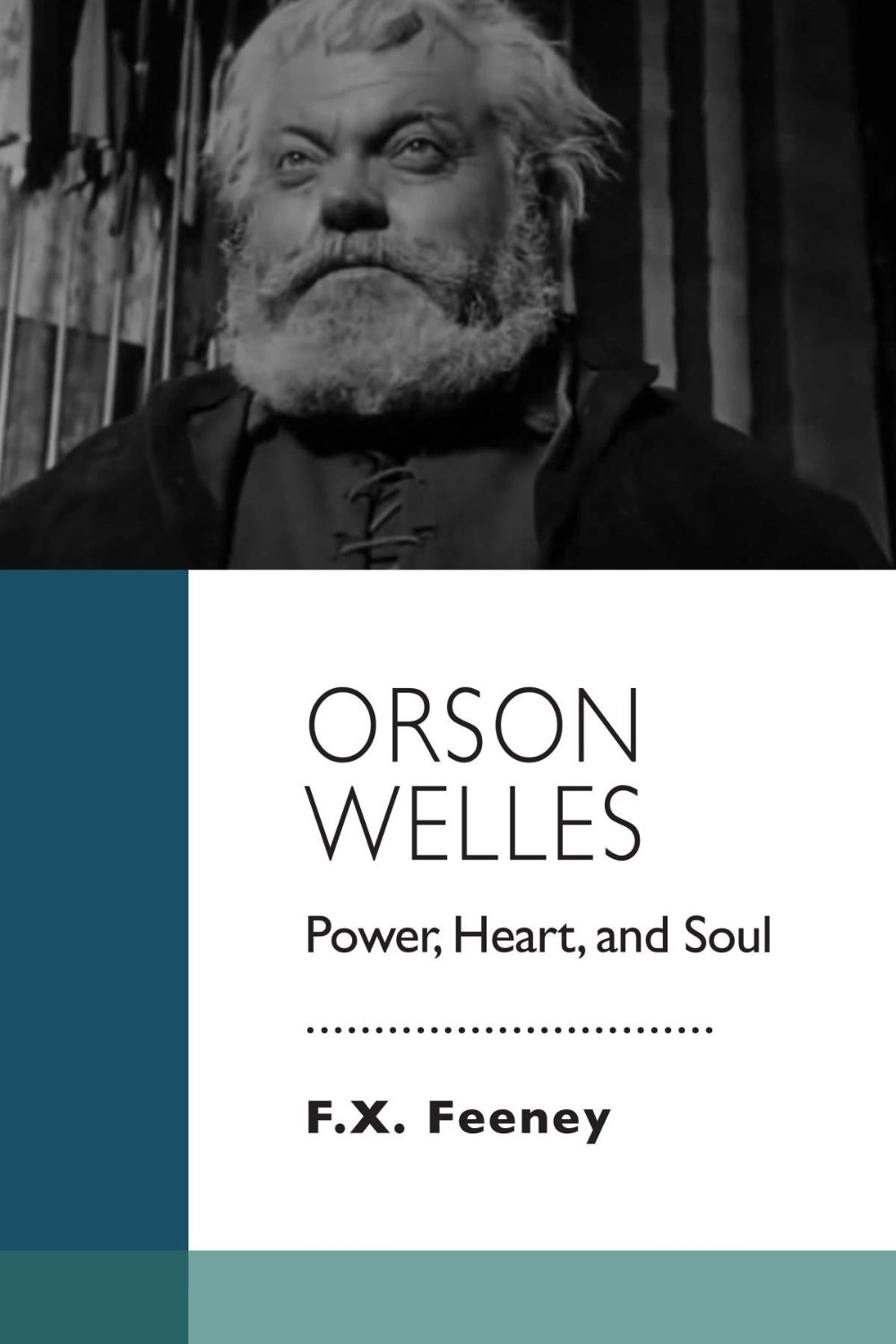

Critical Press released a book this week on the legendary Orson Welles and we’re proud to present an excerpt. You can pick up a copy of the full book here.

Synopsis: This incisive introduction to the life and work of Orson Welles is an essential study of one of the most important American artists of the twentieth century. With special attention paid to the political, social and cultural milieus in which Welles lived and worked, this in-depth personal essay and biographical portrait brings to life a filmmaker who is too often either mythologized or misrepresented, fully humanizing the man behind masterworks like “Citizen Kane,” “The Magnificent Ambersons,” “Chimes at Midnight,” and many more.

Mastery in Midlife: Orson Welles

and Chimes at

Midnight

A few years after completing “The Trial,” Welles charmed Spanish producer Emiliano Piedra into financing an adaptation of “Treasure Island,” on the peculiar condition that “Chimes at Midnight” be filmed with it, back to back, using the same sets. Piedra was more interested in “Treasure Island.” Welles made a few elegant Technicolor shots of a pirate ship and another few of himself waddling peg-legged down a beach with a parrot on his shoulder. Piedra was pleased, but then black-and-white footage began to flood in, in which the pirates (if one could call them that) were spouting Shakespeare. Before he could object, a week of this bawdy intrusion was in the can.

