Before watching Netflix’s five-part docuseries, “The Confession Killer,” my knowledge of Henry Lee Lucas was relatively limited. Like a lot of movie fans, I had seen the excellent “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer,” which is loosely based on the crimes of Lucas and his buddy Ottis Toole. And I knew vaguely that Lucas was one of those boastful sociopaths who took credit for crimes he probably never committed. Monsters have a way of enhancing their bad behavior when they’re in the spotlight. If you’re already going away for a dozen murders, what’s a dozen more? Especially if it gets you headlines, interviews, and accolades from the authorities for “doing the right thing”? What “The Confession Killer” reveals is much darker and more devastating than I realized. A man once accused of being our most prolific serial killer likely is nowhere close to that, and the crimes he confessed to and the cases closed because of his confessions had nothing to do with him. And what’s even worse is that people who knew better enabled his false confessions, leading to murderers running free.

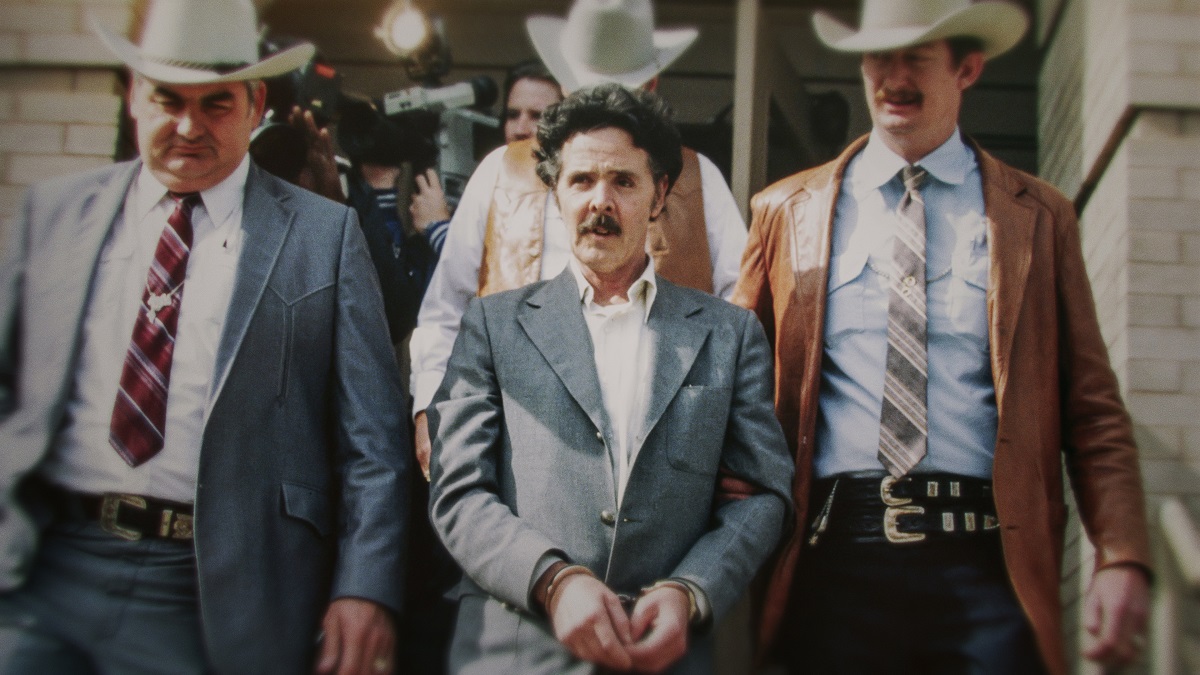

Oscar nominee Robert Kenner (“Food, Inc.”) directs the series, which uses a lot of interviews with major players and archival footage of Lucas, who died in prison in 2001. In 1960, living in Michigan, Lucas killed his mother. He served time for that, and was released in 1975, when he befriended Toole, and became a drifter. He ended up in California with his 15-year-old niece, the two of them working for an infirm woman named Kate Rich. The general consensus is that Lucas actually did murder both of them, and he confessed to doing so when he was picked up in 1983. And then he didn’t stop confessing.

According to Lucas, he had spent the last few years roaming the country with Toole and committing random murders. At first, his stories made sense, and the authorities were so eager to close cases that they established the Lucas Task Force. He gave them details he shouldn’t have known if he wasn’t the killer, and over 200 cases were cleared. No one bothered to corroborate if Lucas was actually in the cities in which these crimes were committed or how he could travel cross-country and commit one crime on the West Coast on Tuesday and another on the East Coast on Wednesday. It took family members and private investigators to raise the right questions and reveal that all of it was a lie.

Why would a man confess to crimes he didn’t commit? Kenner reveals that such actions made Lucas a celebrity. He got preferential treatment, was the subject of documentaries, and basked in the glow of being a famous murderer. And it became clear that the authorities were feeding him the information that only the killer could have known to close their cases. He told them what they wanted to hear. And more murders were committed because the process of Lucas confessing allowed the real killers to stay on the streets. As the Lucas stories fell apart, authorities dug in their heels, refusing to believe they didn’t have the right guy. There are some in the doc who still won’t admit it.

Crime documentaries about serial killers are common—there’s a whole network devoted to them—but “The Confession Killer” tells a uniquely disturbing story of how good people could make tragic mistakes, give grieving parents false hope for justice, and enable a sociopath with a low IQ to enjoy his 15 minutes of fame. It’s well-constructed and a quick watch, the kind of thing that fans of “The Keepers,” “The Staircase,” and other Netflix true crime hits should eat up this holiday season.

Whole series screened for review.