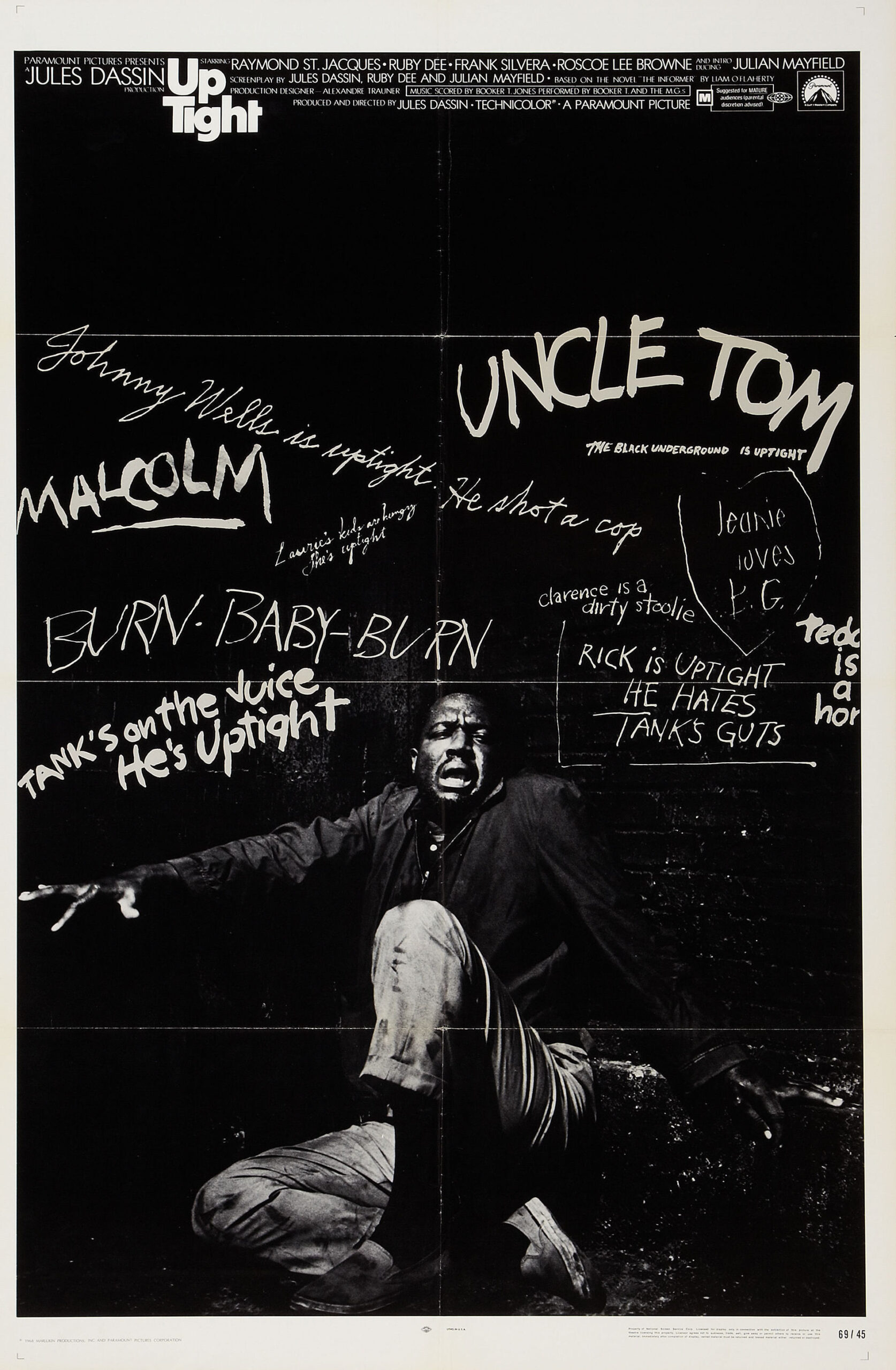

Jules Dassin’s “Up Tight” is a forthright treatment of black militancy. Somewhat to my surprise, it doesn’t chicken out. There’s no backsliding, toward a conciliatory moderate conclusion. The passions and beliefs of black militants are presented head-on, with little in the way of comfort for white liberals. White racists, I guess, will be horrified beyond measure. Good for them.

