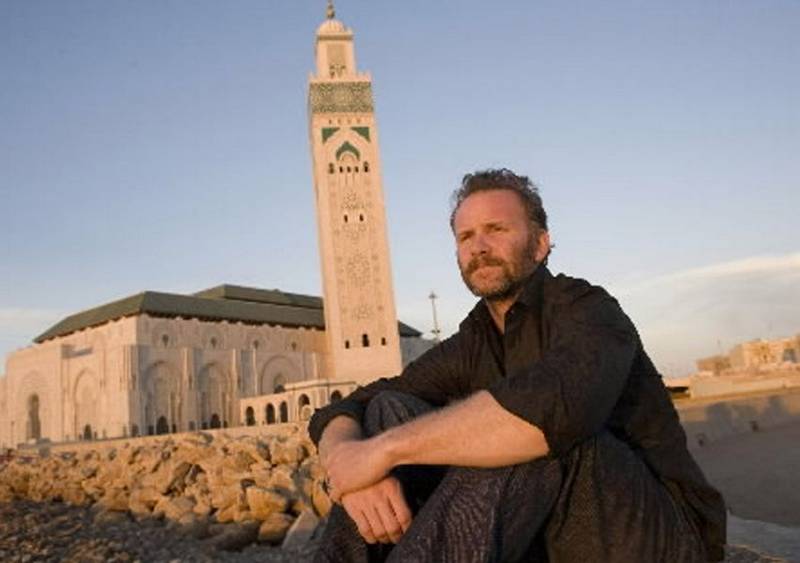

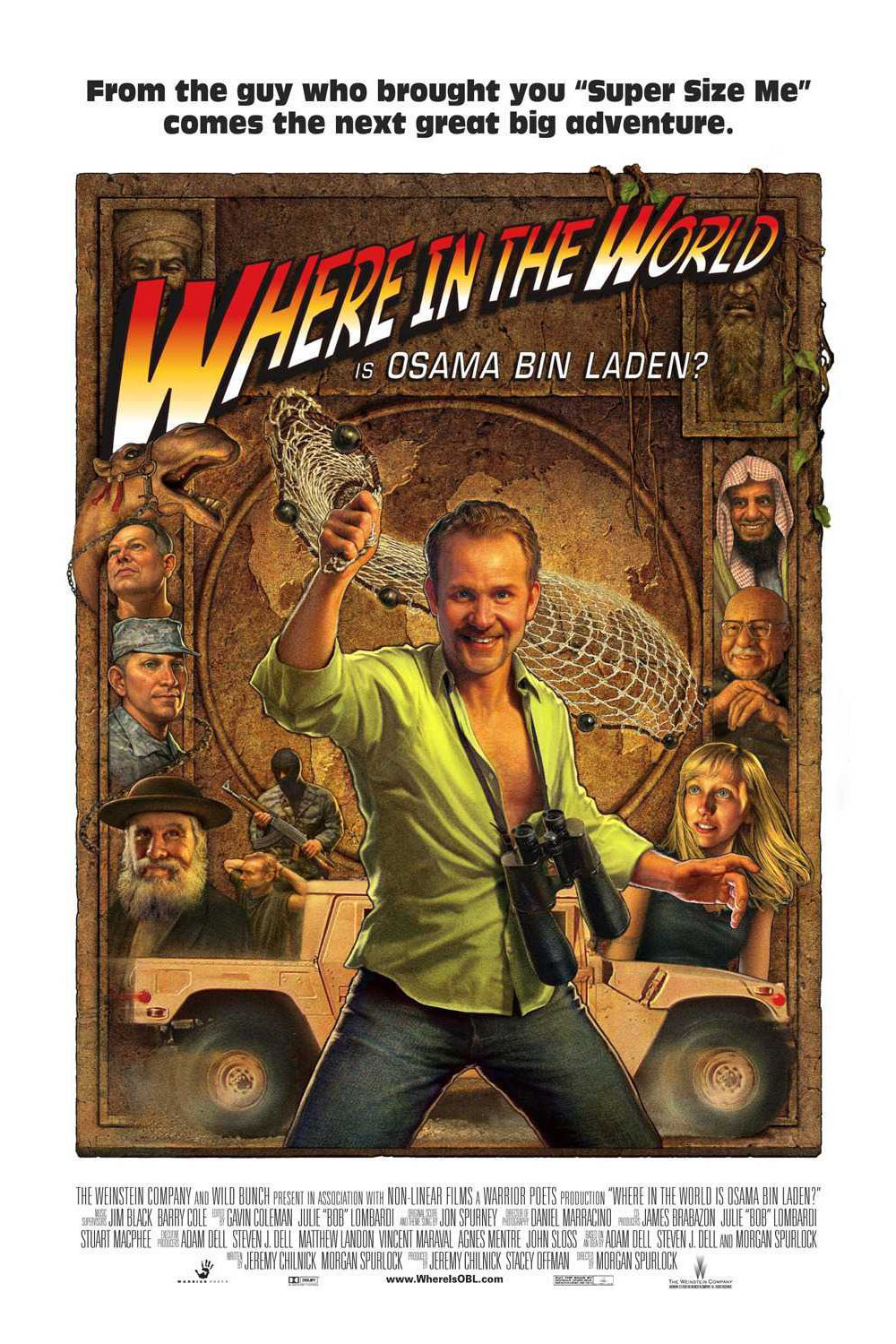

In “Big Bird Goes to the Middle East,” director and guide Morgan Spurlock takes us on a souped-up, vox-populi tour of TerrorLand, using cartoons, musical numbers and PlayStation graphics. No, it’s not really a licensed “Sesame Street” spinoff, though it plays like one (and Spurlock really does resemble Big Bird). The official title is “Where in the World Is Osama Bin Laden?” (though “Terrorism for Dummies” must have been considered) and it’s structured as a video game, with escalating international “levels” of apparent difficulty: Egypt, Palestinian Territories, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Pakistan.

A stand-up, stunt-comedy documentarian, Spurlock has been called the poor man’s Michael Moore, an assessment that’s neither fair nor accurate. His filmmaking may be comparably poor, and he does present himself as the first-person star of his essay-showcase movies, but Spurlock’s gags don’t depend on stupid, insufferably self-serving set-ups designed to place himself in a superior position to whoever’s on camera. For that reason, and because his agit-prop presentation is strictly anecdotal, Spurlock’s approach feels less smug and disingenuous than Moore’s.

In his previous film “Super-Size Me,” Spurlock performed an experiment on himself to illustrate the unhealthiness of a fast-food diet. For 30 days, he ate exclusively at McDonald’s, and the visible results were dramatic and horrifying. The premise here is that, when Spurlock’s wife becomes pregnant, the expectant father feels the need to investigate the kind of world into which their child will be born.

Employing the cliches he’s learned from American action movies about solving complex international problems through vigilantism, he decides to go it alone, against all odds, in search of the world’s most dangerous man. Just as John Rambo was deployed to win the Vietnam War many years after the fact (during the Reagan administration, appropriately), Spurlock — with tongue set firmly in cheek and head inserted deeply into posterior — sets out to track down the highest-ranking enemy commander in the War on Terror. Like Rambo, he and his film are quaintly anachronistic. When the movie shows choreographed animated Bin Ladens dancing to MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This,” you have to wonder if Spurlock thinks he’s going to be promoting his movie on “The Arsenio Hall Show.”

“Where in the World Is Osama Bin Laden?” would have worked better if it had been made back before 2001, in the years when Bin Laden posed a widely reported, universally recognized threat to world stability — realistically and symbolically — far more significant than the one he presents today. Probably nobody would have cared, least of all Condi Rice, but Bin Laden was easier to find then, and anti-American sentiment was not nearly so overt or intense.

