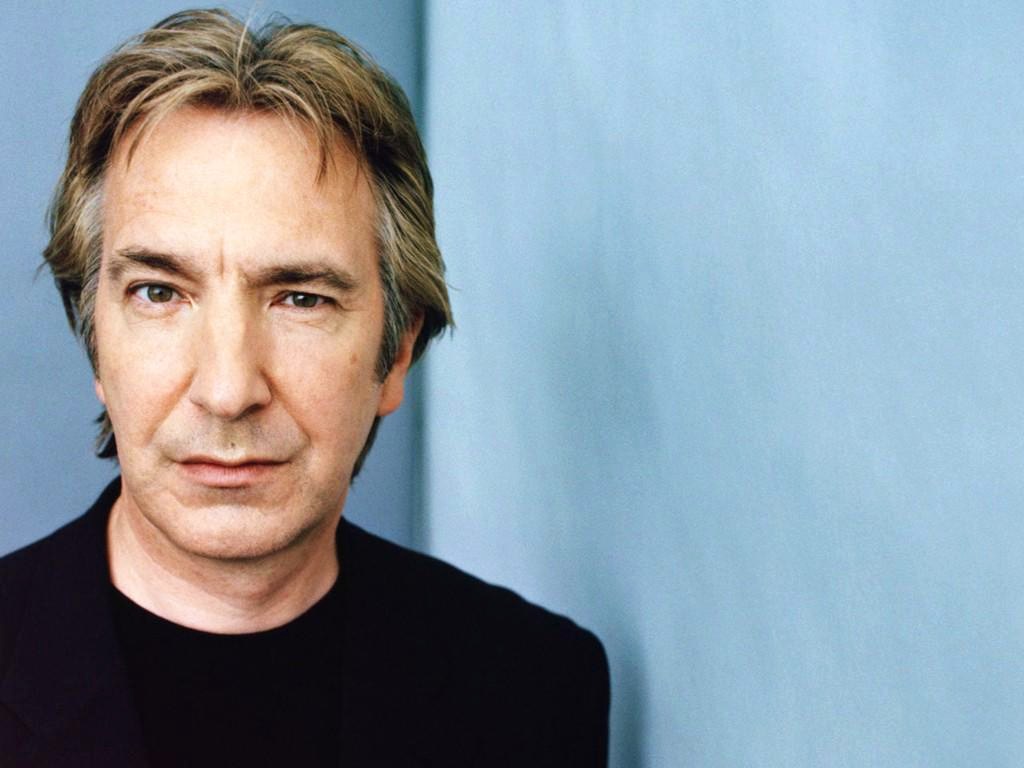

Alan Rickman didn’t just speak: he chewed words, he rolled them around in his mouth before letting them go, he relished them. He drew out syllables, he held onto consonants (who can hold onto a “t”? Or an “n”? Alan Rickman could and did). His impeccable vocal style, so unique to him, was a mark of his theatre training at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, as well as his years performing in theatre, his first love. Perhaps the sinewy sensuousness of his voice, made so startling when mixed with the clipped or elongated consonants, was why he was seen as so perfect for villains and sneering manipulators. But some of his best work was when playing men who ache with warmth, men with depths of tenderness. In those contexts, Rickman became a classical Leading Man, and the distinctive voice sounded instead like molten lava, exploding through the hard crust of his exterior. Rickman could be heartbreaking. He could fit in in a fantasy context, a real context, a 19th century context, a 20th/21st century context. His access to himself, to all aspects of himself, the cruel, the tender, his humor, his sexuality (or its repression), is why his career lasted 40 years, and why he was never out of work from the day he began.

Rickman started out as a graphic designer; he studied at the Chelsea College of Art and the Royal College of Art. Afterwards, he opened up his own graphics design operation, running it for a couple of years, before deciding to audition for the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. He was 26 years old. This is late to “get started.” It’s an intriguing detail about the man. He walked away from a career he had devoted himself to, another craft he was good at, into the sheer uncertainty of show business. He chose acting deliberately. When he started out in theatre, he wasn’t playing young male leads, as is the case with the 20-year-olds who flood the market every couple of years. He started out playing leads. He was already slightly-seasoned, his gimlet-eyes filled with experience. He would not have to waste his time playing “innocents.”