The blacks in the audience at the Roosevelt applauded “Up Tight” as a film that said something for them. It had nerve enough to portray the anger of the ghetto. Here was a movie in which the blacks are really black, and act and think like it, instead of masquerading as special cases like Sidney Poitier, the Nobel Prize winner. It’s remarkable that a major studio (Paramount) financed and released this film. Perhaps its success will make it possible for other movies to consider the American reality.

“Up Tight” is a good and interesting film, however, because of isolated elements. It has blunt and direct dialog; it has several powerful performances; It has moments of truth (as when the cops gun down a militant leader, while residents of a project rain down tin cans and invective). These moments, like several scenes between Poitier and Rod Steiger in “In the Heat of the Night,” have their own existence. To see them on the screen is enough; the movie as a whole doesn’t have to be perfect.

And it is not. Dassin made a strategic error at the very beginning, when he chose “Up Tight” as a remake of “The Informer,” Liam O’Flaherty’s novel (and John Ford’s film) about the Irish revolution. The transplant doesn’t work. The Irish and black revolutions have little in common, either in methods or in style.

What’s worse, O’Flaherty’s novel was about the downfall of an informer whose Irish conscience haunted him. Dassin tries to tell the same story, but he also tries to open it up and include the black revolution as a main plot element. In the O’Flaherty-Ford version, the revolution was kept in the background. The story was about the informer; the revolution could have been any revolution, any time.

Dassin is working with a specific time and place, and he has a lot he wants to tell us about it. This causes cumbersome shifts of tone as he moves between his informer (an earnest, not very bright alcoholic) and the militant leaders (direct, brilliant, zealous, brutal). The movie does not quite stretch enough to hold both halves of the plot. Our emotions become mixed, the story line wanders, and the conclusion lacks the impact it needs.

There is another problem. Dassin’s directing style is too impressionistic and arty for his subject matter. “Up Tight” should have been filmed in the greater reality of black and white, of course; but if it had to be in color it should have been in realistic color. Boris Kaufman’s camera cannot quite resist making the ghetto look like a set from “Porgy and Bess.”

Even though Dassin filmed on location in Cleveland, his backgrounds seem stylized. His decision to film mostly at night was a miscalculation; when his actors get outdoors in daytime, in a chase across a bridge and through a construction site, things look real. At night, even in the shoot-out scene, the backgrounds take on a dreamlike quality.

Dassin has been moving in this direction, unfortunately, in several recent films. After the breezy reality of “Rififi” (1954) and “Never on Sunday” (1960), it is disturbing to see him indulging in the most extreme arty stylishness in “10:30 p.m. Summer” (1966) and to a lesser degree in this film.

To be sure, a great deal is redeemed by the performances. Julian Mayfield is steady as a rock in his portrayal of Tank, the informer. It is a difficult role because Tank is largely inarticulate and unaware of his own motives. But Mayfield moves with confidence. When Tank visits the funeral wake of the revolutionary he betrayed, his confusion and grief are more moving than in Victor McLaglen’s similar scene in the Ford version.

Raymond St. Jacques, as a moderate turned militant, is authoritative and a little frightening. He has tremendous screen presence. Ruby Dee is tender and moving as Laurie, Tank’s girlfriend.

A final note. A white friend tells me he saw “Up Tight” the other day and was disturbed by the audience reaction: “There was a cheer every time a white guy got hit.” This should have been an educational experience, providing our side with the same sort of feeling that blacks have had for years when a black guy got hit. Or had to shuffle. Or had to squeeze inside the Stephin Fetchit stereotype. “Up Tight” finishes those days forever.