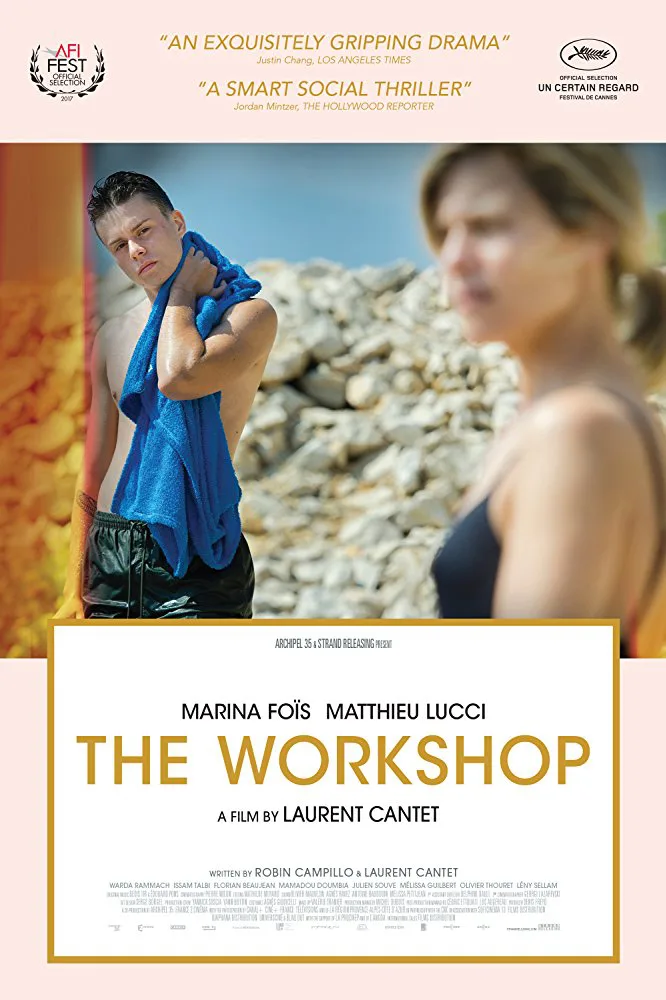

Talk about eerie parallels. Waking up in the morning before writing this review, I look at the news and see the smiling face of one Mark Anthony Conditt, the 23-year-old suspected in the recent Austin, TX, bombings who blew himself up in a van as police closed in. What strikes me is how much resemblance he bears to Antoine (Matthieu Lucci), another troubled young white guy who’s at the center of the film I watched the night before, Laurent Cantet’s “The Workshop.”

There are differences, of course. Where Conditt was an American in his early 20s, Antoine is French and in his late teens. Both were attracted to right-wing ideas and, it appears, drawn toward violence as a way of working out inchoate personal frustrations. Conditt, though, is smiling in the photo I saw in the news. Antoine never smiles.

It takes a while for “The Workshop” to establish Antoine’s centrality to its story. When the film begins, he’s just one of several teenagers taking part in a summer creative writing workshop in the French Riviera port of La Ciotat. The workshop’s genesis is never explained but it appears to be a city social program that includes at least some teens who, like Antione, are unemployed. An established author, Olivia Dejazet (Marina Fois), has been brought in to lead the class, and the students privately joke about her hoity-toity Parisian accent and “pretentious” manner—criticisms which are mostly typical teenage and provincial backbiting.

Olivia seems sincere and solicitous of her students, a multi-culti mix that’s very believable in this corner of France: there are a couple of Arabs, one black guy and whites who come from both working-class and middle-class backgrounds. The teacher’s aim is get the group to generate the material for a thriller, and initial scenes show them tentatively beginning to discuss the story’s parameters. Should it be set in the present or the past, or perhaps a combination of the two, connected by flashbacks? Using the past, when La Ciotat is supposed to be the setting, brings up the city’s history both as a successful commercial port that failed and as the setting for Communist-led labor strikes. The town now contains a posh marina housing the yachts of millionaires—another setting rife with dramatic potential.

Will the bad guys be terrorists or criminals or maybe even a vengeful labor organizer? Such questions prompt mentions of “Bataclan” (nightclub) and “Nice”—sites of recent terrorist attacks in France. It’s here that political divisions in the teens begin to surface, but the film doesn’t really begin to reveal Antoine’s place in this dialectic until it follows him home, where we see that he’s alienated from his working-class parents and occupies himself exercising and flexing his muscles in front of a mirror. He also watches Internet videos of right-wing underground leaders spouting nativist rhetoric and rallying their (mostly) young, white male supporters.

Interestingly, when the classroom political divisions escalate, Antoine doesn’t advance the idea of a violent fictional protagonist who’s motivated by political ideas. He says he’s interested in killers who are motivated only by a desire to kill. When Olivia finally gets some of the kids to put pen to paper, he brings in and reads a story that tells of just such a killer unleashing a bloodbath on the decks of a yacht. The teacher and the other students are equally stunned and offer only confused responses.

Understandably, Olivia develops a special interest in Antoine and begins to investigate him on social media, where she finds images and videos of him in camouflage face paint and brandishing pistols with young friends. But Antoine also investigates his teacher and one day brings to class and reads from one of her novels. He offers a derisive critique of the superficiality and literary frippery of a scene of violence the book describes, and the analysis both embarrasses and stings Olivia. She becomes increasingly convinced that the boy is not only deliberately provocative but potentially very dangerous.

Laurent Cantet is best known for “The Class” (2009), which used a documentary style and extensive improvisations by its teenage cast to trace a teacher’s interactions with his lower-class high school students over a school year. “The Workshop” obviously starts out looking similar but soon reveals its differences. When the workshop delves into discussing thrillers, the film signals that it might end up verging in that direction itself. So: will it be a typical French talkathon, with capable actors and a pleasingly naturalistic look, or become something more dangerous and pulse-pounding?

I liked the fact that Cantet effectively walks a knife’s edge in answering (or delaying an answer to) that question. The film keeps you guessing, not only as to where the story’s going but what kind of film it will turn out to be. And while that’s ingenious and intriguing, there are flaws that I found either unnecessary or puzzling. For one, the other kids in the class might have been more fully and interestingly drawn. As is, they fade into the background when the focus narrows in on Antoine. Secondly—and most oddly for a French film—there’s no mention of sex. When Olivia finally gets Antoine to sit for an interview (pretending it’s research for a book), she doesn’t ask, “Do you have a girlfriend?” or anything similar. Given how many of these young white killers seem motivated by sexual frustration or vengeance, that’s strange.

For much of its length, “The Workshop” effectively asks if its underlying situation is how conscienceless killers like Mark Anthony Conditt are generated, or if Antoine belongs to the huge number of boys worldwide who are similarly motivated but never pull the trigger. It will be up to viewers to say how satisfying the film’s answer is. For myself, I couldn’t avoid the irony that, in finding it ultimately rather superficial and self-satisfied in that particular Parisian way, I was echoing Antoine’s criticism of Olivia’s writing.

Side notes: Two omissions here are curious, unless French cultural memory is rapidly eroding. This film’s setting has a storied place in cinema history as the location of “Arrival of a Train in La Ciotat Station,” the short that legendarily sent patrons scurrying for the exits when the Lumiere brothers showed it publicly in Paris in 1895. Why no nod to this? Even odder, Antoine’s descriptions of his ideal killer inevitably recall the protagonist of Camus’ The Stranger, one of the most celebrated French novels of the last century. Was there no acknowledgement of this under the assumption that few filmgoers under 50 have ever heard of le existentialisme?