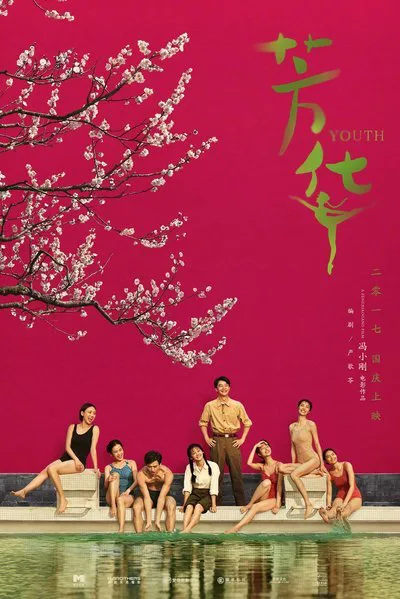

The story behind the Chinese government-delayed (and probably censored) international release of the frustrating romantic drama “Youth” made me dislike the film’s toothless sentimentality and historical revisionism even more. This is a movie about three soldiers, all of whom perform or serve in the People’s Liberation Army during the mid-’70s, just before and after the death of Zeong Mao. Unfortunately, the makers of “Youth” fail to meaningfully address the time period that informs its protagonists’ fraught relationships. In fact, the filmmakers over-extend themselves to solicit empathy for their doomed protagonists. “Youth” is so unbearably nice that I eventually wished it were remade by misanthropes. That the makers of “Youth” don’t even indirectly acknowledge the way that nationalism, like faith in Santa Claus or the New York Mets, will inevitably break your heart is especially disappointing, given how poorly the Chinese government treated director Xiaogang Feng and his film.

Some background: in late September, the Chinese film bureau shelved “Youth.” This was about a week before the film’s planned U.S. theatrical release. “Youth” had already screened at the Toronto International Film Festival earlier that month. But the film’s late September U.S. release was cancelled without an official explanation or promise of future playdates. Feng (“The Banquet,” “Assembly”), a filmmaker whose popular melodramas have earned him a reputation as “China’s Spielberg,” promised to comply with the government’s film bureau in making any necessary changes.

Variety’s Peter Frater speculates that the film’s release was postponed to avoid potential embarrassment given the closeness of the film’s release to the National Party Congress, a closed-door election that occurs once every five years. This reading makes sense given that the National Congress is, according to CNN, “the biggest and most-watched event in the Chinese political calendar,” partly because it resulted in the re-election of President Jingping Xi for his second five-year term as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, the highest rank in the Chinese government. (Note: “President” is technically a secondary role, traditionally held by the General Secretary).

These real-life happenings make it harder to appreciate Feng’s characteristic focus on doomed lovers who just happen to live through extraordinary times. The story’s narrator, Suizi (Chuxi Zhong), even hastily starts her prefatory voice-over narration by saying that she is not the subject of this story. Instead, she selflessly focuses on the hard-luck dancer Xiaoping (Miao Miao) and the square-jawed soldier Feng Liu (Xuan Huang). Suizi’s perspective is generally free of editorializing or subjective flourishes. In fact, her personality is so deeply steeped into the film’s narrative that it’s often easy to forget that “Youth” is told from a third party’s point-of-view.

This is ironic since Xiaoping and Liu’s near-miss romance either lives or dies based on the force of their respective convictions. Spurred on by a desperate home life, she throws herself into her role as a dancer in the PLA’s touring arts troupe until about 1976, the year of Chairman Zedong Mao’s death. But as Suizi warns viewers during her introduction, Xiaoping never fits in with the other dancers. Still, Liu, a well-regarded community leader, responds to Xiaoping’s unflagging idealism. Unfortunately, he soon proves to be not as upstanding as his reputation, as we see in a crucial scene where forces himself on another dancer, Dingding (Caiyu Yang). Xiaoping’s attraction to Liu understandably flags after that, and so does her conviction.

The gentle nature of screenwriter Geling Yan’s plot, based on her biographical novel, is upsetting because it thoughtlessly repeats one of the most common war story cop-outs: war isn’t hell because countries, institutions and military organizations are corrupt, but because, uh, stuff happens, and life’s not fair. Feng never bursts Xiaoping’s bubble by suggesting that being part of the arts troupe and instilling patriotism in fellow soldiers is potentially dangerous. Instead, we’re treated to spectacular group renditions of military songs and precise dance numbers. These scenes suggest that “Youth” might have been a great “putting on a show”-style musical. But instead, the film only confirms the seamlessness of ideology by primarily focusing on its sheen, and then showing how its individual proponents grow bitter over time and ultimately fall apart. Here, ideology doesn’t kill people, the indifferent passage of time does.

That fatalistically passive philosophy is infuriating when you watch a critical battle scene that takes place during the Sino-Vietnam border conflicts of the ’80s. This scene was, at one point, rumored to be the real reason that the film’s release was delayed. But who could object to such an empty-headed and emotionally uninvolving set piece? The camera sweeps around the battle field, darting past exploding meat puppets, floating over tanks, finally settling on an eye-roll-inducing scene of two soldiers, one vainly trying to pull the other out of a quicksand-like sinkhole. Feng lingers on the two men’s hands as they clutch at each other. It’s a precious but empty moment because we have no idea who these guys are.

I only have myself to blame for hoping that Feng would make a movie that acknowledges, or in some way critiques, the government that effectively allows and enables him to make popular historical fiction. What did I really expect from a filmmaker whose previous films are all so … well, mild? Even the romantic-comedy “If You Are the One” and its uneven sequel are as forceful as a peck on the cheek. Nevertheless, I did expect more from “Youth,” especially given that this was the year that the Chinese box office was predicted to surpass that of North America’s. China’s biggest film this year, and of all time, is “Wolf Warrior II,” an ugly, jingoistic action film. “Youth” isn’t much more satisfying. If you’re looking for a thoughtful, energizing Chinese historical drama from this year, I highly recommend Ann Hui’s “Our Time Will Come.” As for Feng’s latest: while “Youth” should not be avoided, it will probably break your heart in all the wrong ways.