“The Prince of Pennsylvania” represents a kind of film that has become lamentably popular in recent years. It forces realistic characters into an absurd plot, and expects us to accept the plot because we believe in the characters. The paradox here is obvious: If the characters are as real as they seem, they should be smart enough to recognize that their lives are manipulated fictions. When I see a convincing, three-dimensional human being doing something in a movie that is obviously artificial and silly, I wonder why he doesn’t simply tell the screenwriter to shove his screenplay where the sun don’t shine.

Look at the plot of this movie. It takes place in a real town, with real people, who have real problems. And it ends with a scene that depends on a security guard not being able to tell a human voice from a voice on one of those little tape recorders you can fit in your pocket.

Show me that security guard and I’ll believe the story. Not before. Am I being too logical here? Too hard-boiled? Not if you expect me to believe the rest of the story, which involves a small-town coal miner, his family, and the woman who runs the hot dog stand on the edge of town.

See what I mean? The people in this movie are gritty, hard-edged, plausible people. They work for a living. They’ve been around the track a few times. It is wrong to put them in a plot that depends on the kind of yo-yo plot gimmick you’d expect in a Saturday morning cartoon. The whole last act of this movie generates one groan after another, because the characters have lost their bearings, cast off from their moorings in the real world, and gone adrift in the deep waters of an Idiot Plot.

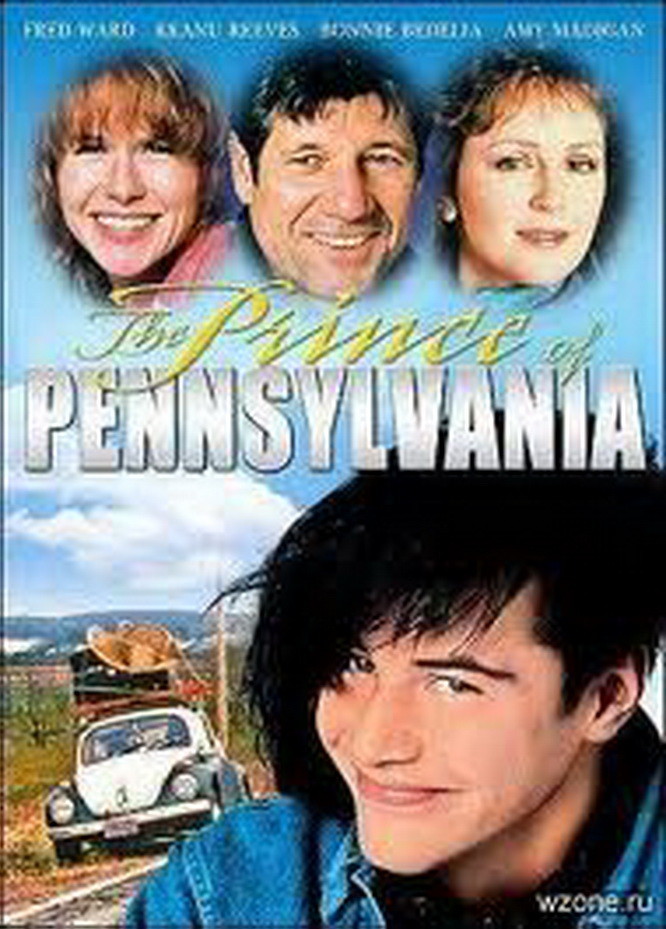

That’s too bad, because I like the characters. The movie involves a coal miner (Fred Ward) who has an unrealistic, romantic view of life. He pictures himself as the king of Pennsylvania, his wife as the queen, and their son as the prince who will someday inherit the kingdom. The wife (Bonnie Bedelia) is restless under his benevolent tyranny, and eventually drifts into the arms of Ward’s best friend.

Their affair takes place in a trailer that was once her father’s home, and it’s there that her son (Keanu Reeves) discovers them one day.

This is just more information for him to file away. He’s a loner at high school, he doesn’t fit in, and the last thing he wants to do is follow his dad down into the mine. His role model is a woman from the 1960s (Amy Madigan) who is still a half-baked hippie, and runs a broken-down drive-in. Business is not the first thing on her mind. She smokes a lot of dope, does a little dealing on the side, and wishes she could break loose from her affair with a local cop. Their friendship is based on lust. Her relationship with the kid is more idealistic; they talk about music and life, and about how everybody else in the town is an idiot.

Now, then. Given this plot, no matter what you think of it, don’t you imagine it would be possible to construct a movie in which these lives interact in a human way? A way in which no character is forced to violate the rules of the logic by which he lives? The opening scenes of the movie give no hint that the plot is about to take a U-turn into absurdity. But then the son and the drive-in hippie concoct a plan to kidnap the father, hold him for ransom, and use the money to solve their problems.

Their scheme involves the girl sneaking into the mine shaft by an abandoned tunnel. In the mine, the father and son will be working the same two-man shift. They’ll tie up the father, and then the girl will pretend to “be” him to fool the security guard who checks out the workers at the mine head. How will she fool him? By holding her head down, looking the other way, and playing a tape recording of the father’s voice.

Give me a great big break. The entire notion is brainless.

Worse, it bogs the movie down in a contrived sitcom plot in which everybody is assigned ironic one-liners, and the audience is supposed to laugh on cue as if they had no more brains than the average television hero. I was dismayed, but I was also disappointed, because I had grown intrigued by the characters – especially Madigan’s unreconstructed hippie, a woman with a lot of specific and believable details about her. A movie about her would have been interesting. A movie about any of these people might have had a chance, if the filmmakers had retained a shred of sanity.