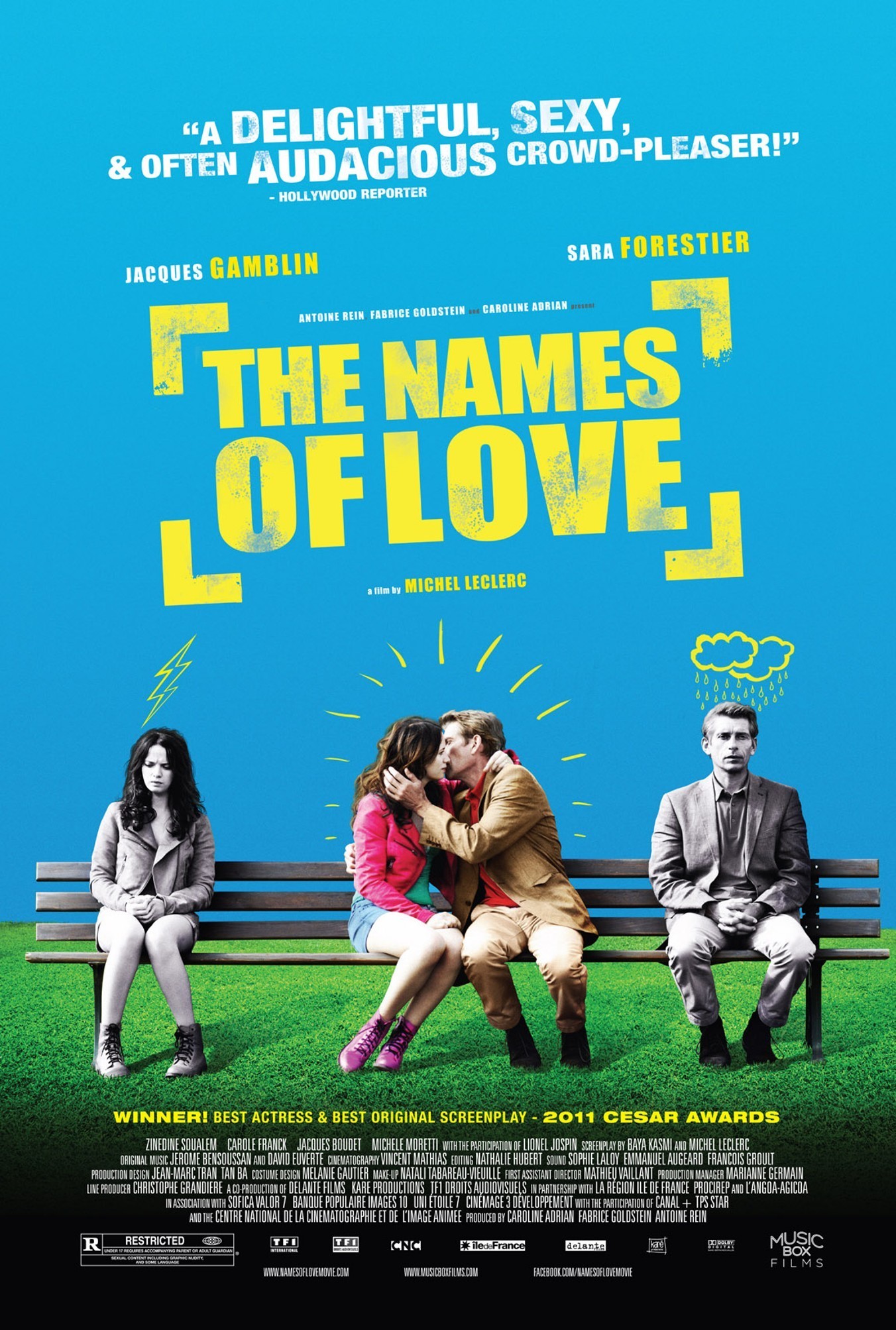

If more fascists slept with Baya Benmahmoud, there would be fewer fascists. That is her theory, anyway, and a good many fascists allow her to test it during “The Names of Love,” a wacky French satire about the supercharged political climate in France. Baya (Sara Forestier) is the child of a gentle Algerian father and a fervently political French mother. Sexual abuse by her childhood piano teacher has inspired her, somewhat obscurely, to use sex as a weapon of political persuasion.

“The Names of Love” swims in the waters of French politics, which are a good deal more diverse than our own, spanning communists on the left and neo-fascists on the right. The Socialist Party of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, in this company, is close to the center. Baya’s evangelical recruitment is further eased by her freedom in defining “fascist,” which for her seems to embrace anyone even slightly shy of the activist left.

The movie centers on her love affair with Arthur Martin (Jacques Gamblin), a studious specialist in the diseases of birds. She meets him after breaking into a talk show he’s on. After a first sexual encounter leads nowhere, she breaks the news to him: She always sleeps with men on a first date. Furthermore, as a sincere Socialist, he is not quite left-wing enough for her tastes.

Their star-crossed affair develops in an ingenious story structure by director Michel Leclerc and his co-writer, Baya Kasmi. We meet Baya and Arthur as children, and then in (adult) voiceovers, they explain their ancestral backgrounds. These children rematerialize from time to time to discuss developments with their adult selves. Arthur’s Jewish mother, Annette (Michele Moretti), escaped the Holocaust, which claimed her family, by being hidden under a non-Jewish name in an orphanage. Neither Arthur nor his Catholic father, Lucien (Jacques Boudet), ever, ever, reveal her Jewish background — not even to Arthur, who has apparently been named after a popular brand of washing machines.

Baya’s father, Mohamed (Zinedine Soualem), is a non-religious Algerian immigrant who is a brilliant artist but too modest to admit it; he works as a paid and sometimes voluntary Mr. Fix-It who is forever setting things right again. Her mother, Cecile (Carole Franck), grew up as a French leftist and married Mohamed in part out of political conviction of a milder sort than that adopted by her daughter.

So we have a hero who doesn’t “seem” half Jewish, and a heroine who doesn’t “seem” half Arab, engaged in a love affair that brings them and their parents into contact with the past. Sometimes this leads to dark humor. Arthur, for example, is reluctant to introduce Baya to his parents because talking with his mother is like tip-toeing on eggshells. She’s so sensitive that any reference to her past is likely to inspire anxiety and despair. When Arthur and Baya finally do have a meal with the Martins, Baya is warned to make no reference whatever to anything remotely suggesting the Holocaust, and of course her subconscious mercilessly generates such words as “oven” and “camp.”

This scene is funny in concept but not so funny in execution. That’s sort of the whole story of “The Names of Love.” We see it’s a comedy, we appreciate the satire, but our laughter is easily contained. What I admired was the story of these characters themselves. What an odd couple. An intent scientist and a wild child half his age. A straight arrow and a sexual predator. A neatly buttoned-up man and a woman whose blouses and sweaters have a way of spontaneously revealing her breasts.

So free is Baya with her body, indeed, that after receiving an urgent phone call, she pauses long enough to put on her shoes but neglects to put on anything else before rushing out into Paris and onto the Metro completely nude. This results in a predictable scene of a Muslim couple being offended; it might have been funnier if a couple her age had said “far out!” in calling her attention to her undress.

Sara Forestier is uninhibited in the role and has great comic energy. She won the Cesar for best actress for this performance. She makes a good contrast with Jacques Gamblin’s dutiful, responsible Arthur. What a fate, to be separated from his real name and given the name of a washing machine. Imagine an American named Facebook Martin. I enjoyed this film. I know I was intended to laugh more. It didn’t bother me that I didn’t.