“Hey, Boo: Harper Lee & To Kill a Mockingbird” (82 minutes) premieres on the PBS series “American Masters” on Monday, April 2nd, at 10 p.m. (check local listings). The film is also available on-demand via Netflix and iTunes.

To Kill a Mockingbird was published on July 11th, 1960, and Harper Lee’s first and only novel has been a publishing phenomenon ever since. Although its first printing by the venerable publishing house of J.B. Lippincott was a mere 5,000 copies, it was an immediate bestseller, and has consistently sold a million copies a year for over 50 years. It was a shoo-in for the Pulitzer Prize, and is frequently cited as the second-most beloved book of all time, after the Holy Bible. Some British librarians went a step further: In a 2006 poll, they ranked Mockingbird at the top, above the Bible, in a list of books “every adult should read before they die.” Despite some early objections to its use of racial epithets (specifically the “N-word”), the novel has been required, if sometimes controversial, classroom reading for decades.

With its potent themes of racial injustice, inequality, courage, compassion and lost innocence in the noxiously segregated American South, Lee’s novel preceded and fueled the civil rights movement that erupted in its wake. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that To Kill a Mockingbird is the most influential novel of the 20th century, considered by many to be America’s national novel. The equally beloved, Oscar-winning 1962 film version — famously adapted by Horton Foote and directed by Robert Mulligan — was immediately embraced as an enduring classic worthy of its source material.

It seems perfectly in character that Nelle Harper Lee hasn’t given a full interview since March of 1964. How could anyone blame her for avoiding the public feeding-frenzy that accompanies phenomenal success in America? Lee, who dropped “Nelle” from her name for the purposes of authorship, was only 34 when Mockingbird was published, and after an initial flurry of interviews and public appearances, she never felt obligated to play the fame game. Unlike her childhood friend Truman Capote, she shunned celebrity, believing that authors should preserve their anonymity and let their work speak for itself. Now 85, Lee is no recluse; she still travels between New York and her hometown of Monroeville, Alabama, and over the years she’s made occasional public appearances to accept awards or Presidential honors. Aside from a few essays published many years ago, Lee’s only public writing was a letter (ironically, about writing) published in Oprah Winfrey‘s “O“ magazine in 2006.

Taped excerpts from that final 1964 interview (for New York radio station WQXR) add special substance to the affectionate documentary, “Hey, Boo: Harper Lee & To Kill a Mockingbird,” but the film’s writer, director and producer, Mary McDonagh Murphy, turned Lee’s subsequent silence to her advantage. Rather than make a strictly biographical film about the author, Murphy (who also wrote a companion book, Scout, Atticus and Boo: A Celebration of To Kill a Mockingbird) has by necessity crafted an eloquent, evocative biography of the book itself. Add to this approach on-screen interviews with noted authors, long-time residents of Monroeville and rare, exclusive interviews with a few of Lee’s closest friends and family, and it’s likely that “Hey, Boo” (a reference to the novel and film’s most pivotal line of dialogue) will remain the definitive film portrait of its subject.

Those Mockingbird character names have become touchstones of American literature and, by extension, all of popular culture. “Scout,” the novel’s irresistible narrator, is a rebellious six-year-old tomboy in Maycomb, Alabama, Lee’s fictional stand-in for Depression-era Monroeville. In a feat of narrative elegance that many writers continue to praise as a miraculous achievement, Lee presents Scout as an adult narrator reflecting on her past, but the novel’s dominant perspective remains that of the scrappy, energetic scamp who, with her older brother Jem and summertime friend Dill, learns some of life’s hardest lessons when racial injustice strikes close to home in 1932. “Atticus” is, of course, Scout and Jem’s father, Atticus Finch, a still-grieving widower and small-town lawyer who agrees to defend a black man, Tom Robinson, who’s been accused of raping a young white woman, Mayella Ewell. She’s the abused daughter of Bob Ewell, a hateful drunk and bigot who is humiliated during the course of Robinson’s trial.

Then there’s Boo Radley, the novel’s ostensible “villain,” a reclusive neighbor whom the locals speak of in hushed, cautionary tones. He exists, in the vivid imaginations of Scout, Jem and Dill, as a malevolent child-stalker, shrouded in mystery. In truth he’s one of the unlikeliest heroes in all of American literature: Boo Radley is the catalyst for the novel’s most enduring lessons of compassion. In both novel and film, it is Scout who utters the words “Hey, Boo,” a child’s gesture of understanding kindness that leads To Kill a Mockingbird to its unforgettable conclusion. (In the film version, Robert Duvall made his auspicious big-screen debut as Boo, expressing the character’s deep well of humanity without uttering a word.)

Because the book and film of “To Kill a Mockingbird” have become inseparable in our collective consciousness, “Hey, Boo” chronicles the evolution of both, with emphasis on Lee and the process of writing her masterpiece. The novel’s autobiographical elements are well-known: Scout may be a reflection of the young Harper Lee (though some scholars insist that Lee shares more in common with Boo), and Dill is clearly based on Capote, who was befriended by Lee while spending childhood summers with relatives in Monroeville.

