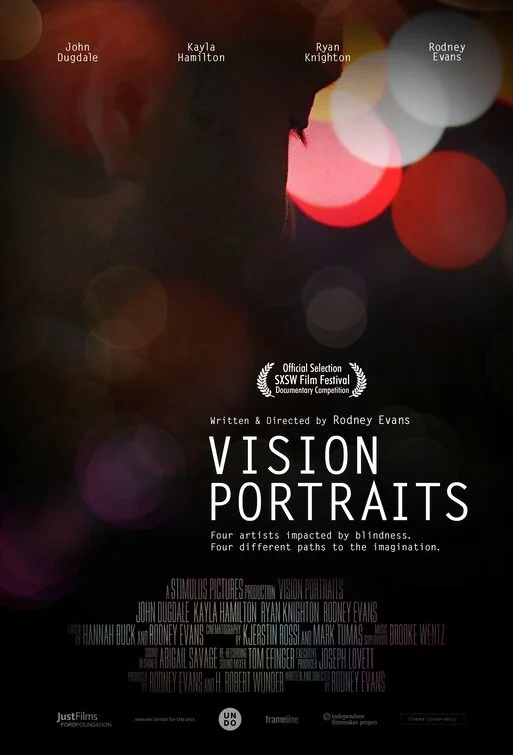

During “Vision Portraits,” the new documentary by writer/director Rodney Evans, I unexpectedly had what can best be described as a “come to Jesus meeting” with myself. This was surprising because I thought I had long since reconciled my own issues with my vision; I was wrong. This is a film about four blind and visually impaired artists who provide insight into their creative process while being brutally honest about how their various levels of blindness affect them. We hear Evans’ subjects describe the fear of waking up to discover their sight had deteriorated past the point of no return; some describe the moment when it eventually happened. There’s talk of signifiers of blindness—canes and eye patches and so on—and how the world interprets them. The director himself is one of the people profiled, offering up a self-inspection that triggered my own bit of reckoning.

Like the four artists who star in “Vision Portraits,” Evans, photographer John Dugdale, dancer Kayla Hamilton and writer Ryan Knighton, I am also someone who navigates an art form while dealing with blindness. Specifically, I am a half-blind film critic who lost sight in his left eye at 14 years of age. A retinal detachment and a botched surgery left me with a bad eye that, for a time, I covered with a prosthetic. This proved so painful that I had to give it up, leaving my rather gory left eye for the world to see now and forever. It bothers people. Sometimes it bothers me. But trust me, being scary-looking to some is far less painful than wearing that glass eye.

I had to get used to being half-blind, and all the stigma that entailed. But truth be told, my left eye wasn’t very good in the first place. It was lazy and I fought all childhood attempts to try and fix it. When Hamilton spoke of having her right eye covered so that her weaker left eye could be strengthened, I had an immediate sense memory response. I remembered my mother holding up flashcards with large letters of the alphabet rendered garishly in ’70s-era gold glitter, and I felt in real time how much it hurt to try and make those letters out. A blurry, lower case letter “g” invaded my mind’s eye, and the memory stung.

Evans and his co-stars each describe what they can still see, or how blindness is interpreted by their brains. Occasionally, editor Hannah Buck and cinematographers Mark Tumas and Kierstin Rossi supplement the words with visual approximations. For example, Evans tells us the extent of his vision and the screen blocks the territory around his image to establish his viewpoint. When Dugdale defines his blindness as seeing crescent moons and the aurora borealis, we’re given an idea of what that might look like. Dugdale describes the moment he went blind, and the screen jarringly cuts to black. “People think of blindness as darkness,” someone says, “but that’s not always true.” When I close my right eye, my left eye still occasionally blazes with rich, violent blues and reds, remnants of images projected on my shredded retina. That is, when my brain chooses to take a call from my optic nerve. Which isn’t often. Usually, it’s just all black now that my eye’s gone fully opaque.

“Vision Portraits” briefly gets into the medical afflictions that befell each artist. Evans and Knighton have retinitis pigmentosis, Dugdale had blindness brought on by HIV and Hamilton had arthritis of the eye and glaucoma. Detailed explanations of these ailments are not provided because the film isn’t about how each person arrived at their blindness so much as it’s about how their creativity didn’t stop once they reached that destination. Since filmmaking and photography are so reliant on images, it’s most interesting to observe and listen in on how Dugdale and Evans work. Dugdale’s old pictures are often as autobiographical as this film is to Evans, and there’s a scene where he says that while someone else does his bidding in terms of framing and composition, it’s still his bidding and authorship. Of course, Evans’ example of his work is rather meta—it’s the film itself.

As the interviewee with the most physical process, dancer Hamilton talks about the pitfalls of being blind in one eye. “If a dancer’s on the left, we’re probably not going to be together on the count,” she tells us. Excerpts from her one-woman dance show “Nearly Sighted” are shown, where Hamilton’s broad gestures and majestic movements are observed by an audience wearing eye-patches or glasses to put them in Hamilton’s perspective. “I feel most free when I just close my eyes and dance,” she says. I found her fearlessness of movement and her graceful navigation of space inspiring; watching her I kept thinking of how overly conscious I am about accidentally bumping into people or things on my left side. To torment me, my brain replayed some of the more embarrassing times that happened.

Like Evans, writer Knighton also teaches at a university. He’s also the most philosophical about his condition. “Blindness is a point of view,” he says, which in a way is the theme of “Vision Portraits.” He also tells a harrowing story about his eyes suddenly failing him one night, leading him into an involuntary game of chicken while driving. Knighton is also the source of much of the film’s humor, having written a memoir called Cockeyed that’s far from a miserable tale about going blind. “The world couldn’t hurt me if I were narrating it,” Knighton said, something I also quickly learned not too long after going half-blind. Instead of burrowing further into my own introverted nature, I became a social creature as a defense mechanism.

By the time we get to Evans’ story, we realize that he’s the connecting thread running through “Vision Portraits.” An award-winning filmmaker (he received the 2004 Special Jury Prize at Sundance), Evans ties all the elements together in his own section. He speaks about the fear of one day waking up completely sightless, about his original unwillingness to use a cane and about how important it was for him to showcase LGBT artists and artists of color in this film. He also explains how boring the descriptive service for visually impaired people can be, and how “Vision Portraits” has an audio track that’s as passionate and entertaining as the film is for sighted audiences. Evans is at first a reluctant subject, but as he opens up, and as his interviewees open up, the film achieves a quiet grace that’s quite affecting.

As entertaining as this movie is, it still managed to rattle me. I’ve been around blindness my entire life. No one in my family was spared some form of visual issue, and many of my relatives are blind or close to it. Some have canes, and it’s very likely that at some point, so will I. But watching Evans, Knighton, Hamilton and Dugdale interact with their art forms through talent and compensation made me think about the steps I take when seeing a movie I need to review—where I need to sit in the theater, how I have to move my head to make sure I absorb the entire image, how pissed off I get when the critics’ screening is in 3-D (since I’ve experienced 3-D with both eyes present, I know with one eye that it comes off as 2.25-D). How close I am to the computer screen right now because I’m too damn stubborn to make the print bigger and my life easier. I thought of all these things while watching “Vision Portraits” and for a little while, I felt shame. But this is an inspiring film, a funny and informative feature whose subjects were creative kindred spirits I’d never seen onscreen before. I realized that I was being represented here, and my unreconciled shame morphed into a sense of liberation.