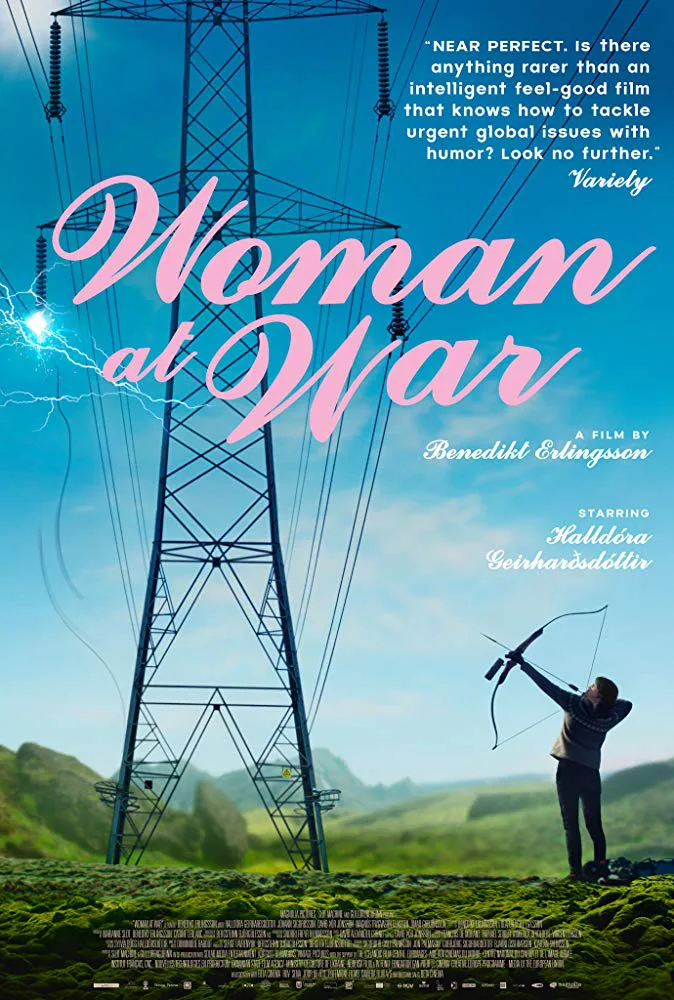

A thoughtful and dynamic blend of genres, Benedikt Erlingsson’s contemporary environmental fable “Woman At War” continually thrills with a side of laughs. In its most endearing moments, Erlingsson’s idiosyncratic sophomore feature is as rebellious and confident as the main heroine it follows through vast and damp Icelandic landscapes. She is Halla (the defiant Halldóra Geirharðsdóttir, excelling in a physically demanding role), a beloved, single choir director in her early fifties, living a secret double-life as a green activist when no one is looking. Cutting power lines to sabotage a local aluminum plant in her spare time, Halla mostly operates alone in her heroic yet elaborate quests. In the film’s breathtaking opening sequence, shot and edited in the heart-pounding tradition of cat-and-mouse thrillers (by Bergsteinn Björgúlfsson and David Alexander Corno, respectively), she runs from helicopters and drones, hides in natural cracks of the earth and finds refuge in the home of a local greenhouse farmer (Jón Jóhannsson), who lends her a runaway vehicle and becomes her unofficial accomplice.

Having no interest in making a straightforward genre film, Erlingsson doesn’t stop at creating anxiety-inducing tension and braids in an eccentric musical detail to his unique package. A fourth-wall-breaking live band (that includes composer Davíð Þór Jónsson, musicians Magnús Trygvason Eliasen and Ómar Guðjónsson on keys, drums and sousaphone) and later on, a Ukrainian a cappella trio, accompany Halla in almost every scene to both comedic and unsettling effect. Slowly, we get to know this well-intentioned and modestly equipped crusader more intimately. Living in a handsomely appointed home where pictures of Nelson Mandela and Gandhi decorate her workspace, Halla rides her bike to work, wears a congenial smile and leads a responsible life … that is of course when she isn’t climbing up rooftops and dropping exposé leaflets to help turn civic opinion against the government’s evil ecological plans. Given the nickname “Mountain Woman” by the media, Halla slowly finds herself at life-threatening odds with the authorities and their intensifying efforts to hunt her down. And this couldn’t be happening at a more inconvenient time for her—all of a sudden, her long-awaited child adoption plans start looking like a real possibility, after the adoption agency finds her an orphaned little girl in the Ukraine.

More accessible than (but just as wildly unique and pastoral as) Erlingsson’s debut feature “Of Horses and Men,” “Woman at War” strikes a near perfect balance between delivering a character study, an urgent environmental and societal message and some good old-fashioned entertainment through a genuine and warm tale of one woman’s stubborn efforts to be on the right side of history. While co-writers Ólafur Egilsson and Benedikt Erlingsson unmistakably align their sympathies with Halla, they are also critical of her privileged attitude that threatens both her future adoptive daughter’s prospects and the freedom of a random Spanish tourist (Juan Camillo Roman Estrada), who quickly becomes a prime terrorism suspect in the eyes of the police. The scribe duo deliciously twists the affairs at every turn, especially when Halla’s New Age-y twin sister Àsa (also played by Geirharðsdóttir, again with perfection) and choir singer/governmental worker Baldvin (Jörundur Ragnarsson) enter the picture as dubious partners in crime.

Cinematically and philosophically rewarding from start to finish, “Woman At War” thrives on the shoulders of Geirharðsdóttir, who brings to life two distinct characters that unite through sisterly bonds. Aspirational, feel-good but never shallow, Erlingsson’s film melds together smarts and wry humor just as neatly as it does various musical genres. The delightful combination of these elements inform and deepen Halla’s journey as a single woman, friendly neighbor and concerned citizen looking for a place in a deteriorating world she desperately tries to better. Erlingsson finds a lot of joy in her rousing, perilous disobedience. And frankly, his enthusiasm for Halla proves to be infectious.