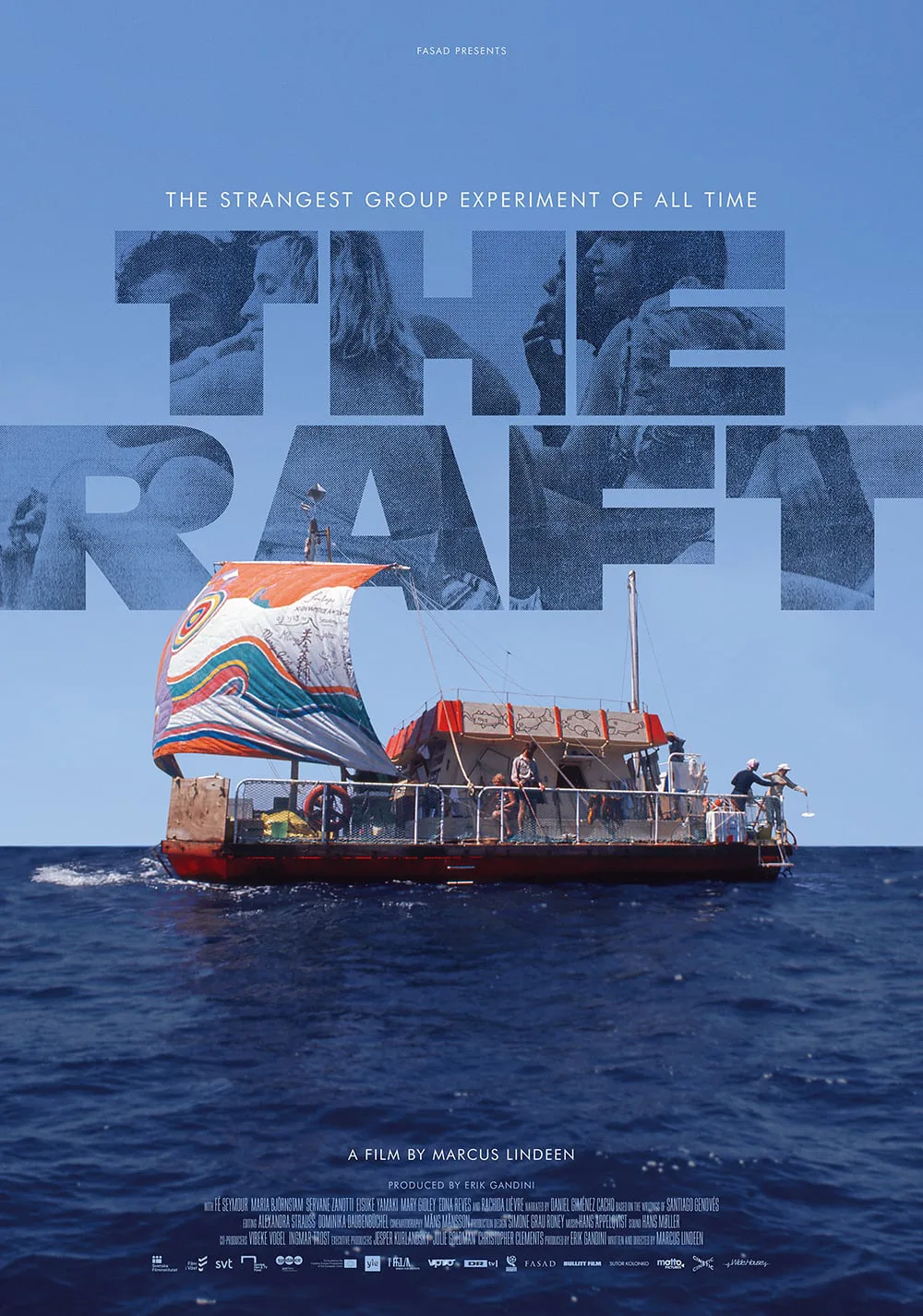

In the summer of 1973, 11 strangers boarded the Acali, a bulky, ship-sized raft, and left on a trans-Atlantic journey from the Canary Islands to Mexico. Their goal: to study human aggression in hopes of preventing future wars. At least, that was the stated goal of Santiago Genoves, the study’s organizer and ostensible leader. One of the main pleasures of watching “The Raft,” a new documentary that combines decades-old footage of the Acali‘s 101-day voyage with modern-day commentary by the ship’s six surviving crew mates, is that the Acali‘s story isn’t just told from Genoves’s self-mythologizing perspective.

That’s also one of the most frustrating things about “The Raft”: director Marcus Lindeen seems to let the six surviving members of Genoves’ experiment tell their stories in their own respective ways. It sounds great (and sometimes is), but Lindeen’s hands-off approach—he mostly lets the Acalians interrogate each other—starts to wear thin whenever his subjects try to explain their complex feelings of resentment, skepticism, and nostalgia about what happened during the Acali‘s journey. There’s consequently a weird circular logic to Lindeen’s presentation: he seems reluctant to super-impose an artificial narrative onto the group’s experiences—since Genoves already tried and failed to do that in his journals and notes—but he doesn’t ask his subjects enough follow-up questions to get worthwhile, memorable answers from them. In “The Raft,” less authorial control doesn’t necessarily make for a better story.

Lindeen must organize and comment on his subjects’ experiences, if only for the sake of establishing a timeline of events. He invites the six surviving Acali crew members (minus the late Genoves, whose thoughts are narrated by Mexican actor Daniel Giménez Cacho) to gather and talk inside a life-sized replica of the ship. Lindeen’s subjects are generally mild-mannered, but tension inevitably arises whenever they talk about Genoves. Some Acalites are still uncomfortable with Reves’ demands of them, especially his obsession with making his subjects pair off and have sex, ostensibly for scientific purposes (in his notes, Genoves admits that he sought out “sexually attractive” participants). Alaskan engineer Fe Seymour remembers that Genoves wanted her and Catholic priest Bernardo (now deceased) to have sex just because they are both black.