The world owes Señor Piedra an immense debt for his forbearance—as well as his partners Ángel Escolano and Harry Saltz- man—for “Chimes at Midnight” stands shoulder-to-shoulder beside “Citizen Kane”. Side by side they constitute the twin pillars of his life’s achievement—”Kane” being the summit of Hollywood studio artistry; “Chimes” being the most fully realized example of Welles’s hard-won independence, a masterpiece that unfolds in its own self-created system. Shakespeare’s language is done the rugged honor of being spoken quickly, lightly, as if it were colloquial English. The soundtrack, while superbly mixed, nevertheless suffered from poor reproduction in the first release prints; the first reel was slightly out of sync by eight frames. Yet despite such modest challenges, the film gives us Welles at his most open, generous, and human—both as a director and as an actor.

He worked rapidly and with confidence. There are no complex master shots—the story unfolds in quick cuts. For production design he relies chiefly on the wonders that were available in contemporary Spain—the spectacular interiors of the royal palace at El Escorial and other jumbled, cobbled streets dating from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. If an actor such as John Gielgud was only available for a handful of days, Welles concentrated on him entirely, using stand-ins for distant and over-the-shoulder shots, just as he had on “Othello,” but with the vital difference that this time he wasn’t taking years to conjure these clever effects but weeks. He knew exactly what he was doing from moment to moment—and that muscularity comes across. Angelo Francesco Lavagnino’s exuberant musical score communicates this energy beautifully.

The succession of English Kings is at a delicate impasse. King Henry IV (John Gielgud) came to his throne by force, and is beset by the Percy clan, who are its rightful heirs. Foremost among is a fearless rebel nicknamed “Hotspur” (Norman Rodway). King Henry looks upon this upstart with a helpless attraction—his own son is a disappointment to him. Cut to Prince Hal (Baxter) bending his elbow at the Hogshead, where he cuddles bed-sheeted whores and plays pranks on his mentor, Falstaff (Welles). The first half of Chimes at Midnight revolves around these contrasts, and what is hidden within them. Hotspur is winning and attractive—yet Welles hints that he belongs to a dying age. Where Hotspur dreams of honor, Hal is a student of mortality, a fact before which even honor must bow. Hal is, in any case, enjoying what little natural life is to be granted him before he must take the crown and assume a mantle of so-called greatness. “I know you all, and will awhile uphold the unyoked humor of your idleness,” he says softly, as if talking to himself but with Falstaff within earshot. There is an unspoken pact between Hal and Falstaff in this moment. The prince has enjoyed more fatherly love from this fat, life-loving renegade than he will ever know from his actual father—but what must be, will be. Falstaff’s steady gaze in reply signals that he knows (hoping against hope that it won’t come to this) and is ready, even for betrayal, if need be.

Such fatalism lends a dimension of melancholy to what follows. In this, “Chimes” is kin to “Ambersons.” We’re asked to suspend judgment. There are no villains here—only tragedies, and comedies, acted out against a starry firmament of virtues and vanities. We’re witnesses to an immense, bloody battle. Welles achieved this sequence loaves-and-fishes–style, making a dozen extras look like a hundred and a hundred look like a thousand, through ingenious shooting and cutting. Hal and Hotspur face each other in single combat, and the fate of a kingdom is decided. The emotions underlying this moment are profound. The two men are both so comparably gifted, so fraternally aligned, that in a just universe they would be the best of friends. Both know this. (And Shakespeare’s dialogue rises to exquisite heights in the expression of it.) And yet, as men who each, singly, must be King, they each accept the unjust nature of the universe and get to work putting the other to death. “O Harry, thou hast robbed me of my youth,” smiles Hotspur, as he lies dying. “Fare thee well, great heart,” replies Hal, standing over him in cold triumph. “Ill-weaved ambition, how much art thou shrunk! / When that this body did contain a spirit /a kingdom for it was too small a bound. / But now two paces of the vilest earth/ is room enough. This earth that bears thee dead, / bears not alive so stout a gentleman.”

Welles explored the mysteries of power in “Citizen Kane,” and those of family and fate in “The Magnificent Ambersons”. In “Chimes at Midnight” he devised from the fabric of Shakespeare’s genius a structure mighty enough to fuse the great themes of his life, as if once and for all. His calm confidence at the heart of it animates every performance. Gielgud speaks Shakespeare with the airborne, unselfconscious freedom of a man singing to himself in the dark, in his native tongue. Keith Baxter’s ability to wear a private face in public brings a self-mocking irony and a mystery to Hal which makes the character a twin brother to Hamlet. Jeanne Moreau jarred the film’s more dull-witted critics in 1966 with her French accent, but as Doll Tearsheet ably and sensuously loves Falstaff on the audience’s behalf. Margaret Rutherford as Mistress Quickly; Norman Rodway as Hotspur; Alan Webb as Master Shallow, and the mob of faces and voices whirling about the action, are marvels of grotesque exaggeration and the most humane tenderness. Ms. Beatrice Welles, age nine, passes neatly for a boy—she plays Falstaff’s page, and with her clever Wellesian eyes is a perfect, cupidlike embodiment of Falstaff’s soul-essence.

Welles himself has never been greater, as an actor—the look of recognition and surrender when he is embarrassed by the new King, his beloved Hal, stands beautifully for every indignity anybody has ever suffered with grace. “If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie, [“Chimes at Midnight”] is the one I would offer up,” he said near the end of his life. The close-up he gives himself at this moment is the most unguarded of his career. He, who had wished so much power for himself, preferred now to surrender all power, heart, and soul, on another’s behalf. For the first time, he has made a successful love story—one true to love as it is most deeply defined in either this world or the next, be it as courage, compassion, or sacrifice.