With the recent announcement by its exiled founder that the Body Shop is an empty shell of commercialism, the 1970s, I suppose, are now officially over. “Together,” a sly, satirical Swedish film, shows the decade coming apart as early as 1975. In a commune in Stockholm, a mixed bag of adults, some with children, try to live according to their ideals, while human nature does its best to force them toward compromise, corruption, and–worst of all–realism.

Watching the film awakened memories of the time: a mother protesting against the gender-coding of pink and blue children’s blankets. Arguments about men doing the dishes. Denouncements of Pippi Longstocking as a materialist and capitalist. A child named Tet, after the North Vietnamese offensive. “Open relationships,” which have a way of ending in no relationships at all. By the time the kids start picketing for the right to eat meat, we see their point.

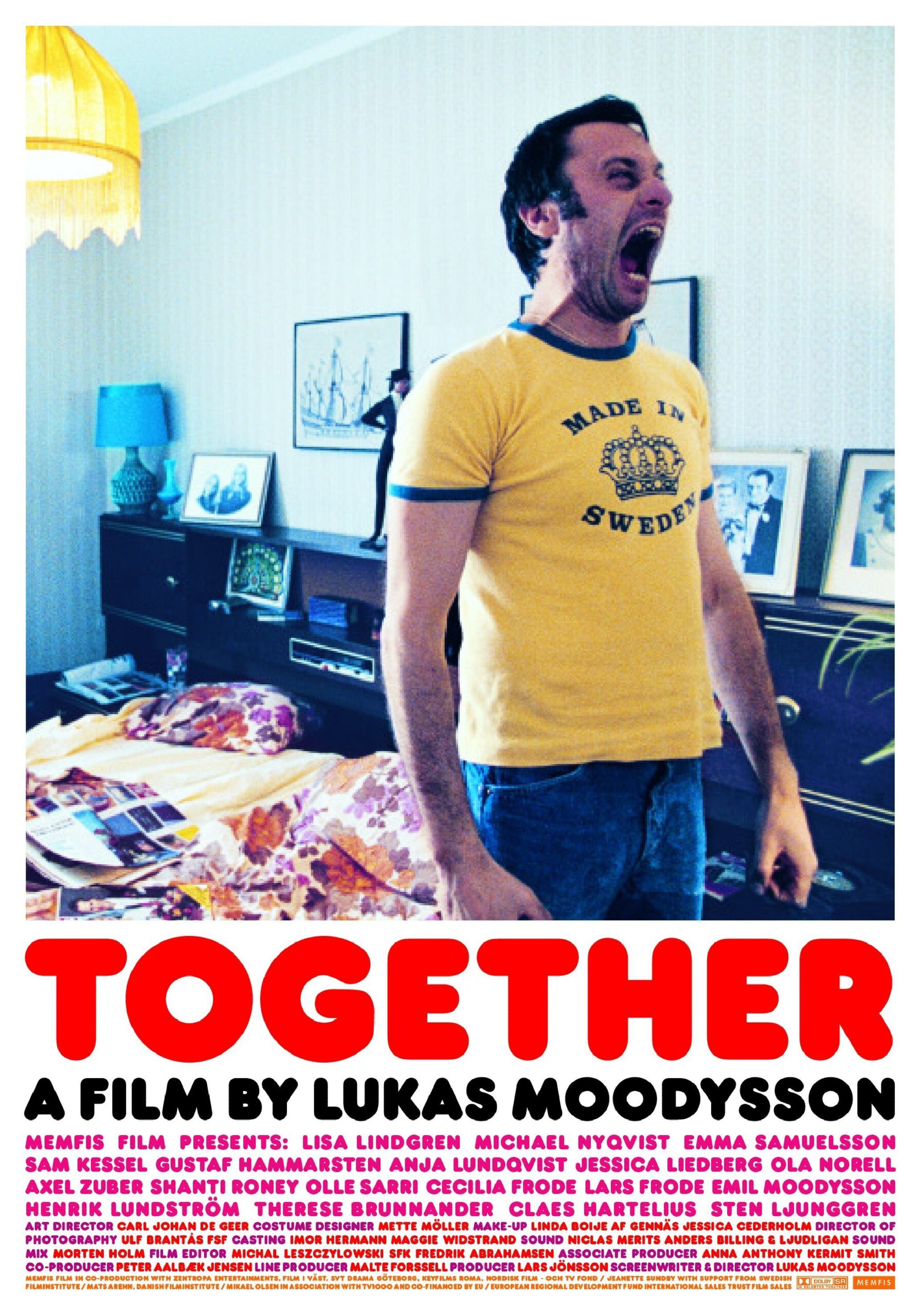

“Together” is the latest film by Lukas Moodysson, a distinctive new Swedish director, whose previous film, “Show Me Love” (1998), told the tender story of two misfit teenage girls who fall in love, even though one is probably straight. He has an ability to hold opposing ideas of the same character at the same time, which makes his people more intriguing and convincing than movie characters who are assigned rigid descriptions.

In “Together,” for example, an abused wife comes to the commune with her two children, fleeing her alcoholic husband. When we see the husband, he creates a drunken scene after taking his kids to a Chinese restaurant, and gets arrested. But Moodysson doesn’t leave it at that. He shows the husband at work as a plumber and introduces a minor character–an older man who calls the plumber just because he is lonely.

And eventually the plumber turns out to be more redeemable than some of the more righteous members of the commune.

That would include Lena (Anja Lundqvist), married to the commune’s leader Goran (Gustaf Hammarsten). They practice an open marriage, which means she makes love to the doctrinaire Marxist Erik (Olle Sarri), and Goran sits uneasily in the kitchen trying to pretend he doesn’t mind. One of the movie’s great moments comes when Goran finally, suddenly, unexpectedly, shows he does mind after all.

The movie’s best relationship is between two kids: Eva (Emma Samuelsson), the daughter of the alcoholic, and plump, 14-year-old Fredrik (Henrik Lundstrom), who lives across the street with up-tight parents who hate the commune. The two nearsighted kids discover they have exactly the same eyeglass prescription, and that is an omen, binding them together in an alliance that rejects both the crazy socialism at her house and the rigid conservatism at his. Meeting in the commune’s van or in each other’s rooms, they form an innocent friendship of mutual support that perhaps shows man’s natural state is in the middle, and not at the extremes. (There is also the ability of children to turn anything to their own ends. Eva’s brother Stephan and his playmate Tet have a game based on the Chilean dictator Pinochet, in which they pretend to torture each other with electrodes.) Sex causes more trouble than it is worth in the commune. One of the marriages has broken up because the wife has decided, for philosophical reasons, to become a lesbian. A gay man attempts unsuccessfully to use pure logic to persuade a straight man to sleep with him. (True, the genitals know no gender, but their owner-operators are rarely as open-minded.) There is a scene where a woman washes the dishes while naked from the waist down, justifying her decision with a medical complaint that might lead even the most open-minded commune member to prefer that she not wash the dishes at all. And all the time there seems to be a powerful subterranean force operating to sort these radical experimenters back into conventional, stable twosomes.

It may be that “Together” only wants to remember a time. That it does with gentle, observant humor. If it has a message, it is that ideas imposed on human nature may be able to shape lives for a while, but in the long run, we drift back toward more conventional choices. In the 1970s, hippies defiantly sprawled on the floor–in airports, movie theaters, classrooms, malls. Now they, and their children (and grandchildren), have gone back to chairs again, which were invented, as it turns out, for excellent reasons.