“Your work is novel, brilliant and dangerous,” his departmental superior says to Dr. Alan Stone (Richard Gere), a psychiatrist in the midst of conducting a series of revolutionary therapy sessions on three schizophrenic patients who all believed they were Jesus Christ. While Jon Avnet’s (“Fried Green Tomatoes”) drama is based on Polish-American social psychologist Milton Rokeach’s groundbreaking work between the years 1959-61 and his resulting case study book, “The Three Christs of Ypsilanti,” it sadly lacks the aforesaid freshness, smarts and risk Rokeach’s landmark group therapy experiment inherently possessed. In lieu of those qualities, “Three Christs” opts in for frustratingly broad characters that feel like half-considered caricatures, while Jeff Russo’s sentimental, strings-heavy score flattens whatever modest edge the movie might have had.

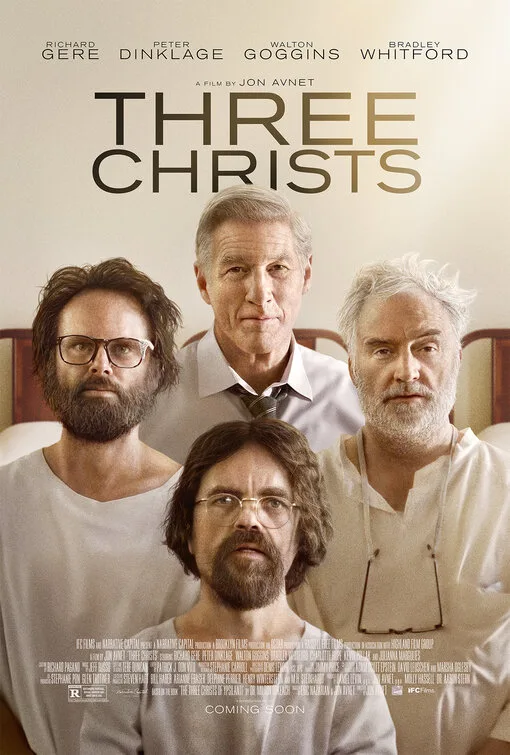

Finally getting in front of non-festival crowds after its 2017 Toronto International Film Festival premiere, “Three Christs” could have been a lot more than a shallow “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest”-lite, had the joint script by Avnet and Eric Nazarian bothered to define the three patients Dr. Stone observes in the same room together at a Michigan facility, beyond their basic oddities and delusions. The self-professed Christs are Clyde (Bradley Whitford), Joseph (Peter Dinklage) and Leon (Walton Goggins)—all dedicatedly portrayed by their respective actors despite the little depth they’ve been given on the page. Clyde insists he can smell an unpleasant odor no one else can and brands himself as Jesus, but not from Nazareth. Both Joseph and Leon demand to be called by their righteous names, while the former sports a posh British accent and the latter, a constant sexual drive as well as an obsession with Dr. Stone’s young research assistant Becky (Charlotte Hope). Another prominent figure in the proceedings is Dr. Stone’s brilliant wife Ruth (Julianna Margulies), an ex-assistant to her husband who once sat in the associate chair Becky now does.

While Avnet briefly engages with the female experience in the field, his inspections don’t dig a lot deeper than the casual sexism the two generations of women are exposed to in their respective roles in the company of a man with a God complex. (The film could also have been called “Four Christs,” but perhaps that would have been too on the nose.) Though the movie’s most significant deficiency is a lack of insight when it comes to the era’s cruel approach to psychotherapy—Dr. Stone empathetically launches his trials in direct opposition to malicious electroshocks and heavy drugs of the time, and yet the pioneering nature of his work never really registers when historical context around it is defined in basic good vs. evil terms. Negligent plot diversions that involve drugs and alcoholism, simplistic dialogue lines (“Freud said there were two basic instincts. What were they again?”), and an all too conventional framing device that signposts the tragedy to come also don’t help the matters.

Still, Gere’s charisma and Hope’s radiant presence keeps things somewhat watchable, with occasional flourishes of humor amongst the three patients giving the picture a jolt when they jointly engage in art and music. Also noteworthy is Tere Duncan’s cozy, ’50s-based costume design that has the wisdom to repeat garments to build a believable wardrobe for Becky. If only some of that plausibility had rubbed off on the story, dialing down its often ill-considered whimsy that doesn’t seem to know how to approach its original material with the seriousness it deserves.