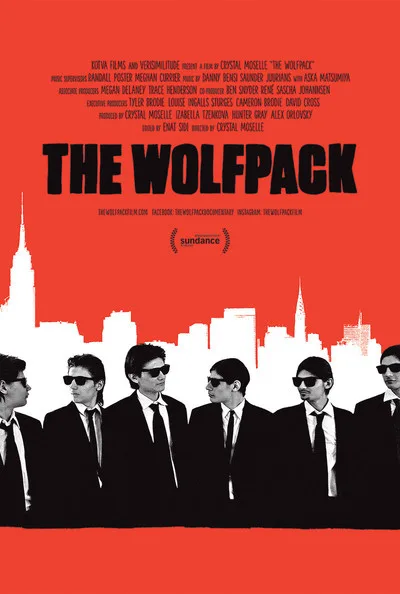

The story behind “The Wolfpack,” one of this year’s buzziest Sundance docs, is one of that blessed event in filmmaking—blind luck. Director Crystal Moselle was walking down an NYC street one day when she saw six young men in suits and sunglasses coming in the other direction. They passed by her and Moselle had the instinct to turn around and ask them their story. And what a story she heard. The Angulo brothers—six young men with similar features and long black hair—brought her up to their tiny apartment, shared with a shy mother and aggressive father. Moselle learned that the Angulos had barely been allowed to leave this apartment over the course of their entire existence, raised in a secluded, near-cult family, allegedly driven by father Oscar’s fear of the real world. With an abusive father and no contact with the outside world, the Angulos became obsessed with feature films, writing out scripts for flicks like “Reservoir Dogs” and “Pulp Fiction” by pausing the DVDs and then reenacting them in fine detail. Film became their only portal to the real world, their way to express their fears and desires. And Moselle caught these boys just as they were moving from a world lit by a television tube to one with sunlight.

Clearly, Moselle had instant affection for the Angulo boys. It’s hard not to. They are remarkably sweet and gentle, and the sadness in their eyes, especially the older ones, when they discuss their heartbreaking upbringing and fear of the real world is the kind that makes you want to give them a hug. Early in “The Wolfpack,” the older boys ask if she got up to their apartment OK, as if something bad would happen to her in the lobby, and are excited to cook dinner for their special guest. It’s clear from Moselle’s verité style, in which she doesn’t often seem to ask follow-up questions but let the boys come to their own emotional conclusions, that she was very concerned about these young men, as anybody would be. But the arms-length approach can be frustrating. There are times when the Angulos seem to be directing “The Wolfpack” more than Moselle, and it’s an incredible story that would have benefited from a surer hand.

Despite the sense sometimes that Moselle isn’t driving “Wolfpack” in the way needed to make it truly work, she undeniably finds some beautiful moments in the trajectory of the Angulos, although they are sometimes so fleeting as to frustrate when they aren’t further developed. The most striking moment comes when an Angulo says that “We were frightened kids…that’s one of the first memories I have,” when discussing the abusive Oscar, who one claims ended every fight with mom with a slap. Moselle then cuts to a figure of Mukunda, the most reflective of the boys, in a detailed Batman costume, before reenacting “The Dark Knight.” Do the boys relate to macho, male-driven films because they haven’t had a decent male role model in their lives? Are they drawn to the melancholy of Nolan’s take on the character because it reflects their own?

Much of “The Wolfpack” is undeniably moving, especially as the boys come out into the real world, frightened and unsure of themselves. They see “big f**king trees” and compare them “The Lord of the Rings.” They see “The Fighter” and are happy that their ticket money will go to Christian Bale. There’s a naïve, heartwarming approach to the power of cinema in “The Wolfpack” that clearly appealed to the cinephiles in Park City.

Could Moselle have found a way to make this incredible story into an incredible film? Part of the problem may be that she came upon the Angulos at the time they were emerging from their near imprisonment and that made her hesitant to pry into their pasts for fear of placing blocks in what seems like a road to recovery, as anybody would be. When mom says that she grew up in the Midwest and thinks public school “socialization” is not that good, anybody would almost feel impolite to pry further into her background or the falsity of that belief. And yet that’s what separates great documentaries from good ones.