Rickman’s first break in America was in the 1987 Broadway production of Les Liaisons Dangereuses where he played the Vicomte de Valmont (John Malkovich’s role in the film) opposite Lindsay Duncan as the Marquise de Merteuil (Duncan was to be his co-star again in the celebrated 2002 Broadway revival of Noel Coward’s Private Lives.) Rickman won the Tony Award for his performance. The following year, he made his unforgettable American film debut as the mastermind villain Hans Gruber in the “phenom” that was “Die Hard.” His shadow immediately stretched out across the landscape, because everybody saw that movie, everybody remembered him, everybody loved the delicious deliberation of his line-readings, his psychopathic unconcern for collateral damage.

Rickman could have had a nice career playing villains. But 1990’s “Truly Madly Deeply”, directed by Anthony Minghella, upended expectations. Rickman played Jamie, the ghost of Juliet Stevenson’s dead lover. Stevenson’s character had been grieving the loss for a year, and one night she sits down to play the piano. As she plays, a cello suddenly starts up off-screen, and “Jamie,” who had played the cello in real life, is seen sitting behind her. The reunion that follows is one of such wrenching emotion that it puts “Ghost” to shame. It’s barely romantic. They clutch and hold, they weep and coo, they sob. As “Jamie,” Rickman is both hilarious (he’s always freezing, always cranky) and tragic (if she can’t let him go, then he really can’t let her go.) An entire new world opened up for Alan Rickman, at least in terms of the audience who had only seen him in a gigantic blockbuster as a multinational terrorist-villain. When Jamie says to Nina, “Thank you for missing me,” his tone is quiet and thoughtful, but Rickman filled the line with a sense of almost humility: “This fabulous woman grieved ME this intensely? I have this much value?” His line-reading cracks open the heart of the film.

Throughout the years, Rickman flowed back and forth, and up and down, within his own gift, drawing out one quality while holding back others, like a maestro. The story dictated his style. He was a true professional. There was no ego in his work.

In 1995, he appeared in Ang Lee’s “Sense and Sensibility,” although the genesis of that project was Emma Thompson, who had adapted Jane Austen’s novel. Rickman played the upright Colonel Brandon, a man so proper, so perfectly-mannered, that he practically blends into the furniture. Perhaps the key to Rickman’s effectiveness in the role is that there is no self-pity in the portrayal (self-pity would have wrecked it). You have to believe that Colonel Brandon, though he may lack the fireworks of Willoughby (Greg Wise) can provide Marianne (Kate Winslet) with something far more substantial.

One of the most powerful moments in the film belongs to Rickman. Marianne has fallen deathly ill and the doctors have given her up. Brandon pulls Elinor aside and asks what he can do. Elinor puts him off, assuring him he has done enough, and Brandon, pressing himself back into the wood-paneled wall, almost as though he needs it for support, bites out the next line: “Give me an occupation, Miss Dashwood, or I shall run mad.” This is the “molten lava” effect of his voice, sentiment pouring out of a man unused to displays of emotion. It’s a marvelously rich performance, and it works as a stealth-bomber in its effect. Willoughby has the flash, Marianne has the emotion, Elinor has the tightly-coiled repression, and all of the secondary characters are extreme buffoons. But Colonel Brandon has the heart hidden in his chest, a flame flickering low before exploding into brightness. It is difficult to imagine any other actor in that part.

Through the ’90s, he appeared in films big and small: “Galaxy Quest,” “An Awfully Big Adventure,” “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves.” He worked with Neil Jordan in “Michael Collins,” playing Éamon de Valera, Fianna Fáil founder and later the President of Ireland, a stroke of genius casting, the two men look so much alike. He was so entertaining in Kevin Smith’s “Dogma“, playing the pissed-off bedraggled angel Metatron. When he first appears in a girl’s bedroom, as though he’s just woken up from a bender, she brandishes a baseball bat at him, yelling for him to get out. He replies, threateningly, “Or you’ll do what exactly? Hit me with that ffffffffffish?” (The baseball bat turns into a fish.) Again, who would choose to draw out the “f” like that? Drawing out the “f” makes what might have been a stupid visual joke something eccentric, character-driven, and much much funnier. Rickman explored the nooks and crannies of language, finding possibilities where there were none before.

