When Bill Clinton warned the fashion industry about heroin chic, perhaps he could have steered it toward films like “Twin Town” from Wales or “Trainspotting” from Scotland–two films in which drugs play a role and chic definitely does not.

“Twin Town” is a grotty examination of sordid lives, a reminder that many colorful characters are colorful only from a distance. The movie takes place in Swansea, Wales, a town that the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas once referred to as “the graveyard of ambition”–and he was a local boy, mind you. I have friends who live there, and who assure me that most of the events in the film take place on the other side of town. I hope for their sake they are right.

The story involves two families who work up an extremely unpleasant disagreement after the father of one clan falls off a ladder while working on a roof. Fatty (Huw Ceredig) is injured, and his twin grandsons see that as a golden opportunity for an out-of-court settlement. The roof belongs to Bryn Cartwright (William Thomas), a contractor, property developer and occasional cocaine dealer, who takes great pride in the greens of the local soccer club, which he controls along with most of the rest of the town. Cartwright won’t pay, and that leads to an undeclared war in which pet dogs are beheaded and house trailers are set on fire.

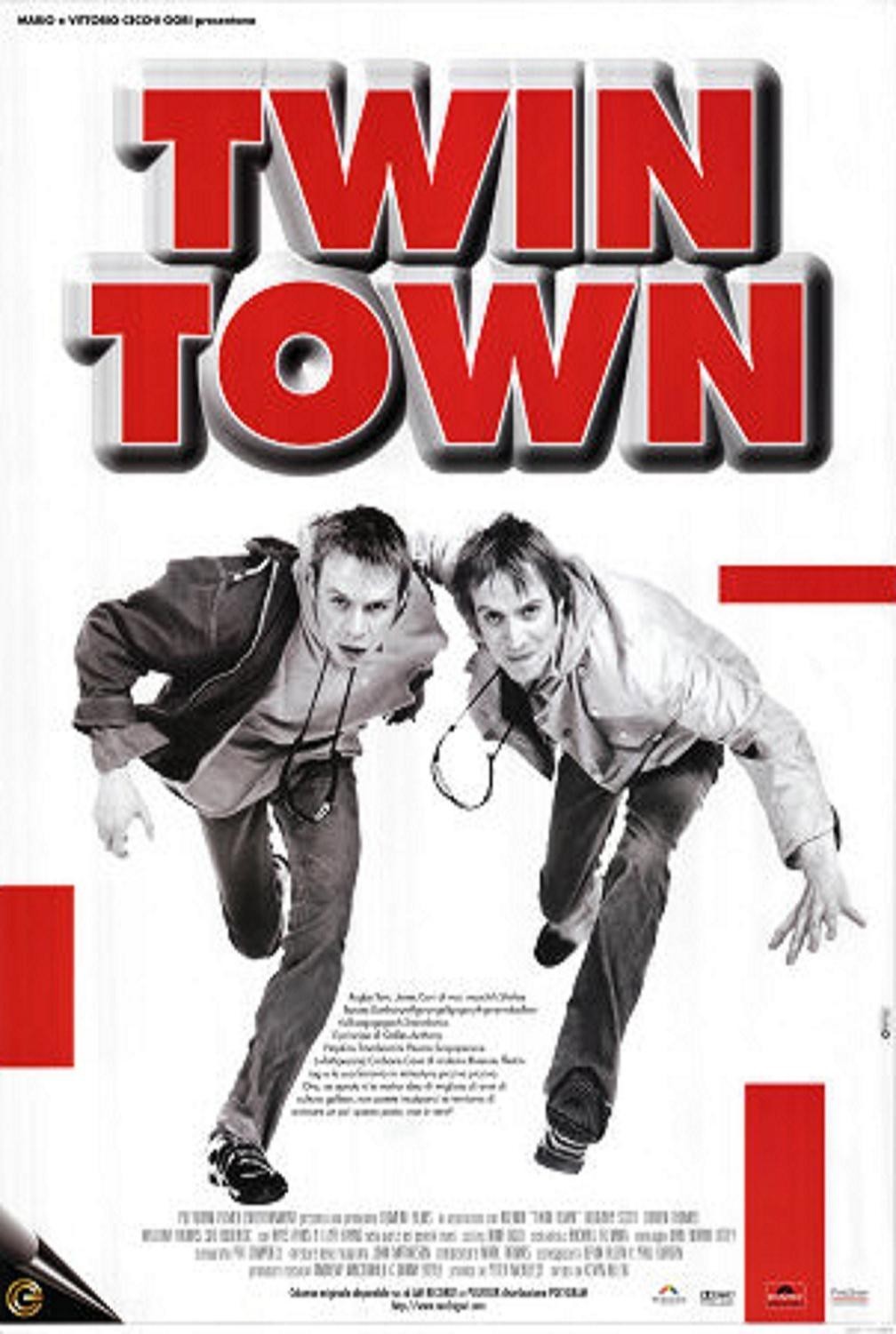

The twins are Julian (Llyr Evans) and Jeremy (Rhys Ifans). They’re actually not twins, only brothers, but everyone calls them twins (and they are played by brothers, despite the difference in the spellings of their last names). How to describe them? If you saw them coming, you’d lock up your daughters, your sheep and perhaps even your turtles. Swansea is not the graveyard of their ambition only because they never had any.

They live in a trailer on the outskirts of town, where the arts are manifested only in nail-painting. The Cartwrights live in a nicer house, where Bryn plays with model trains. The mothers in both families are dimwitted, and the children have not turned out well.

The plot veers uneasily between comedy and pathos, with episodes of gore. There are beatings, a murder, lots of drugs, two crooked and dense cops, the savage destruction of a soccer field, a particularly unpleasant hanging method, and also, lest we forget, karaoke sessions, a massage parlor, and a peculiarly poetic ending involving a local choir (one can just glimpse, at times, what must be the very pleasant other side of town).

I was not sure where the movie wanted to go and what it wanted to do–this despite the fact that it goes many places and does too much. Somewhere buried within it is a sweeter, more light-hearted story about its feckless lads, and then the hard-edged “Trainspotting” angle seems to have been added. But while “Trainspotting” had a clear vision and found a way to more confidently distinguish between comedy and the appalling, “Twin Town” is less sure-footed.

The movie’s executive producers are Danny Boyle and Andrew MacDonald, who were the director and producer of “Trainspotting.” Its director, Kevin Allen, is the brother of Keith Allen, an actor in “Trainspotting.” The connection is obvious: This film wants to do for (or to) Wales what the other did for Scotland. Some audiences will have trouble with the accents, but I find that in films like this (and Gary Oldman’s much superior new “Nil by Mouth“), it isn’t the words but the music, and you can nearly always sense pretty easily what is being said. “Twin Town” makes things easier by using variations of the same four-letter word as roughly a sixth of its dialogue.