“Zhou Yu’s Train” tells a pointlessly convoluted version of a love story that would really be very simple, if anyone in the movie possessed common sense. We know love is blind, but need it be obtuse? The three lovers in Sun Zhou’s new film, controversial in China for sex scenes that are more fond than fervent, make life miserable for themselves and, to a lesser degree, for us.

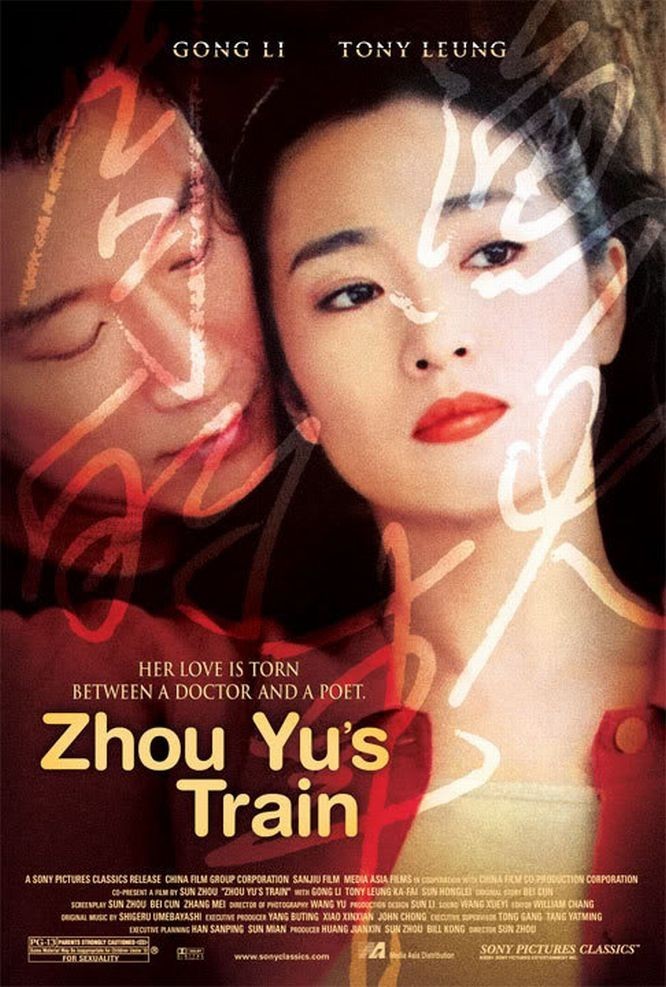

Our misery is leavened by the visual qualities of the film, which, like most recent work from China, is spectacularly good to look at. There’s also the central presence of the Chinese superstar Gong Li, who plays a dual role so confusingly written that it might as well be one person, but she plays it well.

Her character is a painter of porcelain pottery named Zhou Yu, who is secretive, with an active romantic imagination. A teacher and poet named Chen Qing (Tony Leung Ka Fai) falls in love with her, and gives her a poem comparing her to a mystical lake named Xan Hu. That this poem to her also appears in the district newspaper makes a deep impression, and soon she is taking a long train ride twice a week from her city to his.

The movie backs into this straightforward narrative by beginning in the middle of one of the journeys, as a veterinarian named Zhang Qiang (Honglei Sun) flirts with her and asks to buy the painted porcelain vase she is taking as a present to Chen Qing. Zhang is so insistent that she finally ends the conversation with a bold dramatic gesture. She dislikes Zhang as much as she loves Chen Qing — she thinks.

But Chen Qing is a case rewarding further study. He seems to be a squatter in a kind of forgotten library, where his simple bachelor existence suits him well. He is happy enough to make love two afternoons a week, but a little frightened of Zhou Yu’s fervor. Mention is made of a teaching position he could take in Tibet.

It occurs to us, long before it occurs to Zhou Yu, that the vet would make a better partner than the poet. This would be even more obvious if the film weren’t needlessly fragmented, so that we jump around in time and have to piece together the actual chronology of her relationships with the two men. The vet at one point actually follows her on one of her train journeys, discovering a secret about Chen Qing that is well known to Zhou Yu but will not be mentioned here.

In my notes, I wrote: “Who is the short-haired girl? Looks like Gong Li.” Reader, it was Gong Li, in the dual role, playing a character named Xiu. She is apparently a former lover of Chen Qing’s who is now a narrator telling us about his affair with Zhou. All very well, except by casting the same actress the movie led me to assume I was seeing Zhou herself at two stages of her life, or at least at two stages of her hair-styling history. Xiu works mostly as an unnecessary diversion.

The qualities of the movie come during small, well-observed moments. Zhou covering her lover’s face with hungry kisses. The train conductor reminding the vet, “That’s the same girl who fainted one day, and you refused to treat her.” The vet pointing out he has been trained to work with animals. Above all, the loneliness of the long-distance journeys, which seem to take on an existence of their own, as if Zhou prefers faithfully traveling to and from her lover to actually being with him, or apart from him.

The film is impeccably photographed, and the characters become convincing as themselves, if not always in their relationships. The story, once the complex telling is unraveled, invests these people with more romantic significance than they deserve.

And if it is true, as I suspect, that Zhou Yu’s train journeys have an importance for her apart from their alleged purpose — if, to put it simply, she just plain likes to take the train — the movie could have been a little more amused, and amusing, about that. Does she get frequent traveler miles?