The theory is that Brittany Murphy is trying to channel Marilyn Monroe, but as I watched “Uptown Girls,” another name came to mind: Lucille Ball. Murphy has a kind of divine ineptitude that moves beyond Marilyn’s helplessness into Lucy’s dizzy lovability. She is like a magnet for whoops! moments.

I remember her as a presenter at the 2003 Independent Spirit Awards, where her assignment was to read the names of five nominees, open an envelope and read the winner. This she was unable to do, despite two visits by a stage manager who whispered helpful suggestions into her ear. She kept trying to read every nominee as the winner, and when she finally arrived triumphantly at the real winner, she inspired no confidence that she had it right.

Some thought she was completely clueless, or worse. I studied her timing and speculated that she knew exactly what she was doing, and that while it took no skill at all to get it right, it took a certain genius to get it so perfectly wrong. She succeeded in capturing the attention of every person in that distracted and chattering crowd, and I recalled “Lucy” shows where everyone in a restaurant would suddenly be looking at her.

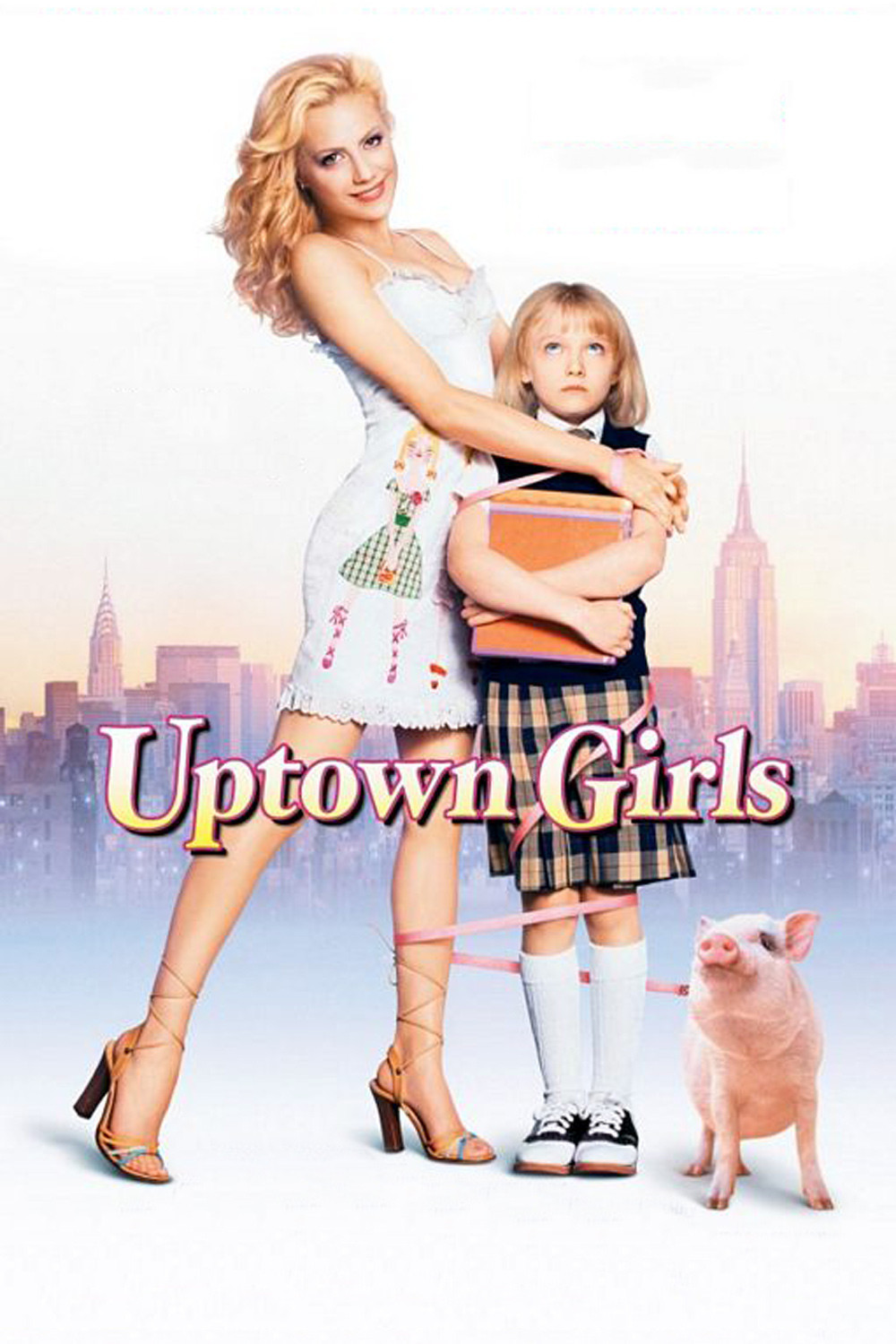

“Uptown Girls” gives Murphy an opportunity to channel Lucy at feature length. She plays an improbable character in an impossible story, but of course she does. She is Molly Gunn, whose father was a rock star until both parents were killed in a plane crash, leaving her with a collection of guitars and a trust fund administered by someone named Bob. As the story opens, Bob has disappeared with all of her money and she is forced to work for the first time in her life. This does not come easy to a girl whose only skills are as a consumer.

She gets a job as the nanny of an 8-year-old girl named Ray (Dakota Fanning), who seems so old and wise that when she tells Molly, “Act your age,” we see what she means. Ray is a dubious little adult in a child’s body, and although her family is rich, she has never enjoyed any of the usual rich-kid pleasures.

“You’ve never been to Disneyland?” asks Molly.

“Alert the media,” says Ray.

