The pandemic has been a time of missed connections. That’s “missed” in both senses of the word, as in “the receiver missed the football” and as in the longing we feel for the people and places and times of our live that are most dear to us.

As the all-too-familiar Zoom call opening of “The Same Storm” shows, we have all struggled to connect online, coaxing our dear and not-so-near on un-muting themselves and positioning the camera. And as we see throughout, we all miss the closest connections, those now separated by social distance and those even more wrenching separations by the universal complications of family life. We may know better, but we can’t help feeling that if we could just get them to see how right we are, everyone would do what we want them to.

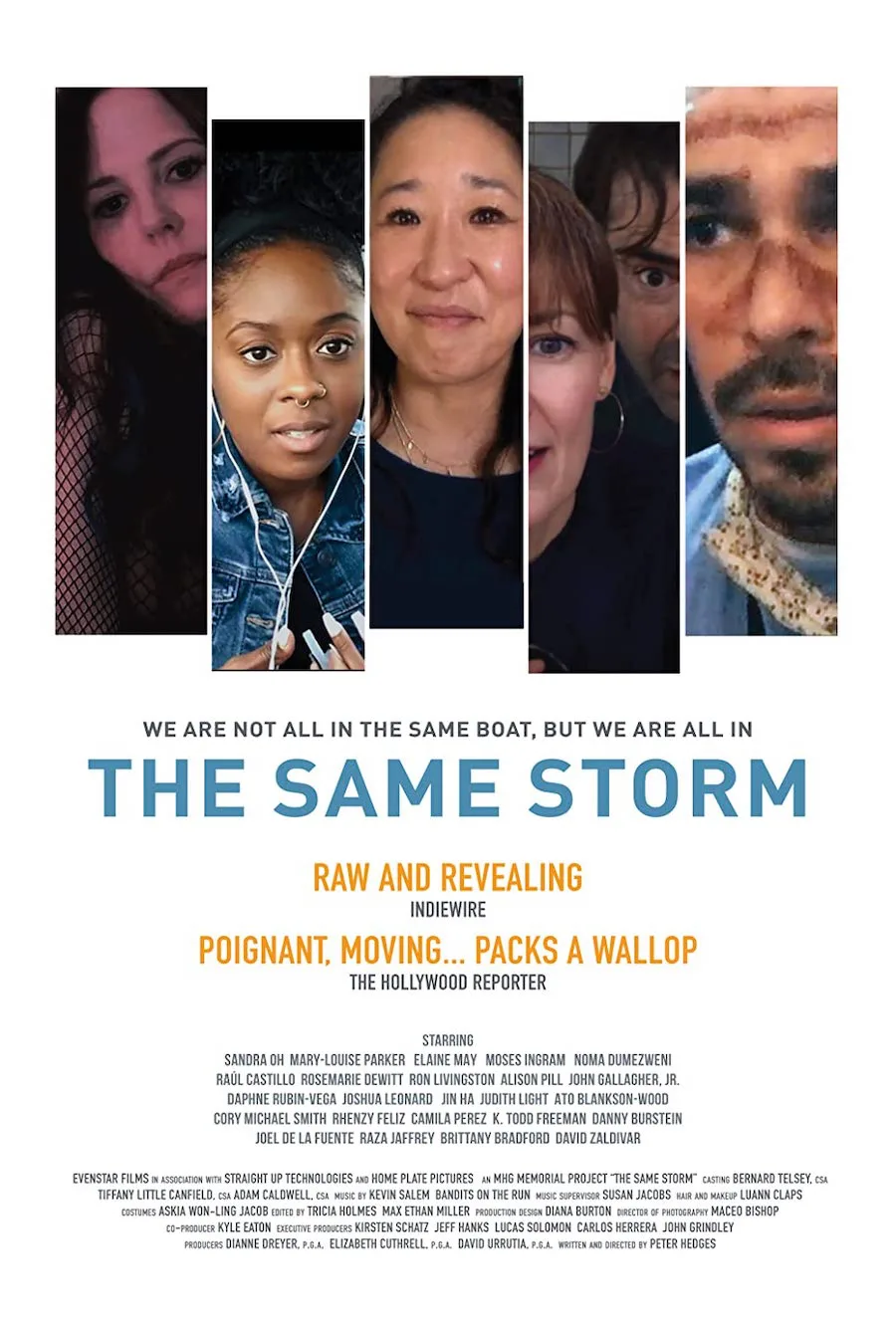

That opening Zoom call is like hearing a symphony orchestra tune up before the concert. “Can you see me?” A group of actors are assembling for the first time. There are comments about the “intimacy” of peeking into each other’s homes, some questions about how best to create the environment for the characters they are creating. And then a clapperboard snaps shut to start the scene and the story begins with a quote from Damian Barr that gives the film its title: “We are not all in the same boat. We are all in the same storm.”

