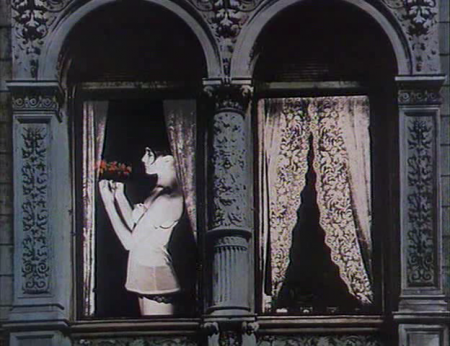

Poland-born director Walerian Borowczyk’s cinema is neither

decorative not decorous. In both his animated and live-action films, he favors

plainly-composed head-on shots, mostly medium in length. His lighting is

generally flat. Although he concocts startling images, he very rarely makes

pretty ones. Even in a film set in 13th-century France, he favors

cinema language that is almost pedestrian. And yet every one of his films—his

career extended from the mid-‘40s until the early ‘90s, and he died in

2006—startle in some way.

Arrow, the exceptionally adventurous video label from

England, shows both considerable skill and considerable daring in its limited

edition “Boro Box,” a dual-format, multi-disc set that collects five of

Borowczyk’s features and 15 of his shorts (both animated and live-action) and

also includes an exhaustive book of biography and criticism, which, turned

over, reveals another book of the filmmaker’s short stories and drawings. It’s

a head-spinning crash course in the works of a filmmaker who’s not easy to

like—he’s not nearly as intellectually adroit or witty as, say Luis Buñuel, to

name a cinematic provocateur who was a major influence on Borowczyk—but whose

ability to appall and exhilarate and to make one fall sideways laughing at

erotic absurdity will certainly find appreciation from anyone whose taste for

the Psychotronic runs to extremes.

Margolit Fox, in her 2006 New York Times obituary, wrote of

Borowczyk that he was “described variously by critics as a genius, a

pornographer and a genius who also happened to be a pornographer.” The problem

with this assessment is that even at its most sexually explicit, and be warned,

the work could get very sexually explicit indeed, Borowczyk never betrays a

desire to arouse. His most notorious film, 1975’s “The Beast,” included in this

set, opens with a scene of unsimulated horse-mating, and ends with a dream

sequence in which a maiden is ravished, in a variety of ways and positions, by

a man-beast with a massive and rather silly-looking tool of reproduction that

keeps spouting…well, you get the idea. I can’t imagine a human being finding

such stuff genuinely stimulating in the way that pornography itself actually

has to intend in order for it to be pornography (and no jokes about Comic-Con

attendees and their predilections, please). So if Borowczyk’s not a

pornographer, what is he?

The keys are found in the early work collected in the Arrow

box. I won’t lie: my favorite is very first, the “Short Films And Animation,”

which contains a beautiful rendering of the 1958 short “Astronauts,” a picture

he made with the legendary Chris Marker soon after relocating to France. Like

the films of Czech director Karel Zeman, Borowczyk’s animated work provides the

delightful missing links between Melies and Terry Gilliam; “Astronauts” is a

work of whimsical subversion and freedom. Boro’s 1963

destroyed-room-reversal-and-loop 1963 masterpiece “Renaissance” anticipates The

Quay Brothers while indulging a fantastic anarchical streak, something pushed

to full throttle in his 1967 animation/live-action hybrid “Theater of Mr. and

Mrs. Kabal.” David Thomson, a critic who is nothing if not discriminating,

pronounced Borowczyk “one of the major

artists of modern cinema” strictly on the strength of these works. He’s not

wrong. Power relations, both political and sexual, are the subjects of his two

live-action features collected here, 1968’s grim and grimly funny totalitarian

allegory “Goto: Isle Of Love” and the 13th-Century tale of amorous

machinations in a French court, 1971’s “Blanche.”

It gets tougher, though, to suss out what Boro is on about

as the work gets more explicit. Various accounts of the filmmaker find him, in

a fashion not unreminiscent of the career travails of rough-hewn erotic

fantasist Jean Rollin, making a kind of Faustian bargain with sex-content

hungry European film producers in an effort to realize a vision. But as out

there as the content of “Immoral Tales” gets (Paloma Picasso’s Elizabeth De

Bathory really does take a rejuvenating bath in the blood of slaughtered

maidens, and a comely Borgia has sex with an uncle, who happens to be the

gosh-darn Pope), there’s something about its cinematic detachment that makes me

either uncomfortable or indifferent, I can’t say which. As for “The Beast.”

Well, as I mentioned before, it opens with an explicit scene of horses mating.

To which I say, “ew,” but after saying that, I think, why I should be

mortified, let alone be mortified by the prospect of potential mortification on

the part of you, the reader, when, after all, a much-respected film like

Bertolucci’s “1900” opens its second half with unsimulated footage of a live

pig’s transformation into sausage, and few critics or viewers go to the

fainting couch over that? This is a distinction worth thinking about, so why do

I resent “The Beast” for compelling me to think about it? Borowczyk’s key strength as a filmmaker could

be his desire to show us things we don’t want to see, and to show them in the

plainest light. The perversions on display in “The Beast” have a laughable

dimension to them, but its evocation of a sexuality whose exhaustion brings

death speaks to some of civilization’s most enduring hang-ups.

This is hardly the only question brought up by the material

in this incredible set, which features nothing but beautifully rendered

transfers, terrifically stimulating and exhaustive extras, and superb critical

texts. As much as some of the stuff here irritates and frustrates me, it’s made

me even more curious than I once was about the rest of Borowczyk’s work. I’m

pleased, then, to learn that Arrow’s not through with its exploration of the

filmmaker yet, and will release his 1982 “Docteur Jekyll et les femmes” in

2015.