The West Indies were a footnote to the British Empire, and the Indian community of Trinidad was a footnote to the footnote. After slavery was abolished and the Caribbean still needed cheap labor, thousands of Indians were brought from one corner of the Empire to another to supply it. They formed an insular community, treasuring traditional Hindu customs, importing their dress styles and recipes, recreating India far from home on an island where it seemed irrelevant to white colonial rulers and the black majority.

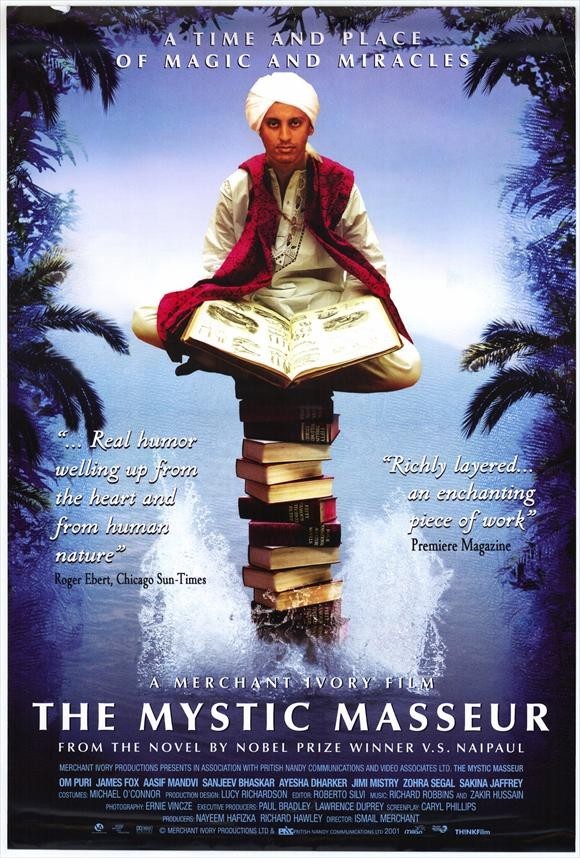

“The Mystic Masseur” is a wry, affectionate delight, a human comedy about a man who thinks he has had greatness thrust upon him when in fact he has merely thrust himself in the general direction of greatness. It tells the story of Ganesh, a schoolteacher with an exaggerated awe for books, who is inspired by a dotty Englishman to write some of his own. Abandoning the city for a rural backwater, he begins to compose short philosophical tomes, which, published by the local printer on a foot-powered flat-bed press, give him a not quite deserved reputation for profundity.

If Ganesh allowed his success to go to his head, he would be insufferable. Instead, he is played by Aasif Mandvi as a man so sincere he really does believe in his mission. Does he have the power to cure with his touch, and advise troubled people on their lives? Many think he does, and soon he has become married to the pretty daughter of a canny businessman, who runs taxis from the city to bring believers to Ganesh’s rural retreat.

There is rich humor in the love-hate relationship many Indians have with their customs, which they leaven with a decided streak of practicality. In no area is this more true than marriage, as you can see in Mira Nair’s wonderful comedy “Monsoon Wedding.” The events leading up to Ganesh’s marriage to the beautiful Leela (Ayesha Dharker) are hilarious, as the ambitious businessman Ramlogan positions his daughter to capture the rising young star.

Played by the great Indian actor Om Puri with lip-smacking satisfaction, Ramlogan makes sure Ganesh appreciates Leela’s dark-eyed charm, and then demonstrates her learning by producing a large wooden sign she has lettered, with a bright red punctuation mark after every word. “Leela know a lot of punctuation marks,” he boasts proudly, and soon she has Ganesh within her parentheses. The wedding brings a showdown between the two men; custom dictates that the father-in-law must toss bills onto a plate as long as the new husband is still eating his kedgeree, and Ganesh, angered that Ramlogan has stiffed him with the wedding bill, dines slowly.

The humor in “The Mystic Masseur” is generated by Ganesh’s good-hearted willingness to believe in his ideas and destiny, both of which are slight. Like a thrift shop Gandhi, he sits on his veranda writing pamphlets and advising supplicants on health, wealth and marriage. Leela meanwhile quietly takes charge, managing the family business, as Ganesh becomes the best-known Indian on Trinidad. Eventually he forms a Hindu Association, collects some political power, and is elected to parliament, which is the beginning of his end. Transplanted from his rural base to the capital, he finds his party outnumbered by Afro-Caribbeans and condescended to by the British governors; he has traded his stature for a meaningless title, and is correctly seen by other Indians as a stooge.

The masseur’s public career has lasted only from 1943 to 1954. The mistake would be to assign too much significance to Ganesh. His lack of significance is the whole point. He rises to visibility as a home-grown guru, is co-opted by the British colonial government, and by the end of the film is a nonentity shipped safely out of sight to Oxford on a cultural exchange. Critics of the film have criticized Ganesh for being a pointless man leading a marginal life; they don’t sense the anger and hurt seething just below the genial surface of the novel. The young Trinidadian Indian studying at Oxford, who meets Ganesh at the train station in the opening scene, surely represents Naipaul, observing the wreck of a man who loomed large in his childhood.

Movies are rarely about inconsequential characters. They favor characters who are sensational winners or losers. But Ganesh, one senses, is precisely the character Naipaul needed to express his feelings about being an Indian in Trinidad. He has written elsewhere about the peculiarity of being raised in an Indian community thousands of miles from “home,” attempting to reflect a land none of its members had ever seen. The Empire created generations of such displaced communities, not least the British exiles in India, sipping Earl Grey, reading the Times and saluting “God Save the Queen” in blissful oblivion to the world around them.

Ganesh gets about as far as he could get, given the world he was born into, and he is such an innocent that many of his illusions persist. Shown around the Bodleian Library in Oxford by his young guide, the retired statesman looks at the walls of books, and says, “Boy, this the center of the world! Everything begin here, everything lead back to this place.” Naipaul’s whole career would be about his struggle with that theory.