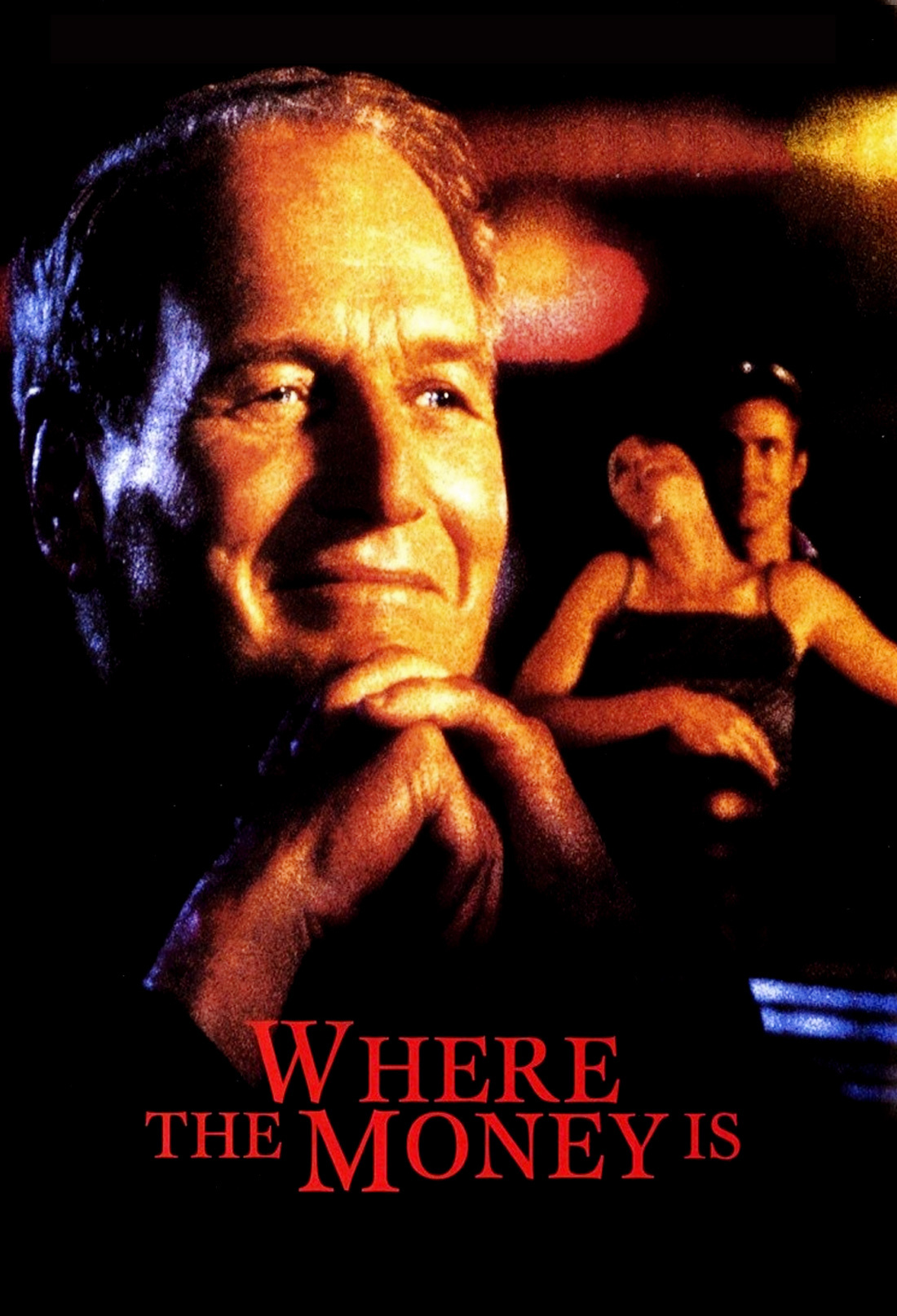

“Where the Money Is” has a preposterous plot, but it’s not about a plot, it’s about acting. It’s about how Paul Newman at 75 is still cool, sleek and utterly self-confident, and about how Linda Fiorentino’s low, calm voice sneaks in under his cover and challenges him in places he is glad to be reminded of. Watching these two working together is like watching a couple of thoroughbreds going around a track. You know they’ll end up back where they started and you don’t even have any money on the race, but God, what form.

Fiorentino plays a discontented nurse in a backwater town, married to the same guy (Dermot Mulroney) since high school. “We were king and queen of the prom, so it sort of made sense to get married,” she tells Newman. “When did it stop making sense?” he asks. Newman can say a line like that to a woman and convince her it never made sense, even if she didn’t know it until he asked the question.

I have given away a plot point by revealing that he speaks. In the opening scenes, he appears to be an old man paralyzed by a stroke. He can’t move his body, he can’t talk, he doesn’t even look at anything. It’s all an act: He’s a veteran bank robber who has studied yoga in order to fake stroke symptoms so he can be moved from prison to the retirement home, which he figures will be easier to escape from. Actually, it’s not such a big point to reveal, since (a) we somehow intuit that Paul Newman wouldn’t be starring in the movie if he didn’t move or speak for 90 minutes, and (b) all the TV commercials and review clips show him moving and speaking.

The old crook, named Henry, is a good actor, and fools everybody except Carol, the nurse played by Fiorentino. She notices subtle clues and tries to coax him out of his shell with a lap dance (she is dressed at the time, but in a nurse’s uniform, which is always interesting). He resists. This is good yoga. She abandons sex for more direct methods, and he’s forced to admit that he can indeed walk and talk. By later that night he’s even dancing in the local tavern with Carol and her husband, Wayne.

Carol realizes that Henry is her ticket out of town. Either he has a lot of money stashed away from all those bank jobs or he can help her steal some more. Wayne finds this thinking seriously flawed, but eventually the three of them end up as partners in an armored car heist. The heist is to the movie what Sinatra’s cigarette and drink were to his song: superfluous, but it gave him something to do with his hands.

Newman you know all about. At his age he has such sex appeal that when the husband gets jealous, we believe it. He has that shucks, ma’am grin, and then you see in his eyes the look of a man who is still driving racing cars and can find an opening at 160 mph. He counsels Wayne about an encounter with some dangerous men: “Be cool to these guys, right? Look them in the eye–but not like you’re gonna remember their faces.” Fiorentino is a special case, an actress who in the wrong movie (“What Planet Are You From?“) seems clueless, and in the right one (“After Hours,” “The Last Seduction“) can make every scene be about what she’s thinking she’d rather be doing. She is best employed playing a character who is the smartest person in the movie, which is the case this time.

As for the bank robber and his stroke: A lot of reviews are going to pair this movie with “Diamonds,” another 2000 movie involving a great movie star and a stroke. That one starred Kirk Douglas, who really did have a stroke, and has made a remarkable comeback. But the strokes in the two plots aren’t the connection–after all, one is real and one is fake, and that’s a big difference. The comparison should be between two aging but gifted stars looking for worthy projects.

“Diamonds” has a plot as dumb as a box of tofu. “Where the Money Is” has a plot marginally smarter, dialogue considerably smarter and better opportunities for the human qualities of the actors to escape from the requirements of the story. After you see this movie, you want to see Paul Newman in another one. After you see “Diamonds,” you don’t want to see another movie for a long time.