There are moments in “Time is Illmatic” where the camerawork flows like the smoothest MC navigating a difficult verse; one marvels at the technique yet is never distracted from the story being told. Director One9 and his co-editors David Zieff and John Kane opt for a style that is neither kinetic nor flashy. Instead, they establish a sense of presence, of being so in the moment that even the occasional visual effect feels natural and unaffected. The camera roams the way the human eye would, yet it knows the power of stillness, of letting the image linger and rest. These documentarians masterfully construct their vision to elevate and serve their subject. The result is more low-key than one might expect from a movie about rap. It is also more powerful, bypassing the expected artist braggadocio to stand on the rarely visited street corner of sociology and hip-hop music.

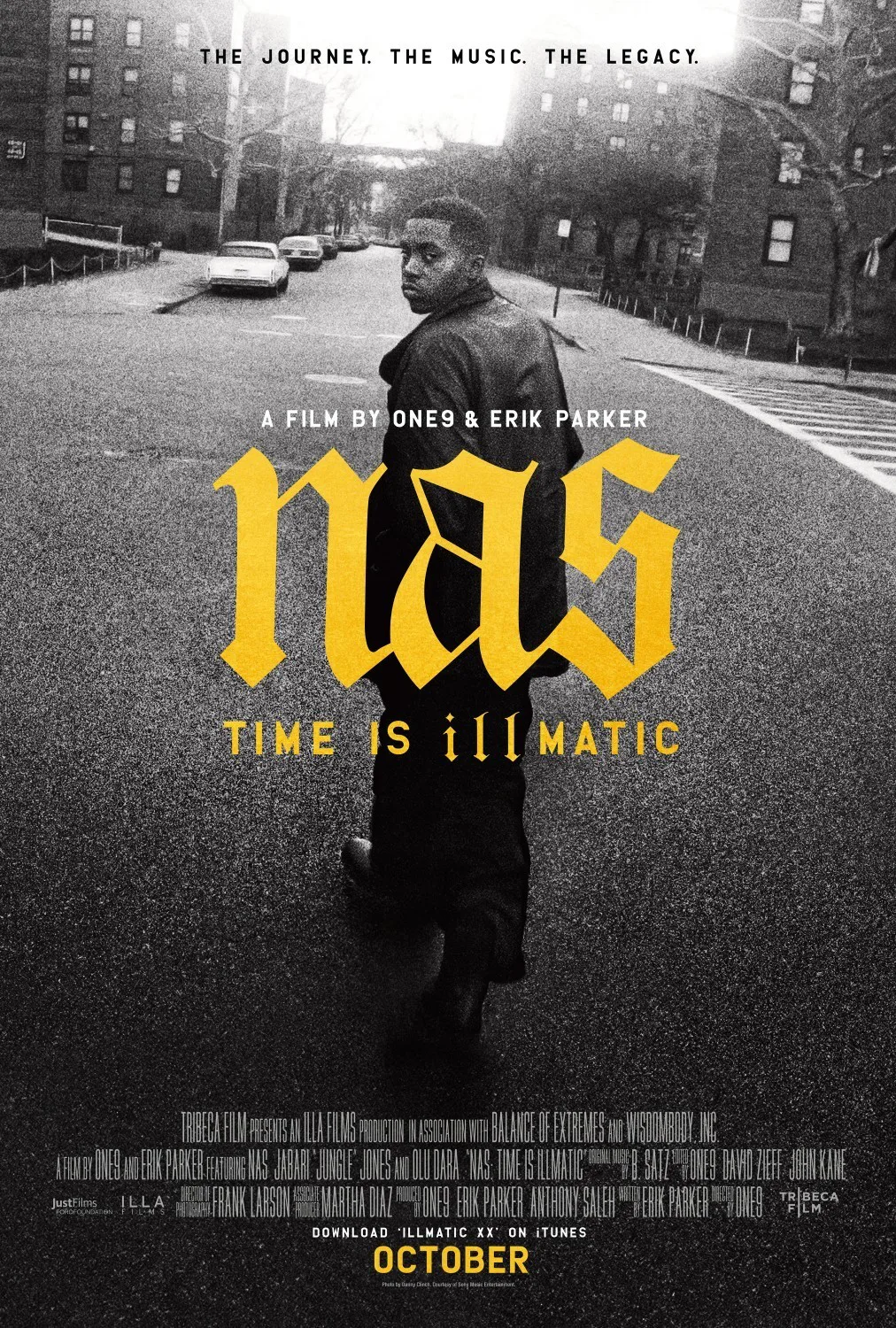

The subject of “Time is Illmatic” is the 1994 album, “Illmatic,” the debut work by the rapper whose government name is Nasir Jones. Nas, as he’s known in the musical universe, is the son of Olu Dara, a blues musician from Natchez, Mississippi and Ann Jones, a postal worker from North Carolina. His parents relocated him and his brother Jabari to the Queensbridge Housing Project in Long Island City, Queens, which is where much of “Time Is Illmatic” takes place.

