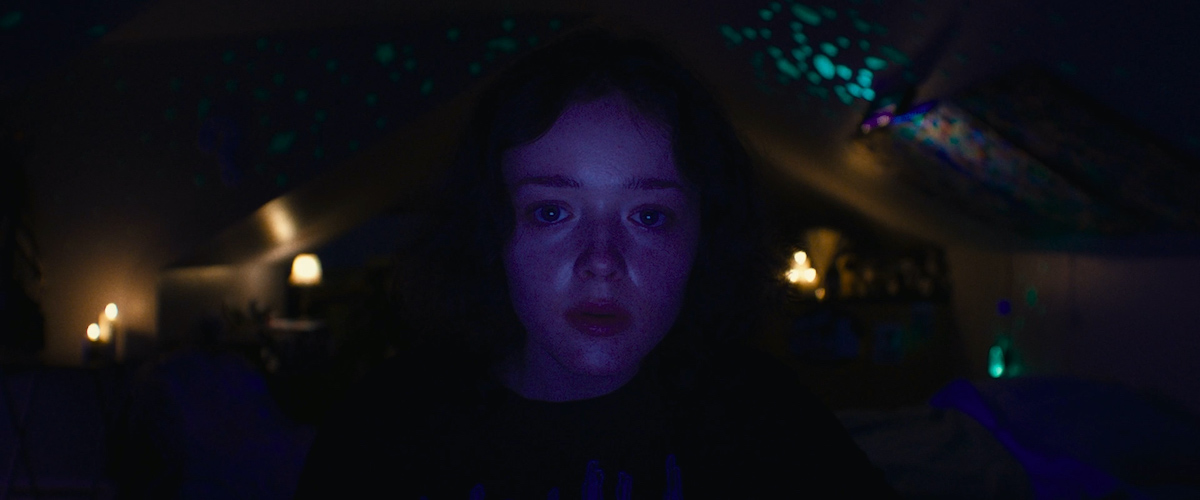

With her eyes of wide-set innocence, young Casey (debuting actor Anna Cobb) stares at her webcam late one night and repeats to herself, “I want to go to the world’s fair,” while gently slicing her thumb and smearing blood onto the screen. Focused and dedicated, she doesn’t as much as blink. Neither does the camera as it stays fixated on Casey’s porcelain face in one long take, captured from the POV of her monitor.

This “Candyman”-like ritual we witness in the opening moments of Jane Schoenbrun’s (“A Self-Induced Hallucination”) elusive, unnerving “We’re All Going to the World’s Fair,” a low-key psychodrama about the uncanniness of the virtual world entangled with an unusual coming-of-age tale, is in fact an initiation ceremony that is supposed to plug Casey into an online role-playing game called World’s Fair—apparently, the scariest of its kind. A lover of horror, Casey dreams of living inside one (“because it would be fun”) and welcomes whatever cryptic changes might enter her life from this point on; transformations that many who took the same challenge claim to have gone through via various online videos they contribute to the game’s creepypasta community portal. Some feel possessed, some feel a sensation as if a game of Tetris is being played inside their body (possibly the weirdest one), and some get swallowed up whole by their computers. It’s anyone’s guess what would be in store for Casey.

Slowly though, Schoenbrun’s slick and visceral (but sometimes, gruelingly monotonous) experimental outing introduces frights in the young girl’s existence that are several shades darker than whatever World’s Fair promises. Casey is lonely—so lonely in fact that we don’t ever get to meet her friends or parents, though one of them makes an aural-only appearance and yells at the kid to keep it quiet after hours. They are just inconsequential presences in her budding adolescence, one she prefers to navigate alone, amid the dark waters of the internet. If her surroundings are any indication—a non-descript, sparsely populated frosty town of empty roads and soulless strip malls—you can hardly blame her to look for excitement and a sense of belonging elsewhere. In that regard, Casey spends most of her time in her attic-level room, decorated with cozy glow-in-the-dark stars. When she can’t sleep, the flashing lights and soothing voices of ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) videos keep her company. In a quietly heartbreaking sequence, one such video even helps put her to sleep, filling in for the comforting bedtime stories of a gentle parental figure.

Amid blinking lights, fluorescent colors, and Daniel Patrick Carbone’s unsettlingly stalker-y camera angles (whenever Casey is captured from a POV other than her monitor’s), Schoenbrun slowly reveals their unique coming-of-age story with “World’s Fair,” one that doesn’t take place out in the real world, but in the bottomless online universe that frames Casey’s ever-shifting identity. Skeptically, we get to observe those increasingly menacing shifts in small doses, through the creative homemade videos she supplies to the World’s Fair site. An account called JLB that belongs to a much older man (Michael J. Rogers) quickly notices them and befriends Casey. What follows awfully looks like a spine-tingling account of grooming—“I’m worried about you,” claims JLB, insisting that he wants to protect Casey. But who exactly is this man behind his alarming black-and-white avatar that looks like a hand-drawn death-metal album cover? Is he a threatening presence with an abusive agenda?

In an unexpected and rather clever move, Schoenbrun decides to lift the curtain on him to show us a lonely man residing at a generic house of white moldings and marble bathrooms that couldn’t possibly be more ordinary or suburban. A similar emptiness visibly permeates his life. Maybe he is that groomer we feared him to be; but Schoenbrun gives us enough reasons to also think, maybe not.

It’s frustrating that “World’s Fair” doesn’t close the loop there and deviates from Casey at times for unwelcome periods—either to show us others’ nonsensical World’s Fair videos or to spend more time with JLB. But while their film manages to generate only a vague sense of disquiet on the whole, Cobb’s arresting performance holds our gaze and attention. She isn’t quite the ultimate awkward teen of cinema like Kayla of “Eight Grade”; but rather, an enigmatic chameleon with her dollish expression, pensive gaze, and internal screams we perceive more than we hear. Through Cobb, we take an alarming and up-to-date look into the life of any average contemporary teenager that grows up and establishes a voice mostly online, struggling to close the gap between the real and virtual. It’s that performance that elevates a film that often rings to be less than the sum of its parts.

Now playing in theaters and available on digital platforms on April 22nd.