constants: the firms had been run by professionals who had their roots in the publishing and distribution business; the companies were based in New York; they were relatively small in nature, staffed largely by middle-aged adults who usually commuted at night to homes in the tri-state area, where they sat in armchairs and read literature other than comic books.

That would all begin to change in the early 1970s, when a new generation of comic book writers and artists entered the field, former fans who had grown up with the medium and were eager to intertwine the adventures of their favorite superheroes (or at least the superheroes they were assigned by their middle-aged editors) with the issues of their day: Denny O’Neil, Neal Adams, Gerry Conway, Len Wein, Marv Wolfman. “For a long time,” said Conway, “we’d say that comics were going to be dead in ten years. By the late ’70s, enough of us probably believed that that we started saying, well, maybe we better find other ways to make a living.” Some of the ’70s superstars (Conway, Wolfman) would follow Stan Lee’s lead (once again) when he moved to Los Angeles in 1981, in his case to pursue new venues on behalf of Marvel in film and television. O’Neil and Wein would stay in comics, but expand their acumen to edit the work of newer, edgier talents.

These creators left the field to the next generation—writers and artists who had been inspired by their attempts to make comic books more relevant. A surprisingly large number of the next generation’s most spectacular talents came from the United Kingdom, largely from the northern part of England. They included Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, Dave McKean, Dave Gibbons, and Mark Millar, young creators who expanded into other non–comic book areas such as punk music, novels, graphic design, and the occasional dabbling in occultism.

The diverse and non-mainstream backgrounds of these U.K. artists helped to transition the increasingly dull comics of the mid 1980s and 1990s into frequently surprising departures from the norm. “It was time for us to come along. The American comic had become focused on this scorecard mentality,” said Morrison. “Is the Thing stronger than the Hulk? It was a very strange time. It became almost like stamp collecting.”

As different as Morrison’s generation of creators was from their predecessors, the biggest change may have been in the consumer base. As comic books moved through their sixth decade, it became clear that many longtime readers weren’t going anywhere—they were reading comics into their thirties and forties and they didn’t want to read the same old stories where the Flash foils the Mirror Master from robbing a bank. They wanted growth and development, just as they themselves were growing and developing. “So you have this conflict between the desire of an ongoing readership and the nature of these superhero characters which is static,” said Conway.

The maturing audience encouraged the new brand of creators to venture into more complex territory—much of it darker than the usual superhero fare, playing into the stereotype of the “grim-and-gritty” era. The comic book publishers, realizing that their audience was diversifying, created discrete imprints for this mature work. Vertigo Comics, an imprint marketed as “suggested for mature readers” and including well-received titles such as Gaiman’s psychological fantasy series, The Sandman and Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta, found a home at DC Comics. Epic Comics was Marvel Comics’ repository for creator-oriented titles that explored mature storylines outside of the Marvel Universe, often without the approval of the Comics Code (Marvel followed Epic with another mature-themed imprint, MAX, in 2001). A new venue emerged for expanded, more complicated superhero-oriented tales: the graphic novel.

There had always been attempts at expanding comic book storytelling into longer, non-serial, self-contained forms—the burst of sword-and-sorcery one-offs in the early 1970s, for example—but publishers realized there was a new market for one-shot tales, as long as the characters were familiar and the printing of the books (often hardbound and softbound, concurrently) exhibited the durability of a novel, rather than the transience of a pulp comic book. One of the most successful of these early attempts was Grant Morrison and painter/illustrator Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (1989), a format-shattering tale of Batman encountering a dark night in Gotham City’s most famous (and not terribly competent) madhouse.

The trade paperback was a “win-win,” giving publishers another venue in which to print (and reprint and re-reprint) popular stories, while allowing literary critics to take the non-disposable publications seriously. Perhaps no other publication benefitted more than Moore’s Watchmen, which was placed on Time magazine’s list of “The Hundred Greatest Novels Ever” in 2005—the only comic book narrative to earn that honor—and eventually moved millions of copies. But neither Watchmen nor The Dark Knight Returns nor a host of other “graphic novels” were actually graphic novels; they were paperback (or hard-cover) compilations of material that had appeared previously in serial comic books, a distinction that was largely lost. Alan Moore personally detested the lack of clarity: “The problem is that ‘graphic novel’ just came to mean ‘expensive comic book’ and so… [DC or Marvel would] stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel.”

Be that as it may, there were vast new marketing possibilities for ancillary material. Some of this was because both DC and Marvel would be folded into larger and larger conglomerates as the 20th century drew to a close. The DC stable of characters benefitted from a well-orchestrated corporate transition when Warner Communications—which had already been instrumental in bringing Superman to the big screen through their film studio connections—merged into the mammoth corporation of Time Warner in 1990.

Since the success of the Superman film in 1978, there had been a slow, but relentless, drive to put Batman back on the screen, and Warner Bros. was the obvious studio to make it happen. One of the early producers on the project, Michael Uslan, thought it was time to break through the campy veneer that had kept Batman from the larger public he deserved. The Miller Dark Knight saga gave the embryonic project the credibility it needed to move forward, and in 1988 Warner Bros. hired idiosyncratic filmmaker Tim Burton to bring Batman to a new generation. According to writer Grant Morrison:

Tim Burton related Batman to things that were happening then—the fetish underground, the transgressive elements, the Gothic elements which were coming out of music as well. There was a real heavy punk element to the whole thing and Batman very quickly adapts to that; he was a black leather figure in a cave.

