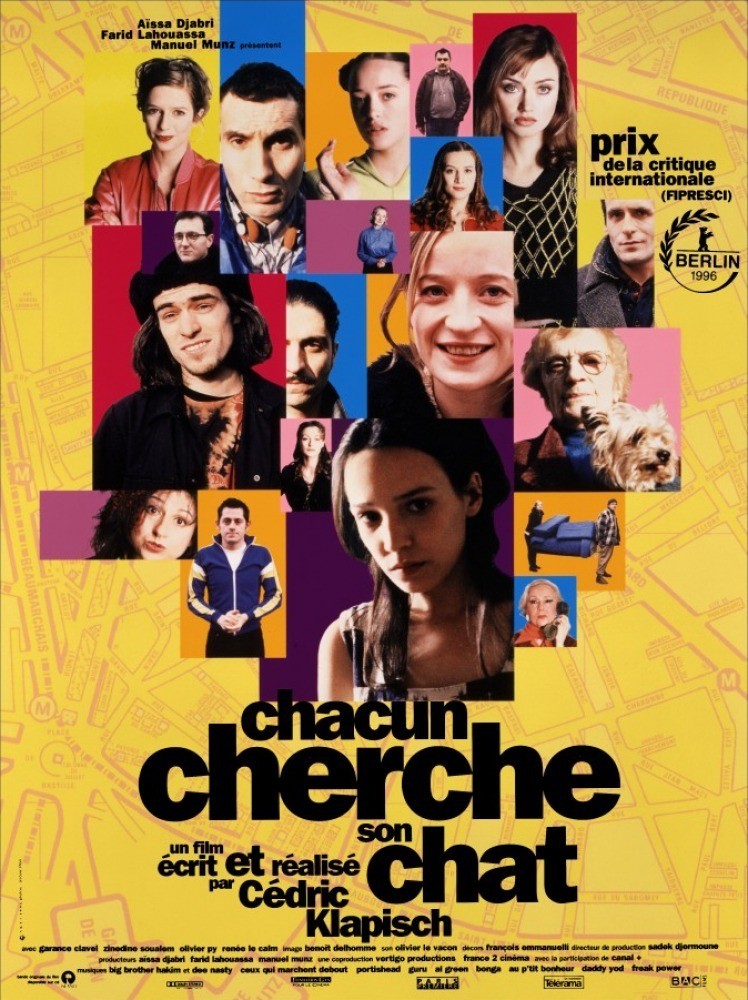

Here is a movie about a young woman named Chloe, who has no luck with men, considers herself desperately lonely, and then finds out what loneliness is when she loses her cat. She’s a little mouse, and “When the Cat’s Away” tells the story of how she plays. But it is all so much more tricky than that.

The French love to make these pictures that are about attitude and personal style. The one thing you know is that the movie is not going to be about the cat’s loss, or the cat’s return, or even the cat’s life or death. In an American movie, the heroine would think the cat’s fate was terribly important, and so would the filmmakers. But Cedric Klapisch, who wrote and directed “When the Cat’s Away,” realizes that the movie is really about a woman who has nothing better to do than obsess about her cat.

Chloe (Garance Clabel) lives in a district of Paris that was until recently rather shabby and neglected, which meant people could count on spending their lives there without being annoyed. When she decides to go on vacation, she needs someone to look after the cat (named Gris-Gris), and the waiter in the local cafe suggests Madame Renee (Renee Le Calm), an elderly cat woman who lives in a nearby apartment.

Chloe parks Gris-Gris with Madame Renee, goes on vacation (the director compresses the entire holiday into one postcard shot), and returns to find Madame Renee in distress because the cat has run away. Chloe now sets about finding the cat, aided by Madame Renee’s network of cat ladies, and by a simple-minded fellow named Jamel (Zinedine Soualem), who helpfully risks his life on rooftops, usually in search of the wrong cat. The disappearance of Gris-Gris compounds Chloe’s isolation. “Why am I all alone?” she asks her gay roommate, who is lonely himself. “Guys scare you,” he says. “That’s why you have a roommate who’s gay.” She goes awkwardly into a bar, but doesn’t know any of the right pickup behavior, and ends up being accused in the toilet of trying to steal another woman’s boyfriend. Not that Chloe’s love life is quite that adventuresome; in one scene, the guy seems to hurry through the mechanics of sex because he’s eager to make a phone call.

All of this takes place in a kind of casual, offhand way: Chloe exudes the sense of living in her city, of being rooted in the neighborhood, of being not a character in a movie but someone you might see or hear about. And many of the other characters really do live in the district, and are playing themselves–particularly Madame Renee, a short, frizzy-haired, strongly opinionated little woman who is so uninhibited and convincing, you’d never guess she’s a real cat lady, playing herself.

The movie reminds us of what it must have been like to live in cities before air conditioning sealed the windows and television ended leisurely conversations on the front steps. Now we live in containers, like cargo on a ship. In Chloe’s Paris, people have a good sense of who lives next door and upstairs, and when she finally meets the neighborhood rock ‘n’ roll musician, she and everyone else have been listening to his drums for weeks. Of course this is changing; the district is being gentrified, and familiar old merchants are being replaced by high-priced shops.

The movie is made in the tradition of Eric Rohmer, who is the master of this sort of film. In his many movies, most recently “Rendezvous in Paris,” he follows people into the casual moments of their lives, and allows them coincidences and mistakes. Klapisch does the same thing. “When the Cat’s Away” is like a very subtle, curious, edgy documentary, in which we get interested in Chloe because she has lost her cat, and by the end we almost have to be reminded that the cat is missing.