When there is a global call to arms, the uplifting escape that movies can offer is a necessity and the unique insight that women provide is essential. Both are especially needed when, at any given moment, death lurks around the corner and chin-up optimism is in short supply. That is the rah-rah message behind “Their Finest,” which attempts to wed a ‘30s-style workplace screwball comedy with a misty-eyed World War II drama and, save for a few patchy spots, mostly succeeds.

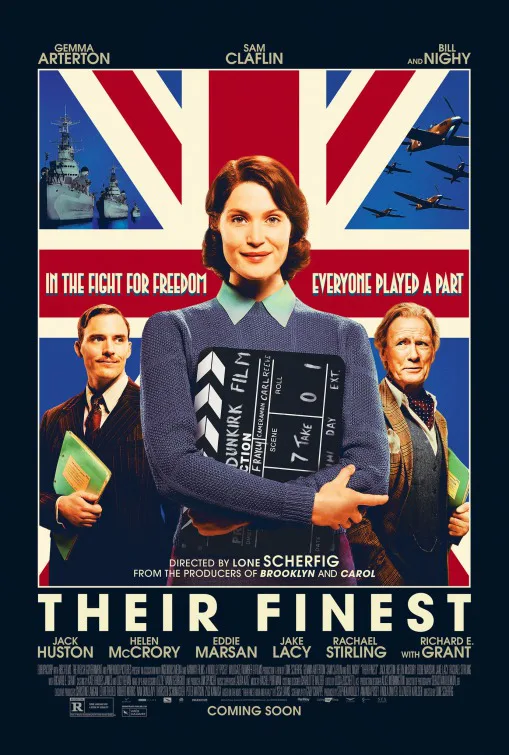

The big headline here is that Danish director Lone Scherfig has at last achieved a worthy femme-forward follow-up to her sly coming-of-age tale from 2009, the Oscar-nominated “An Education,” with another portrait of a London-based young woman adapting to a period of social upheaval. But instead of a British schoolgirl in the ‘60s, Catrin Cole (a glowingly rosy-cheeked Gemma Arterton) is a displaced Welsh lass in 1940 looking for a way to pay the rent during the Blitz, when many men were fighting overseas. Her lover-boy companion, Ellis (Jack Huston), hobbled in a past conflict, is a struggling-artist type without a steady income of his own.

Catrin’s wordsmith skills land her a job in the Ministry of Information’s film division, where she upgrades propaganda scripts that aim to lift morale and instill pride. Originally tasked with inventing women’s dialogue—dubbed “the slop”—in war-related shorts, she is soon recruited to help flesh out a full-length civilian rescue-mission adventure that unfolds during the Battle of Dunkirk, featuring comely patriotic twin sisters who become boat-commandeering heroes. Instead of toiling in a factory, Catrin is a Rosie the Riveter, wielding a typewriter instead of toting a power tool. She isn’t paid as much as “the chaps” at first, but is soon enough treated as an equal by male colleagues as she regularly saves the day with the perfect plot fix or line adjustment

As for the world outside their offices, it is one of increasing chaos and rubble-filled streets as shrill air-raid sirens, swooping German bombers and earth-shaking explosions are regular occurrences while neighbors, friends and family members can be killed without warning. Not that romance isn’t in the air. Competitive sparks fly between Catrin and cynical fellow scribe Tom (Sam Claflin, tribute Finnick in the “The Hunger Games” franchise, who is given a mature makeover with specs and a ‘stache) as they mutually peck away on their keyboards. The love triangle that “Their Finest” puts forth is definitely not the best part of the story since it is quite clear that Ellis neither supports nor is good enough for Catrin. More amusing is how she and Tom go from rivals to a well-tuned team, complementing one another at work and beyond.

The film crews, both Scherfig’s and her fictional one onscreen, deliver picturesque backdrops on a modest budget. The seaside locales that stand in for Dunkirk offer a scenic oasis from the horrors back home and the peeks into how primitive cinematic effects were achieved are fun to witness. Equally impressive are the outbreaks of violence, such as when a horrified Catrin stumbles upon a bloodied body amid scattered store mannequins as dust obscures the carnage.

The supporting cast is a special effect in and of itself, as various stellar British actors parade by, including Richard E. Grant, Eddie Marsan and Jeremy Irons. But no one fulfills his duty better than that lanky slice of wry known as Bill Nighy, who plays an aging matinee idol making hay as younger thespians are otherwise engaged. As Ambrose Hilliard, the star of a pre-war detective series, Nighy is never less than splendid, whether cozying up to Catrin so she plumps up his self-sacrificing role as drunken Uncle Frank, patiently coaching the real-life Audie Murphy-style American war hero in the cast (Jake Lacy, leadenness personified) used as bait for Yankee ticket buyers or conducting a sentimental group sing-a-long in a pub.

As for the feminine side of the equation, Rachael Stirling, as a Ministry wonk in charge of making sure the film does not go off the rails, gives off Eve Arden vibes in natty Marlene Dietrich-style menswear—and on several occasions gives nudge-nudge hints of being proudly lesbian. Meanwhile, Helen McCrory keeps up with Nighy as Sophie, his flinty yet flirty middle-age Polish agent, who steps in after her brother (Marsan) becomes a bomb victim. I wished that Arterton—who can pretty-cry as well as anyone and accepts proffered hankies with flair—would have instilled Catrin with a dose of Jean Arthur-ish snap and crackle, but her character’s calm confidence in herself somewhat makes up for the lack of more overt displays of spunk.

“Authenticity” is a byword among the filmmakers onscreen and for Scherfig, too, since she has stocked her behind-the-camera army with a raft of female talent in the roles of screenwriter (whose script is based on a book by a woman author), producer, composer, editor, production designer and more. Authenticity also shows up in two late-arriving sad outcomes—one surprising, one not. As well-earned emotional high-points, they deserve a salute.