The makers of “The Possession of Hannah Grace” clearly intended for it to be dark. After all, it’s about an exorcism that goes horribly wrong, resulting in further mayhem months later at a morgue. But they probably didn’t mean for it to be visually inscrutable, which is what this quick and dirty—and mostly scare-free—horror film ends up being.

Dutch director Diederik Van Rooijen’s movie mostly takes place in the middle of the night at a hospital, a brutalist monolith that radiates doom and gloom. (The exterior is actually the Boston City Hall building, transformed slightly with a bit of signage.) Once inside, though, everything else is dark too: the lobby, the hallways, the women’s bathroom and especially the morgue. Van Rooijen and screenwriter Brian Sieve actually use that room’s lighting as a vaguely intriguing plot point: It operates on motion sensors, turning on with a clickclickclick and an ominous buzz whenever someone enters. (The overhead lamps also happen to be shaped like a cross, in a not-so-subtle bit of symbolism.)

Surely, this was an aesthetic choice—an attempt to create an unsettling mood. But more often than not, it’s just plain difficult to see what’s going on, and that murkiness results in an overall feeling of frustration. It certainly doesn’t help that “The Possession of Hannah Grace” is one-note in its foreboding tone, punctuated by the occasional jump scare.

“Hannah Grace” begins with the title character (Kirby Johnson) undergoing a pretty standard movie exorcism. She’s tied to a bed with priests standing over her, praying and splashing her with holy water. The devil inside causes her to writhe and contort while spewing vile things. Seeing the carnage and chaos she’s causing, her dad (Louis Herthum) eventually says screw it, takes control of the situation and smothers her face with a pillow.

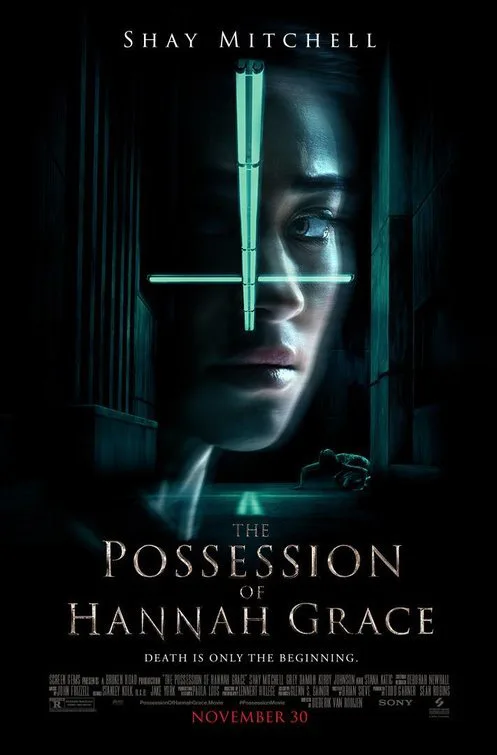

This is where most movies about demonic possession might end; here, it’s just the start. Because three months later, Hannah’s body turns up at the morgue on what just happens to be the first night of work for Megan (Shay Mitchell of “Pretty Little Liars”), a new intake assistant. The stoic Megan is a former cop battling demons and substance abuse issues; newly clean, she hopes for a fresh start at … the morgue. This is basically all we know about this character, who’s at the center of the film. (In order to secure the job, though, she insists in a winking bit of foreshadowing: “I believe when you die, you die. End of story.”) We know even less about the young woman who gives the film its title and serves as its driving narrative force.

Anyway, Megan tries to run through all the steps she’s just learned as far as photographing and fingerprinting the body before placing it in storage, but Hannah Grace’s overwhelming evil—even in cold corpse form—throws everything out of whack. In no time, she’s sneaking out of her drawer when no one’s looking and wreaking havoc on the few employees who have the misfortune of being on duty during the graveyard shift. This central premise is the only compelling element of Sieve’s script, but it’s executed in dreary fashion.

Part of the problem is that the rules are unclear. Sometimes Hannah Grace crawls in a crablike way, her mangled and bony body making a crackcrackcrack noise with every jumpy movement. (The sound design is indeed creepy the first time around with all these auditory tricks, but quickly grows repetitive.) Sometimes, she walks upright. Sometimes, she leaps forward or skitters up a wall. She can interfere with cell phone signals and power lines and move entire ambulances with just a slight shove but wastes her time hanging around the hospital—and waits to inflict her wrath on Megan until the end.

We’d have no movie otherwise—and as is, “Hannah Grace” is barely 85 minutes, with an ending so abrupt that you’ll wonder whether you’ve missed something. (Spoiler alert: you haven’t.) But maybe we’d actually be able to see what’s going on in the outside world.