“To survive here with a family was hell,” says Dara of Queensbridge. “Especially if you had no help. We had no help.”

Much of the film is people telling stories as they navigate the sidewalks and inhabitants of Queensbridge—this is more a walking documentary than a talking heads one—and One9’s camera is there with them, drifting around and settling like the proverbial fly on the wall. When the credits roll, viewers will realize that “Time is Illmatic” represents and explores not only the album but also the environment that fostered it.

Walking in, one might expect “Time is Illmatic” to ramble on about how successful “Illmatic” is. After 20 years, the album remains one of the most influential rap albums ever produced. We get the occasional artist like Alicia Keys or Erykah Badu speaking of how the work influenced them, as well as words from the producers of several tracks on “Illmatic.” But the film doesn’t dwell on sales, praise and studio time. The primary question “Time is Illmatic” wishes to focus on isn’t “how did Nas do it?” but “why did Nas do it?” Evidence that the film is part history lesson occurs early on: The first mention of Queensbridge Projects is accompanied by a picture of FDR signing a public housing bill and footage of NYC mayor Fiorello LaGuardia laying cement at the foundation of The Bridge’s first building in 1939.

Footage of Nas prowling the stage as he performs many of the tracks from “Illmatic” are contrasted with the soft-spoken, introspective man who serves as our main character. “Time is Illmatic” films him in several locations, from the couch in his house, to his car, to his old stomping grounds in the projects. As expected, he is a gifted storyteller, spinning yarns about hanging out with his best friend, Ill Will, and how excited they were when a song by MC Shan about their neighborhood dropped. He speaks highly of his late mother, whose presence and influence haunt “Time is Illmatic,” and is candid about the neighborhood that nurtured, inspired and threatened him.

The filmmakers interview Nas’s second grade teacher, Mrs. Braconi, which at first seems like a cutesy device to shed light on what young Nas was like. In actuality, it’s a jumping off point for commentary about the public school system in the 1980’s. Mrs. Braconi points out how enthusiastic and artistically expressive Nas was, then we learn that Nas left school in 9th grade. “When the schools have no money, you get a no money education,” Nas tells us, comparing his high school to an overcrowded prison where the students learned little. A no money education leads to no money post-education, which leads to some of the hard choices Nas discusses in his songs.

Regarding those songs, Nas and several of his producers speak of how their environment shaped what “Illlmatic” wants to say about the lives of the underprivileged and underrepresented. Lyrics and songs are studied with a level of introspection and detail rarely seen in any mainstream media discussion about rap. Nas explains the reason why “One Love” unfolds in epistolary form, and why Brian DePalma’s “Scarface” influenced “The World Is Yours.” People like Pete Rock and Q-Tip remind us that, long before rap concerned itself with being fancy, a famous rapper once noted that it was “CNN for brown people.” It’s easy to dismiss the violent, profane lyrics on “Illmatic” as mere thuggery only if the album is abstracted from the harsh realities Nas and other rappers experienced. Q-Tip wisely draws our attention to the slivers of hope that keep breaking through in the album’s most turbulent songs.

In addition to the celebrities and producers, we also meet Nas’s brother Jabari, who goes by the name Jungle. As any brother is wont to do, he provides color commentary and clarifying, objective detail about his famous sibling. One9 follows him through the neighborhood as he talks about some of the events and daily routines that ultimately populated many of the lyrics on “Illmatic.” It is Jungle who is tasked with some of the most effective moments in “Time is Illmatic,” from previewing us on the tragic fate of Ill Will to revealing what happened to many of the people who posed for a group picture during the photo shoot for “Illmatic.”

One9 also follows Nas in Queensbridge, where his comfort level has no hint of fakery. As I know firsthand, when you leave your ‘hood, you take it with you in your heart. When you return, you easily fall back into its cadences as if you’d never left. As you roam, memories of joy co-exist with more traumatic ones, and you reconnect with those you knew. Nas speaks with no hint of celebrity to folks, pausing to provide some inspiring words to a kid who shares his name. “All Nasirs are kings,” he tells the kid before stooping down to take a picture with him.

“Every hood is haunted by the brothers that walked through there,” Nas tells us. “The essence of them is still there.” He says he wrote “Illmatic” as “something that was proof that I was here.” Moments like this provide “Time is Illmatic” with a strong representation of how one’s world influences one’s art, and as someone who shared some of the same experiences “Illmatic” describes while growing up in my own ‘hood, I was extremely moved. Viewers and fans will surely get their share of sing-a-long moments in the concert footage, but they’ll leave more knowledgeable about, or reminded of, the culture from which those great songs evolved.