Lindeen obviously has a low opinion of Genoves based on edited selections from Genoves’ posthumously narrated writings: over the course of the Acali’s 101-day tour, Genoves became the kind of toxically aggressive personality that he set out to study. There are blatant undercurrents of passive-aggression in his notes about the trip’s inconclusive results (“Instead of supporting me, they behave like a bunch of little children”). Genoves’ frustration was also noticed and is guardedly commented upon by the Acali’s survivors, most of whom have adopted a live-and-let-live attitude.

Seymour and her peers are obviously not wrong to feel the way that they feel now. But that doesn’t mean that their experiences and recollections are necessarily interesting. Lindeen generally doesn’t do enough to shape his subjects’ experiences into a compelling narrative. He seems to want to keep the story of “The Raft” more open-ended, though he never gives viewers enough information so that we can make up our own minds. Apparently, all the Acalian women thought Uruguayan anthropologist Jose-Maria was the most handsome man aboard the ship—but so what? Some women also admit that they either tried or discreetly had sex on the Acali. Ok, and … ? Lindeen seems to be as skittish as his subjects, possibly because the Acali was repeatedly referred to as a “sex raft” in international news coverage. To be fair: it was a raft and Genoves did encourage his crew to have sex and then fight about it.

Still the success of “The Raft” is also not entirely dependent on its creators’ intentions. I was especially taken with scenes where Seymour’s crew-mates realizes that their experiences on the Acali differed from hers because they’re not black. I also love a scene where Fe admits that she fantasized about killing Genoves with the help of her fellow cast-mates. Japanese photographer Eisuke Yamaki seems to speak for his group—or, at least, for American waitress Mary Gidley, who turns mayo-white as Seymour describes her gruesome murder fantasy—when he says: “What was great with our group is that we didn’t do that.”