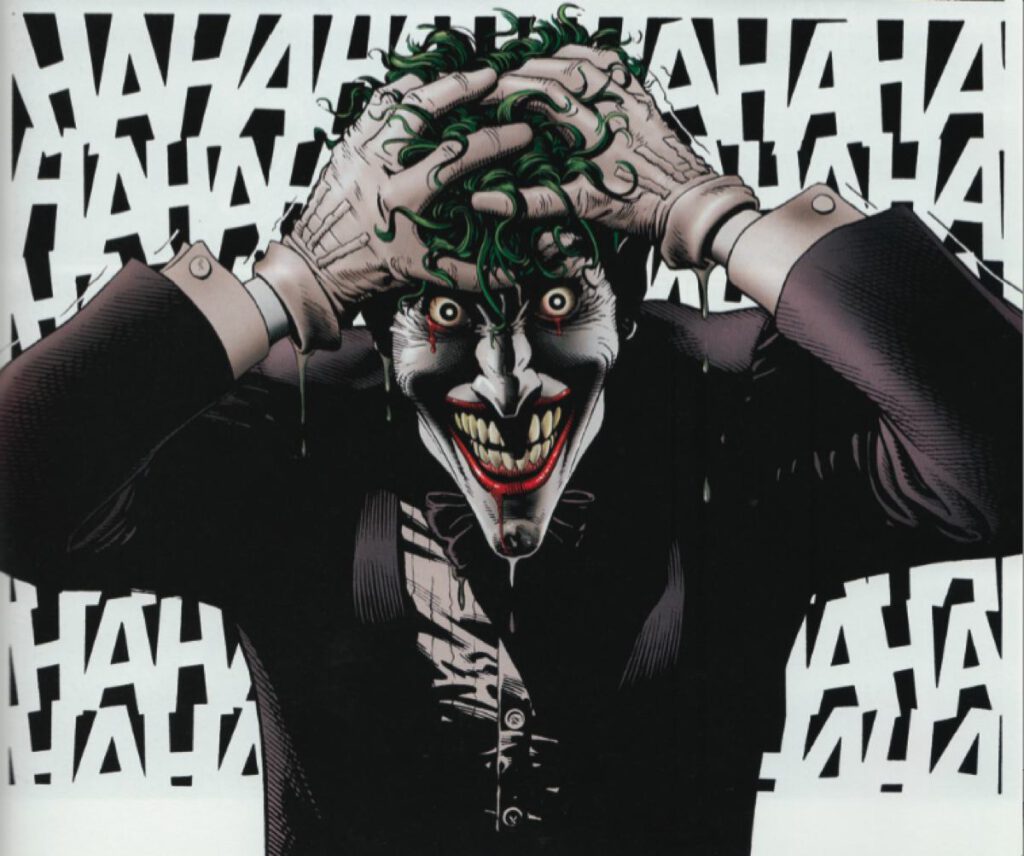

Burton was not a comic book fan—he claimed he never knew how to follow the way the panels moved on a page—but he was inspired by another progeny of the Dark Knight saga, a one-off graphic novel from 1988 called Batman: The Killing Joke. A terrifying story of the Joker at his most disturbingly deranged, it was illustrated by Brian Bolland and written by Alan Moore. Moore and Bolland’s Joker would provide the inspiration for Jack Nicholson’s brilliant portrayal in the Burton film. The final result, Batman, released as a tentpole blockbuster in summer 1989, racked up an astounding $150,000,000 in its initial domestic release, and led to three sequels (of variable quality). Through their association with Warner Bros., DC Comics proved they could deliver first-rate films based on their signature characters.

Marvel, on the other hand, seemed to have nothing but bad luck; its parent organization was bought by Revlon founder and stock market whiz Ronald Perelman in 1989; eventually, due to some bad moves with affiliated companies, the complex corporate entity that owned Marvel Comics and its characters filed for bankruptcy.

During this time, Marvel kept trying to expand its reach in various marketing fields such as action figures and video games, but the Holy Grail of a blockbuster film or two had eluded Marvel completely, despite Stan Lee’s best efforts as ambassador-with-portfolio in Hollywood. Marvel sold the rights to some of its most famous characters for bargain-basement prices to independent studios on the lowest end of the food chain. Despite a much-trumpeted deal in 1990 with filmmaker James Cameron to bring Spider-Man to the screen (which never happened), Marvel was stuck with dogs so cheaply made (The Punisher, Captain America) that they barely made it onto videocassettes. Most embarrassing was the 1994 version of The Fantastic Four, which was made (for a rumored $1.5 million) only to hold onto the screen rights: the final dismal result was never meant for commercial distribution.

Marvel would eventually find its groove in Hollywood by the 21st century, but the late 1980s represented a massive sea-change in the comic book business, a Super-genie that would be impossible to put back into a bottle—even a bottle as large as the one that holds the city of Kandor. For Gerry Conway, the corporate evolution of the industry was the biggest game-changer of all:

While we loved what we were doing in the ’70s, I don’t believe we thought that it mattered and certainly our publishers didn’t think that it mattered. If a particular issue didn’t do well, that was fine, there was next month. We didn’t have this sense that careers revolved around choices that you make for this particular character a year in advance. I think that’s a creative soul-killer for the business.

Excerpted from SUPERHEROES: Capes, Cowls, & the Creation of Comic Book Culture. ©2013 by Laurence Maslon and Michael Kantor. Reprinted by permission of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company.

Photos: Fantastic Four: Photofest; Joker: DC Comics; Ronin: DC Comics