Q. I have noticed lately that you have been getting softer on bad movies (compared to the general critical consensus and my tastes, too). These movies include “Garfield: The Movie,” “The Stepford Wives” (2004) and “The Day after Tomorrow.”

I had the displeasure of seeing two of these three, and they did not deserve even one of your precious stars. Of course I could be imagining things, but it just seem like lately you have been more sympathetic to bad movies. If this is true, why? Daniel Mills, Alameda, Calif.

A. In my reviews I tried to give specific reasons why I enjoyed those movies: Bill Murray’s voice-over work as Garfield, the witty “Stepford” dialogue and the remarkable special effects in “Day after Tomorrow.”

All three movies were flawed. In the case of “The Stepford Wives,” I should probably have praised the dialogue but cranked down the stars. “Garfield” we can debate. I was absolutely right about “Day after Tomorrow.” I was also right to dislike “I, Robot,” despite the “general critical consensus,” etc.

Q. In your review of “I, Robot” you stated that the movie should have credited Isaac Asimov as the creator of the famous three laws of robotics. However, within the fictional universe of “I, Robot,” the three laws would have been created by a fictional someone.

Much like Shakespeare was the one who wrote “But Brutus says he was ambitious/And Brutus is an honorable man,” but within the fictional universe of “Julius Caesar,” it was Antony who said it. If Brutus were to refer to that quote, he would cite Antony as saying it, not Shakespeare. In the same way, since the fictional Dr. Lanning wrote Asimov’s Three Laws within Asimov’s fictional universe, it is accurate to say Dr. Lanning wrote the three laws. Brian Valentine, Lake Wales, Fla.

A. I got lots of complaints about that. Here is what I wrote: “The dead man is Dr. Alfred Lanning (James Cromwell), who, we are told, wrote the Three Laws. Every schoolchild knows the laws were set down by the good doctor Isaac Asimov, after a conversation he had on Dec. 23, 1940, with John W. Campbell, the legendary editor of Astounding Science Fiction. It is peculiar that no one in the film knows that, especially since the film is ‘based on the book by Isaac Asimov.’ Would it have killed the filmmakers to credit Asimov?”

From a logical point of view, you are absolutely right. From my point of view, my tongue was in my cheek. Not everybody appreciates irony. Several readers helpfully informed me that every schoolchild does not, in fact, know about Asimov’s conversation with Campbell.

Q. Regarding the Bush campaign’s new TV ad, “Kerry’s Coalition of the Wild-eyed”: I linked to a script of the spot, and noticed that they are using what’s described as a “video clip” from the 2003 Oscars, when Michael Moore berated George W. Bush.

I’ve always understood that Academy is extremely vigilant about protecting its copyright, and permits clips from the Oscars to be rebroadcast only in very special cases (for example, when a presenter or recipient dies). If the Oscar clip really is in the Bush ad, does this mean AMPAS has relaxed its licensing/usage policy? If not, will its leaders demand that Bush & Co. cease and desist? Stuart Cleland, Evanston

A. Bruce Davis, executive director of the Oscars, replies: “Your correspondent is correct that the Academy prefers that the copyrighted footage from its shows be reused — following the brief grace period immediately after each broadcast — only in the context of obituaries or definitive biographies. We are not enthusiastic about clips from our broadcast being used in political ads, whether they’re blue, red, green or any other hue, but we’ve been advised by our attorneys that the clip in the Bush ad is short enough, and oddly enough political enough, to be protected under the fair use doctrine.

“Fair use trumps copyright infringement. So while we’re not happy about what we regard as a misappropriation of our material, there doesn’t seem to be much that we can do about it beyond grousing in the columns of movie critics, when we get the chance.”

Q. A recent news item reports: “Violence, sex and profanity in movies increased significantly between 1992 and 2003, while ratings became more lenient, according to a new Harvard study.” They seem to be examining two related phenomena (lax ratings and graphic content).

I see two possible scenarios, the first being that movies are indeed increasing in graphic quality/quantity. The second scenario is that movie content has not changed, relatively, but instead films are not being rated appropriately (i.e. what was appropriate for R is now OK for PG-13). I guess I’m being wary of this study’s possible politics and its underlying agenda. Do you really feel that films are becoming more violent, or do you see the increase in violence as a misperception based on a crappy ratings system? Shawne Malik, St. John’s, Newfoundland

A. There is less “real” violence (as opposed to CGI fantasy violence) in movies today than in the 1970s — and a lot less sex and nudity. At the same time, I have the subjective sense that the ratings system has become more permissive or porous. The studios put enormous pressure on the MPAA to give them ratings that maximize their audiences. The NC-17 rating was the first victim, and now the studios are avoiding the R.

I agree with the Harvard study that there is now more violence and profanity in PG-13 movies. A long-term result of this trend may be a loss of serious content for adults, as more movies position themselves for the desirable teenage boy market.

Q. Your column noted that Columbia TriStar says its upcoming “Three Stooges” DVDs will be released in color and black and white, with the intention to “broaden the appeal of classic black and white films and introduce them to a new generation of viewers.”

The obvious implication there is that classic b&w films do not appeal to the average viewer of today’s younger generations. I’m in my late 30s and enjoy older films, but find myself in a minority among those within my age group. My parents are in their late 50s. It would appear as though those who are in that age range constitute the last generation of movie watchers to have a sincere desire to watch older b&w films, or older color ones for that matter.

In the next 20 to 25 years, do you believe, with the exception of select films such as “The Wizard of Oz” and “Casablanca,” that we will be facing the virtual extinction of old classic films? With money being the bottom line for studios, video release companies, etc., and with the likely decline in the demand for these older movies, will scrounging around for used VHS/DVDs on eBay be the primary avenue for the classic movie fan of the future to find and watch these great films? Tim Dubois, Bedford, Texas

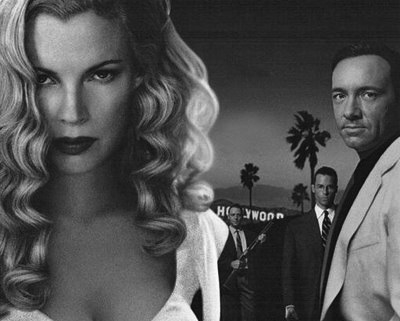

A. There will always be those who love old movies. I meet teenagers who are astonishingly well-informed about the classics. But you are right that many moviegoers and video viewers say they do not “like” black and white films. In my opinion, they are cutting themselves off from much of the mystery and beauty of the movies.

Black and white is an artistic choice, a medium that has strengths and traditions, especially in its use of light and shadow. Moviegoers of course have the right to dislike b&w, but it is not something they should be proud of. It reveals them, frankly, as cinematically illiterate.

I have been described as a snob on this issue. But snobs exclude; they do not include. To exclude b&w from your choices is an admission that you have a closed mind, a limited imagination, or are lacking in taste.