It all comes down to a missing pistol.

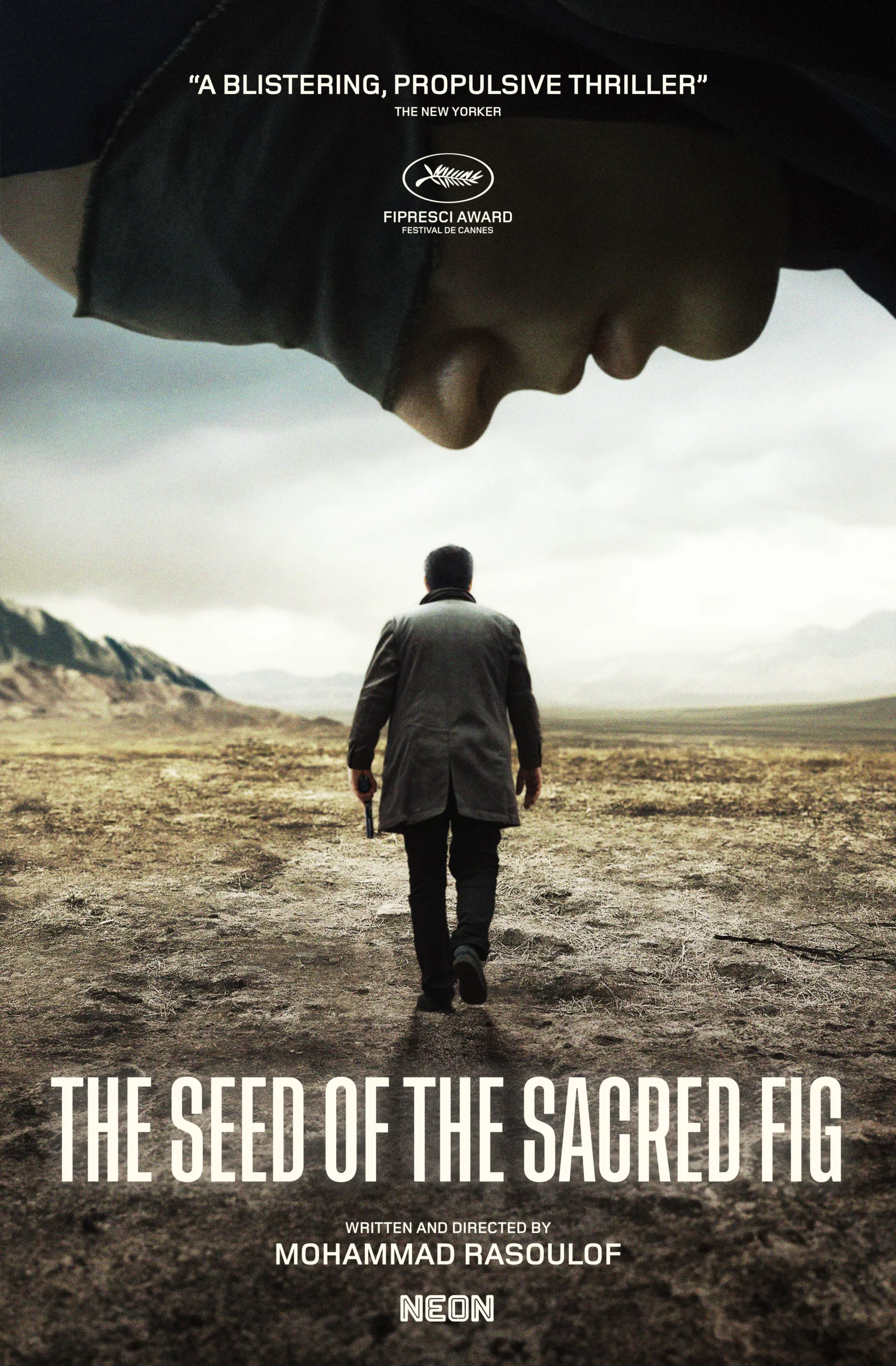

It’s almost exactly halfway through Mohammad Rasoulof’s powerful, angry, masterfully crafted “The Seed of the Sacred Fig” that Iman (Missagh Zareh) realizes that he can’t find the gun. But it has figured into the drama from the beginning. Iman is a true believer in the values and laws of the Islamic Republic, and when the story opens, he has just received a promotion. He has been made an investigator, a position just below a judgeship, the job he really craves. And with the position comes a pistol.

The weapon is for protection, he is told. There may be numerous dissidents in Tehran’s streets who would like to take out one of the theocracy’s key functionaries. The gun also symbolizes his new place in a brutal hierarchy where he has the power of life and death over people he’s never met; he soon learns that prosecutors will ask him to sign off on the death sentences of accused folk whose guilt he’s not actually investigated.