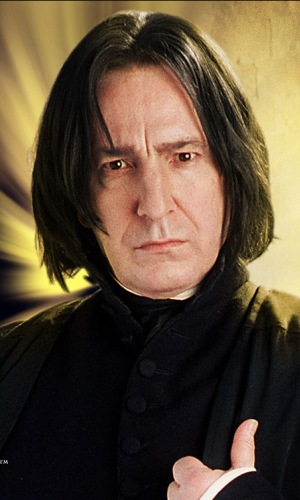

J.K. Rowling has said that as she was writing the “Harry Potter” books, she had Alan Rickman in mind already as the deliciously sinister (and also ambivalent) Severus Snape. He inspired her as she was creating it. Rickman’s “look” as Severus involved a dandyish pitch-black pageboy, reminiscent of John Cazale’s in “Dog Day Afternoon” or Javier Bardem’s in “No Country for Old Men.” It’s a demented mop-top. Released from the demands of realism, Rickman sinks in, deep in, to Severus, every reptilian glance, every flicker of the eye, every murmured aside, every outraged nostril-flare, pouring into the overall effect. The performance is not an amalgamation of broad tics. It appears lived-in and felt, which makes it even more absurdly pleasurable. Younger audiences who had never seen “Die Hard” got their first glimpse of what older generations knew all along: this guy could do anything. Anything.

Rickman also wrote and directed two films, 1997’s “The Winter Guest,” starring Emma Thompson and Phyllida Law, where he showed a sensitivity to atmosphere and mood as a director, and last year’s “A Little Chaos,” starring Kate Winslet, in which Alan Rickman himself plays The Sun King. I haven’t seen “A Little Chaos” yet, but the thought of Alan Rickman as King Louis XIV already fills me with excitement.

Throughout the ‘aughts, in between “Harry Potter” movies, he continued to work steadily, showing up as Ronald Reagan in Lee Daniels’ “The Butler,” Hilly Kristal in “CBGB,” Judge Turpin in “Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street,” as well as providing voices for various animated characters. He never stopped returning to the theatre as well, and anyone who was fortunate enough to see him onstage is so thankful for that.

In 2002, my friend scored tickets for us for the Broadway production of Noel Coward’s Private Lives, starring Alan Rickman and Lindsay Duncan, reunited again after Les Liaisons Dangereuses 15 years before. Private Lives was only running for 16 weeks, and it became one of those rarities in New York theatre: an “event.” Private Lives had sold out during its run in London, and the buzz crackled to theatre-goers across the Atlantic. When tickets went on sale, my friend was ready.

That production is one I will never forget. I see a lot of plays, some good, some okay, some forgettable. But a production like Private Lives doesn’t come along all that often, and even as the play was happening, I remember thinking, “I am so glad that I will get to say that I saw this.”

Community-theatre productions and acting-class workshops of Private Lives often focus on the dazzling wit of the divorced Elyot and Amanda, who meet up again while they’re on their respective honeymoons to new people and throw brilliant barbs at one another from their balconies. But without the strong rope of connection existing between these two jaded sophisticates, the play does not reveal itself. It would be like “His Girl Friday” without the chemistry between Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell. The audience has to see that the characters are meant to be together, along with the underlying question: who else would put up with these two maniacs?

Alan Rickman and Lindsay Duncan were so confident in that difficult language that when I went home I pulled out the play again. I wanted to re-experience the miracle of how they filled that language, made it seem like they were speaking off the cuff. Rickman and Duncan created a breathless sense of eroticism between them, the magnet of chemistry so strong that they must beat one another back with linguistic barbs. The reason they are so vicious is not because they are mean or because they are “sophisticated,” it is because they can barely bear the heat of one another’s presence.

Seeing Rickman live was a revelation. Some movie actors disappear in large theatres: without the helpful cinematic closeup, they are lost as to how to project emotion. Rickman’s emotion in Private Lives was in his eloquent posture, upright in the first act, and lounging with satiation in the stunning opening of the second. It was in that voice, that beautiful fluid strange voice, so well-known to audiences in all its flexibility. His voice was even more of an amazing “instrument” onstage than it had been in film. I have always cherished him for his voice, but in Private Lives, he used it to express what was in Elyot’s bitter proud heart so that I, sitting 10 rows from the back of the theatre, could hear it and feel it in my bones. Not to be tried by amateurs.

Alan Rickman was only 69 years old when he died. He would have continued working into his 80s, or beyond, had he lived. He was that kind of actor. He would never have stopped pleasing us, surprising us, intriguing us. He didn’t make a spectacle of his work ethic, he didn’t strain for Oscar nominations, he didn’t have careerist concerns. He did the job brilliantly, went home, appeared in a play, directed something, came back to do another film role brilliantly, went home, and on and on.

A true pro.