Although the film uses trading cards to identify some of the more prominent players (not so far removed from the Most Wanted playing cards actually issued to U.S. military personnel in Iraq), Spurlock spends most of his time interviewing anonymous civilians in the manner of John Candy’s Johnny LaRue on “Street Beef.” He learns that people all over the world say they detest the arrogance of American imperialist foreign policy, but most of them think the American people themselves are OK, anyway. Again and again they say they do not hate American freedoms, they resent outside interference in their own affairs. If any of this comes as news, you may also be surprised to learn that Al Gore was never the president of the United States.

Other things Spurlock learns from people he talks to:

The threat of terrorism created the climate of fear that is being exploited by al-Qaida and the Bush administration. (That’s almost a direct quote from somebody who is not famous.)

Some terrorists are tempted by money, others are tempted by promises of paradise. (Another quote from a Moroccan fellow.)

”Everybody knows” that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will eventually end with two independent, interacting states. The question is how long it will take and how many more will die in the meantime.

The perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks intended to draw the U.S. into the Middle East, to create the perception of a war against Islam and recruit young people for a militant jihad. It worked beyond their wildest hopes. When the U.S. invaded Iraq, it opened up the country to terrorist factions from all over the region.

”In a counter-insurgency, killing the enemy doesn’t work,” notes a U.S. military officer in Afghanistan.

Spurlock’s wife is having contractions. (She tells him that herself over the phone.)

For a more illuminating examination of the symbiotic relationship between Islamic fundamentalism and American neoconservatism (a relationship based on mutually beneficial fearmongering), see the magnificent three-part BBC documentary “The Power of Nightmares.” For a more enlightening explanation of how the Bush administration bungled nearly every opportunity available after 9/11, see last year’s Oscar-nominated documentary “No End in Sight.” And for a funnier cartoon about Islamic fundamentalism (Iran in the 1970s and beyond) that’s more shaded and emotionally involving, see the film of Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel(s), “Persepolis.”

In 2008, “Where in the World Is Osama Bin Laden?” serves only as a superficial primer for people who aren’t likely to go see it in the first place.