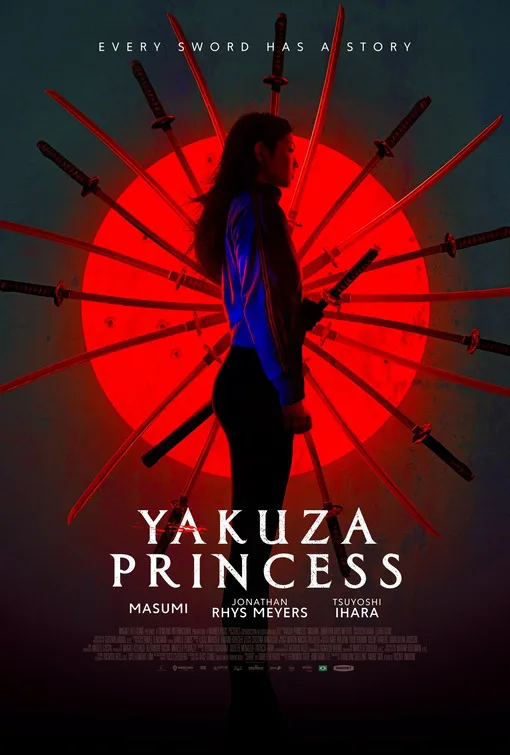

The generic action flick “Yakuza Princess” starts with a bold declaration of intent: an on-screen text tells us that we’re now in São Paulo, Brazil, specifically a neighborhood that hosts “the largest Japanese community in the world.” That attention-grabbing statement promises a level of authenticity—or maybe cultural specificity—that the ensuing movie, about the heiress to a vast yakuza crime empire, does not deliver.

“Yakuza Princess” often devolves into the sort of clichés and stereotypes that would make American comic book writers of the 1970s blush, because these tropes were already tacky when they were previously ripped off from the many Japanese yakuza dramas of that period. And yet, “Yakuza Princess” is based on Samurai Shiro, a recent comic book, and it still features a lot of jive about the bygone era of chivalry and honor.

Two protagonists seek information about their respective pasts: Akemi (Masumi) wants to learn more about her grandfather, a now-dead crime boss; and Shiro (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) is an amnesiac with a sword. These two stories eventually come together, but only after Akemi and Shiro meet up, discover that Shiro’s sword belonged to Akemi’s grandfather, and also learn of a decent-sized conspiracy to find and kill Akemi. The Japanese mob is at war with itself in São Paulo, though it’s often hard to understand why there and why now based solely on “Yakuza Princess.”

Most of Akemi and Shiro’s respective stories feels like hand-me-downs after decades of movies and comic books about the legendary yakuza, a shadowy organization that most of us only know from pulp fiction. Byronic tattooed gangsters have become a generic type over the years, to the point where you can only tell so much about a movie that defines itself with dialogue like “In the age of the samurai, honor was everything. Unlike today.”

Shiro seems surprised, but not displeased to be part of this macho lineage, though he doesn’t say as much with his words (he’s practically a mute). He mostly floats around, and helps Akemi get in touch with his sword, which is really her sword, and was also designed by the legendary swordsmith Muramasa. Later, we are told that each Muramasa sword “has a demon lurking within.” Akemi doesn’t seem to care about that, or anything, really, except learning more about her pop-pop.

The answers that Akemi seeks are mostly found during somber chats with jaded gangsters, all of whom speak about the past like it was, in fact, a different time. Shiro gets a brief history lesson from two older gentlemen who happen to be watching video footage of a third guy committing seppuku, an act of ritualized suicide. “His clan was decimated,” according to the first gentleman. “This is the only way he can preserve his honor,” says the second. A few other supporting characters also walk and talk like this, especially petty villain Kojiro (Eijiro Ozaki), who wants whatever Akemi has, and world-weary antihero Takeshi (Tsuyoshi Ihara), who has pride, but is also tired. “You’ll never know what it’s like to die with honor,” Takeshi says. “Time of honor is over,” yells Kojiro. Rather, now is the “time of death.”

Most scenes in “Yakuza Princess” look cheap, despite some consummately moody lighting and brassy-looking silver-blue camera filters. There’s a lot of walking and talking, but this thing never really moves fast enough, not even during its action scenes. Speaking of: there are only a few worthwhile set pieces in “Yakuza Princess” since more punches are pulled than thrown, and it’s generally kind of hard to see, let alone appreciate the fighters’ synchronized movements. One fight stands out, the one where Takeshi and Akemi fend off a pair of martial artists wearing Bruce Lee yellow jumpsuits. These guys presumably wanted to show off their moves, so this brawl is a little more coherent, and a little less frantic than usual.

The rest of “Yakuza Princess” isn’t as thrilling. Feet are dragged, throats are cleared, and some blood is spilled, though only after some more goofy dialogue like “The katana has found you. You and it are one now, as you are meant to be. Go, now. Your life depends on it.” I don’t know what the Japanese residents of São Paulo are like, but “Yakuza Princess” suggests they aren’t very particular.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.