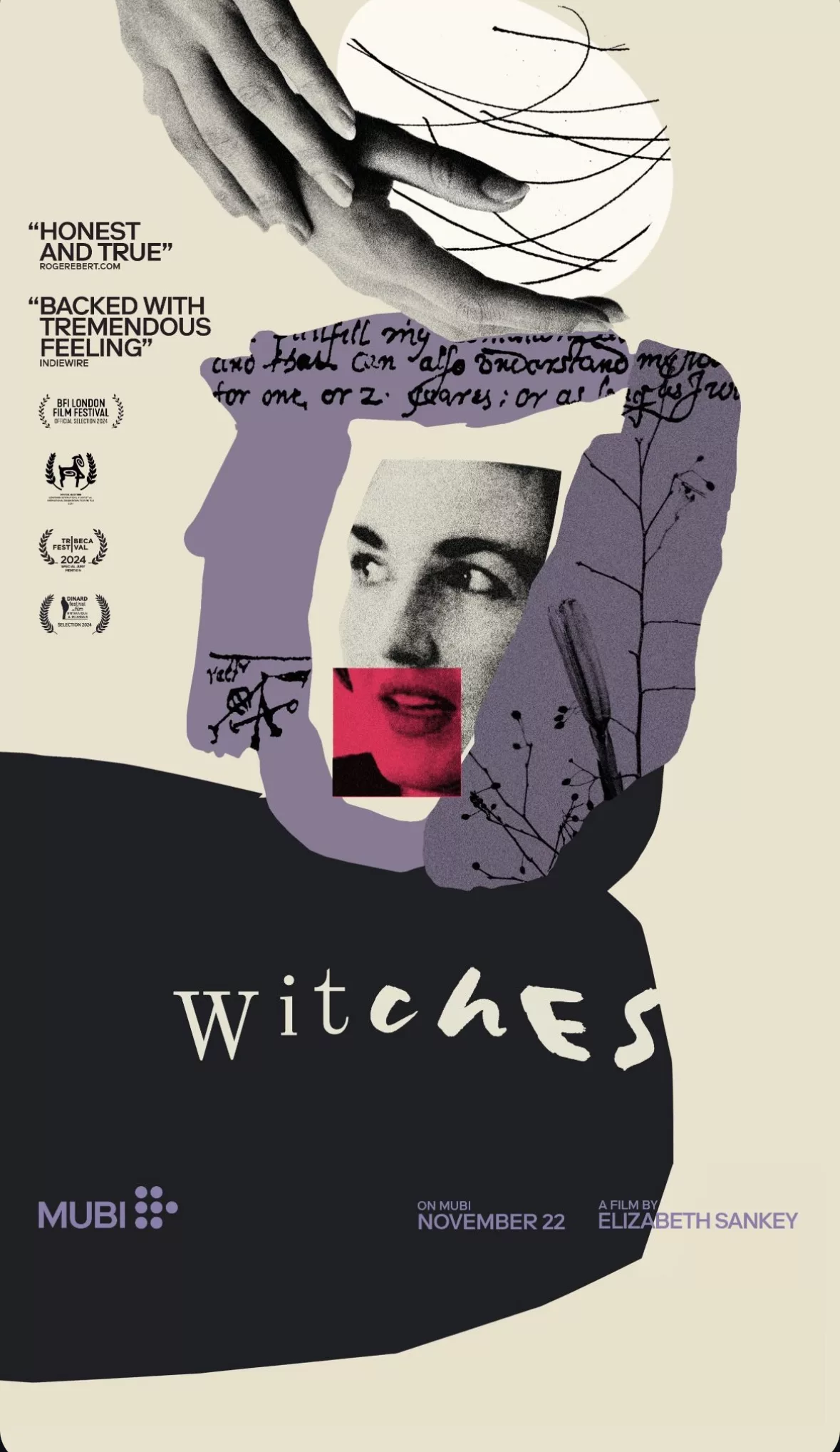

“The personal is political” has been not just a slogan but a rallying cry for feminist activism since the 1960s. “Witches,” written and directed by documentarian Elizabeth Sankey, is deeply personal and passionately political. She uses her story to illustrate, comment on, and provoke policy and cultural conversations about the expectations of mothers and the shame and guilt women feel from failing to meet those un-meetable standards. She uses examples of witches, both real-life stories of women accused of witchcraft and portrayals of witches on television and movies, to put mental illness in the context of societal fear of women’s power. Sankey’s film addresses the issue of women’s mental health from individual to societal, from medical to metaphor, clinical to cultural. The kaleidoscope of archival clips is intriguing, except when it gets distracting. The political arguments are provocative. The part you will remember, though, is Sankey’s story of her experience with post-partum psychosis, as personal as it gets.

“When you think of witches, is this what you see?” Sankey asks us, as clips from “The Craft,” “Practical Magic,” “The Witches of Eastwick,” and other well-known images flash on the screen. My first reaction: cinematic depictions of females with magical powers often require messy hair. It is a quickly recognizable symbol of a woman’s behavior being out of control, perhaps self-control, but more likely uncontrollable by society, meaning the patriarchy. The happy endings often have the women smilingly giving up their power. We see a clip from the 1942 film “I Married a Witch,” with Veronica Lake proudly telling an off-screen Fredric March that she lit the fire all by herself without resorting to witchcraft. Like “Bewitched,” the 1960s television series that drew inspiration from “I Married a Witch” and 1958’s “Bell Book and Candle,” the “happy” ending is the witch foregoing her powers to live like an “ordinary” human wife.

Sankey began experiencing symptoms of disordered thinking after her son was born. They included terrifying intrusive fears that she would harm her baby. She ended up in a psychiatric hospital–with the baby. As we learn, an essential part of the treatment she received was that the patients bring their babies with them. At first, they are watched 24/7. As they improve, they are allowed to be alone with the babies and then to go home for a few hours, then overnight. Keeping the babies with the mothers enables them to bond and also reassures them that they are capable of keeping the babies safe. This is combined with medication and therapy.

But Sankey tells us that talking with other mothers who had the same experience made the most significant and transformational difference. A key point made throughout the film is the difference between postpartum psychosis and mental illness with overlapping symptoms like hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, and obsessive worry. Psychosis after childbirth comes on much more quickly and intensely, partly because of the hormonal changes and exhaustion of new motherhood. They may also delay getting help because they fear being considered incurably unfit and having their babies taken away. Sankey puts it in the context of the fear and shame of experiencing disordered thinking at a time society tells us is supposed to be all about blissful baby love.

We can almost feel Sankey’s relief when she brings in the women who experienced what she did and gave her the support she believes was her turning point toward health. They are reassuringly recovered and warm, encouraging, and candid about their experiences. One, herself a doctor specializing in postpartum mental disorders, tells us that even when she diagnosed her own disordered thinking, the medical specialists did not believe her. While Sankey is grateful for the advances in the UK following a widely publicized story of a mother who killed herself and her baby, she makes it clear that only an open conversation about the experiences of women like those she interviews will bring about more changes that are still needed.

Sankey wants us to see postpartum psychosis through the lens of larger issues of societal expectations and restrictions. A historian tells us about the English witch trials from the 15-18th century. The trials we often only ten minutes long. Why did so many of the women “confess?” Sankey suggests that they may have been suffering some form of postpartum psychosis, concluding that the death penalty would be the only way to keep their babies safe. The personal is political, but in this film that case is made more powerfully with the personal story than the flurry of clips or the theories about history.