That storm, of course, is the pandemic, and “The Same Storm” gives us a series of linked stories, with a character from each online call leading us into the next. While some earlier efforts at pandemic filmmaking have seemed like awkward work-arounds, even stunt-ish, writer/director Peter Hedges has transcended the structural limits to make a film that is organic, with characters that extend beyond the corners of their FaceTime and Zoom boxes.

We see the passage of time through milestones observed online, both personal and political. A wife learns that her husband in the hospital with COVID is suddenly in critical condition, and the best the nurse can offer is to write down on what he calls “the iPad, the goodbye pad” whatever last message she wants him to hear. There is a bittersweet birthday gathering of four adult children and their ailing mother. Another family holds a Zoom funeral. Parents waiting out the pandemic in the country check in on their adult children at home in the city. A father begs his daughter not to go to a Black Lives Matter rally where there may be violence. A sex worker promises her client, an exhausted male nurse, that she will join the nightly pot-and-pan-bangers paying tribute to essential workers in his honor.

All of these encounters face heart-wrenching frustrations. It is not coincidental that so many of the characters are professional caregivers—two doctors, a health care aide, a nurse, an elementary school teacher, a sex worker who provides comfort in her own way, a policeman whose job is to protect and serve. It is particularly poignant to see these many of these people both in their professional lives, maintaining some professional distance, or trying to, and then when we see them lose that distance as they struggle with their own families or with their own choices.

Hedges has a gift for bringing us into the lives of characters in even the briefest sketches with the strong support of an outstanding cast. It is a joy to see veterans like Elaine May, Sandra Oh, and Judith Light as three very different mothers fully inhabiting their roles with such immediacy and precision. Seeing so many of them at work and with family or a support group grounds the film by giving them dimensionality. Oh is especially affecting as a very concerned mother in one scene and then as a participant in an AA meeting in another. We first see a home health care aide (Daphne Rubin-Vega, another stand-out) as a concerned professional, calling in a doctor for a reluctant woman showing signs of COVID. Seeing her then very worried about her own family member, speaking in her first language, gives her character an authenticity far beyond what we might expect from her brief screen time.

Bridget (Alison Pill) is a teacher trying to do her best with remote learning. Rosemary DeWitt and Ron Livingston are parents trying to act as breadwinner, babysitter, tutor, home school facilitator, and playdate all at once. They talk to Bridget about their son over Zoom. “Keeping them engaged seems like a win,” she tells the exhausted parents, as she explains an assignment to write about what her students are experiencing. And the parents learn through their son’s school essay that they have not been as effective at protecting him from the pressures of the shutdown as they had hoped. Then we see Bridget with her three brothers, trying to protect their ailing mother (Light) from her children’s painful arguments about politics.

Throughout the film there are parents worried about children and children worried about parents, the physical and technological distance only a small part of the gulf that too often separates us from what we wish we could heal. In the movie’s most heartbreaking scene, Oh understands a moment before we do that her son (a superb Jin Ha) is in severe distress. She tries to be reassuring and calm, but her eyes reveal her panic and devastation. The most transactional interaction is between a sex worker and a client who just wants an escape from his work at a hospital. They abandon anonymity and make a brief but genuine connection. This provides context and balance for the scenes where a character refuses to or is unable to engage. As fragile and complicated and frustrating as the efforts are, they are vital, they are meaningful, and they are sustaining.

A character we see only briefly in the film says that there are only two kinds of love, too much and too little. On reflection, he says, he has learned that “too much” is his favorite kind. “The Same Storm” brims with that kind of love. It may be too much to protect us from the pain of missing connections, but it is enough to remind us that it is not just the storm that connects us, but the ability to tell our stories and see ourselves reflected in the stories we see.

Now playing in theaters.