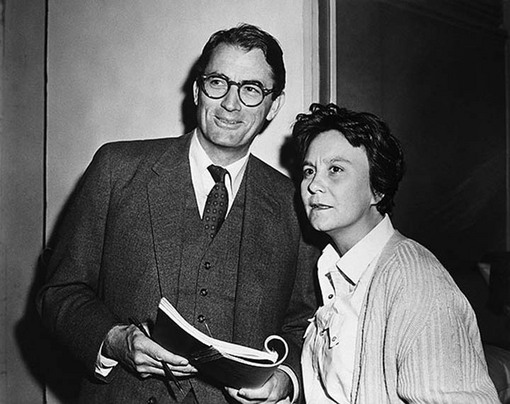

Although Lee never acknowledged it, Atticus was obviously modeled after her father, A.C. Lee, a small-town legislator, attorney, and newspaper editor who was, in fact and fiction, a paragon of virtue to his adoring daughter. Gregory Peck won an Oscar for his portrayal of Atticus in the ’62 film, and for the rest of his life he cited Atticus as his signature role. “Hey, Boo” also includes an interview with casting director “Boaty” Boatwright, who recalls how Mary Badham and Philip Alford were cast as Scout and Jem, respectively, in the course of one serendipitous casting day in Birmingham, Alabama. Like the novel before it, the film seemed to lead a charmed life from pre-production to public acclaim.

To explore the novel’s enduring legacy, Murphy recruited nearly 30 well-chosen interview subjects to share personal stories of the novel’s impact and reflect upon its importance in the context of the civil rights movement. Southern writers including Scott Turow, Rick Bragg, Adriana Trigiani and Mark Childress provide their own unique perspectives on the film’s detailed portrait of the segregated South. (Turow, for example, suggests that while men as virtuous as Atticus Finch may not actually exist, the character represents an ideal worth striving for.) Tom Brokaw, Oprah Winfrey and others are invited to read their favorite passages from the book, and it’s here that we see how Horton Foote (in his Oscar-winning screenplay adaptation) preserved much of Lee’s dialogue verbatim. (In this regard, “Hey, Boo” serves as a fine companion piece to “Fearful Symmetry,” the feature-length “making of” documentary that accompanies “To Kill a Mockingbird” on DVD and Blu-ray. In that film, Foote reveals that it was the film’s producer, Alan J. Pakula, who urged him to compress the novel’s three-year timeframe into a single year.)

Murphy’s documentary coup de grace is the inclusion of exclusive interviews with Lee’s close friends Joy and Michael Brown, and Lee’s older sister Alice Finch Lee, 99 years old at the time of filming and still working as a clerk in the Monroeville law firm founded by her father. It was the Browns who hosted Lee’s first visit to New York City in 1957 (at the behest of mutual friend Truman Capote), and it was their extraordinary generosity that allowed Lee to take a year off from her dead-end job as an airline reservations agent and focus on writing Atticus, the rough-hewn novel that would eventually become To Kill a Mockingbird.

Harper Lee now lives with her sister in Monroeville, so the interview with her older sibling represents the closest we’re ever likely to get to a latter-day Harper Lee interview. Speaking with a raspy, high-pitched drawl, Alice Finch Lee delivers the final verdict on Truman Capote: When Harper won the Pulitzer for To Kill a Mockingbird, Capote’s petty jealousy prevented him from celebrating his friend’s success, and the friendship effectively ended. Years later, a brief controversy erupted over the bogus suggestion that Capote (who did nothing to correct the misconception) actually wrote some of Mockingbird when Harper Lee accompanied him to Kansas to research the “non-fiction novel” that would become In Cold Blood (as dramatized in the 2005 film “Capote” and 2006’s “Infamous“). The rumors were unfounded, and Capote’s pathetic, drug-addled final years (he died at 59 in 1984) were spent wallowing in the hollow trappings of celebrity that Harper Lee has avoided to this day.

Aside from setting that gossip record straight, “Hey, Boo” takes the high road as a celebration of a novel that has never lost its relevance and widespread appeal. A brief sequence visits a present-day classroom where young students discuss the still-timely lessons imparted by To Kill a Mockingbird, and we also learn that the novel began as a loose-knit assembly of well-observed character studies, and was then shaped and refined over two years of rewrites and editorial input from Lee’s literary agent, Maurice Crain. Even then, the book was rejected by 10 publishers before finding a home at Lippincott.

Interesting details abound in “Hey, Boo,” like the fact that A.C. Lee gave his daughter her first typewriter (a sturdy Underwood), and that Harper has been a hunt-and-peck typist all her life. Most importantly, the film provides the most thorough and sympathetic answer to the question that has haunted Harper Lee for over 50 years: Why didn’t she write another novel? What happened to the Harper Lee who once said her ambition was to be “the Jane Austen of the American South”? Suffice it to say the reasons will be fully understood by any writer who’s faced the intimidating tyranny of a blank page. Can you blame Harper Lee for ultimately concluding that, as the author of To Kill a Mockingbird, she had nowhere to go but down?

And while Harper Lee’s sexual orientation has long been a topic of speculation, “Hey, Boo” (like Charles J. Shields’ 2006 biography of Lee), appropriately treats that question as a non-issue. What matters is the seemingly bottomless well of wisdom that To Kill a Mockingbird imparts to its readers. As Lee so famously wrote, “it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird,” because all it does is sing and bring beauty into the world. The same could be said for Lee’s one and only novel. Over 50 years and 50 million copies later, it’s a gift that keeps on giving.