Some thoughts are nearly impossible to shake, especially for those of a certain mindset and/or under certain circumstances. For Shmuel (Géza Röhrig), it’s the thought of his recently deceased wife’s decomposing corpse.

She died of cancer, and now, the widower, a Hasidic Jew, has nightmares of her big toe, blackened and decaying, splitting at the tip and blooming like the petals of some ghastly flower. From his religious experience, Shmuel, a cantor at his local temple, knows that the Mishnah mentions 248 parts of the human body, so he is not exactly looking forward to 247 additional visions of similar horrors.

That’s where “To Dust,” the feature debut of co-writer/director Shawn Snyder, begins, as a devoutly religious man finds himself tormented by the specifics of his beliefs and the mystery that goes along with them. The particulars involve the idea that a piece of the soul remains in a human body after death, and that it only finds peace when the body returns to the dust of the earth. This is an especially terrifying thought for Shmuel, because he truly loved his wife and cannot bear the thought that some part of her would still be in pain—even after she endured the pain of death to cancer.

It doesn’t help that there is an aura of silence in the Hasidic community about the specifics of what happens to a body, plainly covered in cloth and buried in a pine coffin with three holes in the bottom, after death. If only Shmuel knew when his wife’s body would return to the earth, he might also know when he can stop thinking about a piece of her soul in agony, when every part of her deserves better.

If the setup to this film sounds morbid, it is. Snyder does not sugarcoat the realities of grief or biological inevitability, although he does, rather surprisingly, find humor in the protagonist’s unhealthy obsession. Despite the premise and the sometimes macabre turns of the plot, this film is a comedy—a melancholically existential and uncomfortable one, to be sure, but a comedy, nonetheless. It’s a successful one because Snyder and co-screenwriter Jason Begue follow through on Shmuel’s obsession in ways that might seem absurd yet are perfectly logical in the context of a husband’s grief, a religious man’s uncertainty, and a human being’s need to understand the incomprehensible.

At first, Shmuel tries to find answers in his faith, but from his rabbi (played by Bern Cohen), he only receives generalities and the usual condolences. He could find answers in his family, but his mother (played by Janet Sarno) wants him to move on with his life as quickly as possible. After all, he still has two sons (played by Leo Heller and Sammy Voit) for whom to care. The sons care enough about their father to note his despair. They believe that their father has been possessed by a dybbuk—likely the spirit of their mother—and, in a subplot that offers some relatively innocent relief to Shmuel’s story, they try to discover a way to exorcise the spirit.

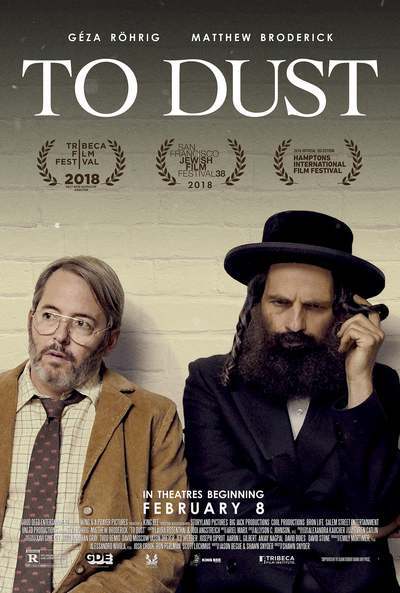

With the usual outlets for comfort proving unhelpful, Shmuel turns to science and specifically to Albert (Matthew Broderick), a sad-sack biology professor at a local community college. After some confusion and much convincing, Albert (who can’t be shaken of the belief that Shmuel is a rabbi and can’t get the man’s name right) talks Shmuel through the process of decomposition, using photos of a dead pig from a text book. We get actual, time-lapsed footage to go along with the graphic description, because, despite or on account of the film’s darkly comic tone, Snyder isn’t fooling around with the biological reality of death.

It’s not enough for Shmuel, who takes Albert’s hypothetical setup for a scientific experiment—to bury a recently deceased pig in the same way that Shmuel’s wife was buried—to heart. He buys a live pig from a local butcher and brings the animal to the professor’s apartment.

From there, it gets very strange, which is saying something for a story that already has so thoroughly embraced the ghoulishness of Shmuel’s fixation with death, decomposition, and partial, momentary damnation. The humor arrives with the introduction of Albert, who’s as hapless in his ways as Shmuel is severe in his attitude. Röhrig, brimming with grief and anger about the spiritual and physical mysteries of death, and Broderick, as a bumbling and dumbfounded man of reason, make for a fine pairing as a twisted variation on the rule of comedic opposites.

The rest of the story, which includes disposing of a murdered pig (for science, of course) and a cross-country trip from New York to a “body farm” in Tennessee, doesn’t relent from its morbid but thoughtful aims. The first part is obvious, but the thoughtfulness is in how Snyder uses this premise, these characters, the humor, and the specificity of Shmuel’s religious beliefs as a way to examine how we are all stumped by the nature of death.

Religion can provide some solace, but it can also complicate matters. Science can explain the natural processes, but even then, it cannot account for every detail in every situation. “To Dust” is about those contradictions and, in the end, about the ultimate one: that, to some questions, the only logical and spiritual answer is that there isn’t one—except whatever we make of it.