“The Night They Raided Minsky’s” is being promoted as some sort of laff-a-minit, slapstick extravaganza, but it isn’t.

It has the courage to try for more than that and just about succeeds. It avoids the phony glamour and romanticism that the movies usually use to smother burlesque (as in “Gypsy”) and it really seems to understand this most-American art form.

Burlesque was born and thrived at a time when America was engaged in the early stages of the current moral revolution, when the rural Puritan ethic and the tentative “sophistication” of the cities discovered each other. Burlesque was essentially vaudeville plus sex, and in the early days the sex was direct, naive and almost innocent.

Director William Friedkin presents exactly that period, when there was an exuberance and healthy, robust quality burlesque later, dismally, lost. And he has placed his film solidly inside the Lower East Side society that produced Harold Minsky’s burlesque. His characters live a public, voluble life, inhabiting delicatessens (and eating incredible, hilariously photographed meals). They dream up the sort of persecution of vice detectives that Ben Hecht was recording in Chicago. They regard burlesque not so much as an occupation, more a way of life.

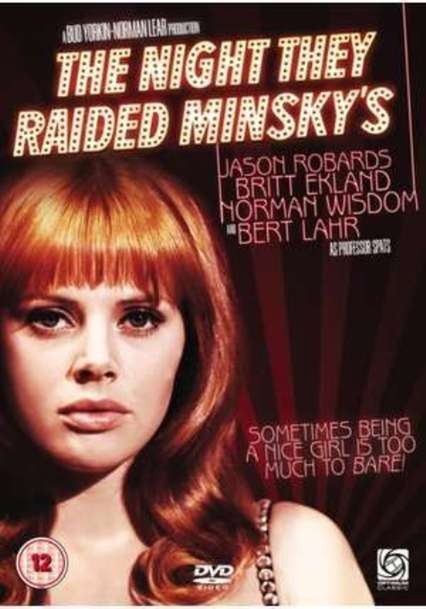

The story concerns a young Amish girl (Britt Ekland) who comes to the big city and is blinded, as they say, by the glittering marquees. She dreams of dancing at Minsky’s. She is contested for by two comics (Norman Wisdom and Jason Robards); pursued by her bearded, fundamentalist father, and she accidentally, inadvertently and charmingly invents the striptease.

Friedkin has deliberately used stereotypes in casting. Miss Ekland is as wide-eyed and innocent as anyone since the young Debbie Reynolds and her father is a refugee from a morality play. So the story itself takes on some of the simplicity of the burlesque skits which liberally illustrate the action.

Norman Wisdom, the great British comedian and music-hall veteran, is very good as the tenderhearted comic; Jason Robards isn’t quite so good as the straight man and big operator. Bert Lahr is present just enough to make us mourn his recent death, and the film’s last scene is a touching farewell.