“The Seed of the Scared Fig” is the latest from one of two filmmakers (the other is Rasoulof’s friend Jafar Panahi) who have dominated Iranian cinema and its place in world forums for the last decade-plus with films that have been made illicitly and smuggled out of the country to foreign festivals and art houses. Their films are searing, if sometimes wittily indirect, indictments of the Islamic system and all it stands for.

The new film is Rasoulof’s grandest broadside against the regime so far, and it may be the last he can make in Iran. Like his other films, it was shot secretly, without official sanction. But near its completion, he was hit with the most severe of the several prison sentences (eight years, with flogging) that have come his way, a signal that remaining and working in Iran was no longer an option.

But leaving was not a simple matter. The film’s legend now contains the story of the harrowing, nearly one-month secret journey Rasoulof was forced to take to escape Iran, an ordeal that ended when he was granted asylum in Germany, where his daughter lives and where he was able to finish the film’s post-production.

The film arrived in Cannes in time to be one of the most highly anticipated features in the official competition. During the festival, some press reports described “The Seed of the Sacred Fig” as the odds-on favorite to win the Palme d’Or. That it didn’t win that prize (which went to Sean Baker’s “Anora”) but rather a special jury prize must have been a keen disappointment to Rasoulof, since the film seems precision-tooled to embarrass the regime in Tehran by winning as many top accolades as the world has to offer.

Context is crucial to the story it tells, and the message it wants to send the world. Iman receives his promotion very shortly before the “Woman Life Freedom” movement sweeps Iran in September 2022, following the in-custody death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who had been picked up for wearing her hijab improperly. However, these events impact Iman’s home life sooner than they do his professional duties.

Most of the film’s first half, in fact, focuses on Iman’s family: wife Najmeh (Sohelia Golestani) and teenage daughters Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki). It should be noted here that these three actresses performed in the film’s home scenes without wearing hijab, a courageous move that could put their careers in danger. (Iranian regulations since the Revolution have dictated that women wear hijab in all scenes, including ones at home when most women would doff their head covering.)

When we first see the family, it seems full of ordinary tensions and disconnects. The girls pay little attention to work-preoccupied Dad, and he reciprocates in kind. Mom is the mediating go-between, and her role becomes more delicate and important when Iman gets his promotion. He conveys his nervousness and worry at work to her, and she lets the girls know that they must be increasingly careful about everything: what they wear and say in public, who they associate with, and, perhaps especially, what they post on social media.

The news of Mahsa Amini’s death comes as a shock. Iman, echoing Iran’s equivalent of Fox News, says the girl evidently had a stroke. But Rezvan and Sana don’t believe it for a second. One night when the family is having dinner and the TV is on, broadcasting the official news, Rezvan snarls, “Lies, all lies,” and Iman explodes at her. No more TV at dinner. But that hardly dampens the fury that is increasingly playing out in Tehran’s streets.

Rasoulof shows this gradually through the rest of the film in clips of cell phone videos of the actual events, which are surely more powerful than staged scenes would be. We see young people running through the city, pursued by the riot police, the hijab of many women thrown aside; and then there are bodies in the streets, scarlet rivulets of blood creasing the pavement beside them.

Rasoulof gets terrific performances from all of his cast, but particularly noteworthy is Sohelia Golestani’s work as Najmeh, which captures the woman’s subtle, gradual transition from defender of her husband to an ally of her daughters. In one of the film’s most affecting scenes, a young woman named Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi), a college friend of Rezvan, comes to the apartment having been wounded in the riots, one side of her face bloody and full of buckshot. Najmeh painstakingly removes the buckshot and dumps them in the sink along with a lot of blood – a haunting image.

Missagh Zareh is also excellent as Iman, a man who is violently alienated from his family not only by what is happening in the streets of Iran but by the whole world they inhabit. Sana wants to dye her hair blue? Najmeh tries to explain, essentially, it’s what the kids today are into. But his only reaction is, “It’s against God,” which he truly believes.

After the pistol vanishes, an increasingly desperate search for it is mounted, one that disrupts the family even as it jeopardizes Iman’s place at work. And in its last quarter, the film turns into an out and out thriller, one that takes the family on a road trip to Iman’s home village even as the question of the missing pistol remains provocatively open.

This last section is undeniably enthralling–Rasoulof stages it with breathtaking skill–and the film’s final image plays like a rallying cry for the overthrow of the patriarchy. But I’m afraid I found it more simplistic than Iran’s current situation calls for. The last time I was in Iran, in April of 2018, two of the country’s most prominent directors confidently predicted that the regime would fall by year’s end. I understand and sympathize with that wishfulness, but I don’t think it–or any movie based on it–is likely to topple such a deeply entrenched and fiercely protective regime. Perhaps movies are not made for such tasks, even if we agree with their heartfelt aims.