Molly still makes some effort to preserve her pre-Ray, pre-poverty lifestyle, and this includes an infatuation with a young singer named Neal (Jesse Spencer), who keeps his distance. He is only 274 days sober, he tells her, and has been advised to stay celibate for his first year. This turns out to be less than the truth, in a plot twist involving Ray’s worldly mother Roma (Heather Locklear; yes, Heather Locklear as the mother, and how time flies).

Ray is a hypochondriac who travels with her own soap and monitors her medications, and whose basic inability is to act like a kid. Molly has never grown up. Although this scenario is as contrived as most such movie plots, there is a way in which it works because Ray does seem prematurely old and Molly does seem eternally childlike; in the case of Dakota Fanning, I think we are looking at good acting, and in Brittany Murphy’s case, I think we are seeing something essential in her nature. Even in “8 Mile,” where she played Eminem’s girlfriend in a landscape of urban grunge, there was a part of her that was identical with Molly’s crush on the singer Neal.

I dismiss all cavils about the movie’s logic and plausibility as beside the point. This is not a move about plot but about personalities. Molly Gunn is a comic original, vulnerable and helpless, well-meaning and inept, innocent and guileless–or, more accurately, a person of touchingly naive guile. Murphy’s performance has a kind of ineffable mischievous innocence about it.

I also enjoyed the movie’s emotional complexity. “Uptown Girls” could have been a simple-minded, relentlessly cheerful formula picture. There is an underlying formula there, of course, with all problems resolved at the end, but Ray is anything but another cookie-cutter little movie girl, and Molly’s problems at times are really daunting. The surprise she gets about Neal’s behavior is not the sort of thing that usually happens in this genre. The director is Boaz Yakin, who made the searing movie “Fresh” in 1994. That one, too, was about a young kid with a lot of adult wisdom and an underlying sadness. “Uptown Girls,” on a completely different wavelength, suggests some of the same undertones. The screenplay, by Julia Dahl, Mo Ogrodnik and Lisa Davidowitz, based on a story by co-producer Allison Jacobs, takes what we might expect from this material and rotates it into a slightly darker dimension, where Brittany Murphy’s Lucy act is not merely ditzy, but even a little brave.