It is clear fairly early in “The Thief” that the title character represents Stalin, and it’s one of the strengths of the film that the symbolism never gets in the way of a convincing, heartbreaking story. The movie, one of the 1998 Oscar nominees for best foreign film, never pushes too hard to make its point, but what’s clear in every frame is the sense of hopelessness and betrayal in the years after World War II.

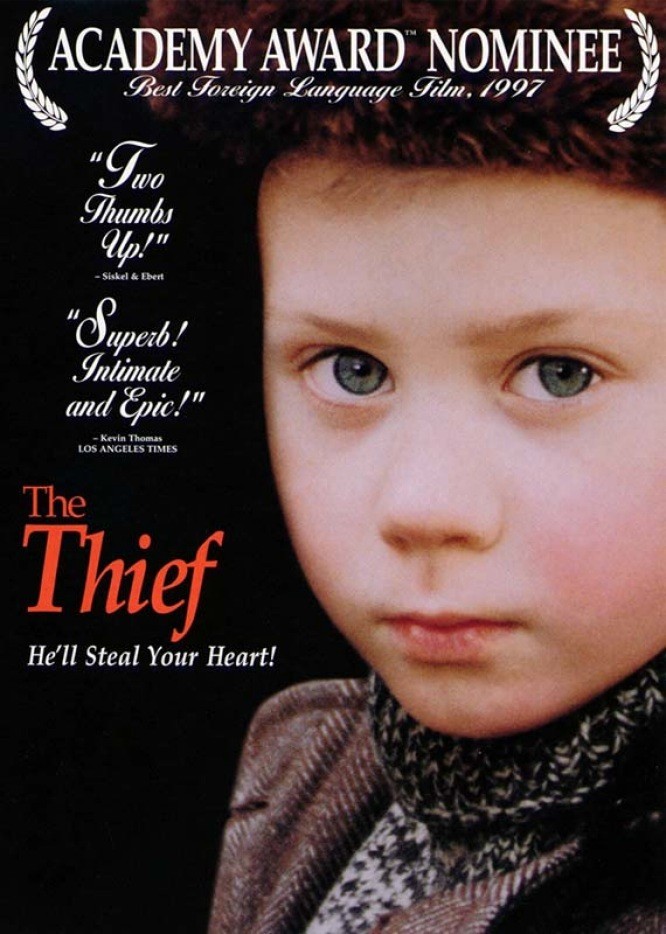

The movie is told through the eyes of Sanya, who is born on the roadside to a homeless mother in 1946, the first year of the Cold War. He is 6 when he and his mother are approached on a train by a man named Tolyan, who is dressed as an Army officer and may once have been one–or perhaps not. Nothing about him is trustworthy, which the mother and boy learn through many hard lessons.

“Uncle” Tolyan is a charming, mustachioed man, tall and robust in a land where many citizens seem weak, ill and hungry. It takes money to be healthy, and Tolyan is a thief–not only of money and possessions, but also of hearts. The mother, Katia (Ekaterina Rednikova), falls for him almost on sight, but of course her situation is desperate and there are sound Darwinian reasons for choosing a healthy, strong mate when you are unable to provide for yourself and your child. He looks like shelter from the poverty and hopelessness of 1952.

For the boy (Misha Philipchuk), it is a little more complicated. He often has visions of his real father, who died before he was born but speaks to him and promises to return soon. Yet all little boys are impressed by soldiers, and when Tolyan (Vladimir Mashkov) asks Sanya to look after his revolver, the boys eyes grow as wide as saucers. Soon the three are living together as a family, and the boy enters into an uneasy mixture of fear, respect and love for the man.

Tolyan, it is true, is a charmer. He is popular in the series of boarding houses where they take a room, or part of a flat, and meals are often communal affairs fueled by vodka. He likes to propose toasts to Stalin and encourage the others to get drunk, and then steal into their apartments. It is not unknown for the mother and boy to get urgent messages to meet him, immediately, at the train station, and they live a nomadic existence. The army uniform and Tolyan’s ability to bluff are protections against identify checks and police questions. So are his “wife” and “son.” The movie proceeds on two fronts. We gradually learn more about the real nature of Tolyan and his criminal activities, and at the same time the relationships among the three people deepen and grow more complicated. Sanya in particular is conflicted. He indulges the fantasy that his real father will return. He resents Tolyan for being a fake, a thief and a philanderer. And yet he admires him, too, and feels both shame and pride when the man uses him to squeeze through a small window and open a flat to be burgled.

Behind, beneath, around everything is the everyday reality of life in Stalin’s Russia. The most touching sequence in the movie shows a transfer of prisoners from a district prison to transport that will take them to Siberia. Their friends and relatives wait in the snow for a glimpse of them. The prisoners are released from jail and sent running down a gauntlet of men and dogs, as their loved ones shout out desperate messages.

Did ordinary Russians think of Stalin the way Sanya thinks of Tolyan? As a big, bluff provider who would protect them–as a liar and a thief, but not without charm? That is the implication lurking in every frame of “The Thief,” but the movie works because it doesn’t insist on the parallels. And the final sequence, of disillusionment and betrayal, is the saddest, because in it Tolyan is finally reduced to telling the truth.