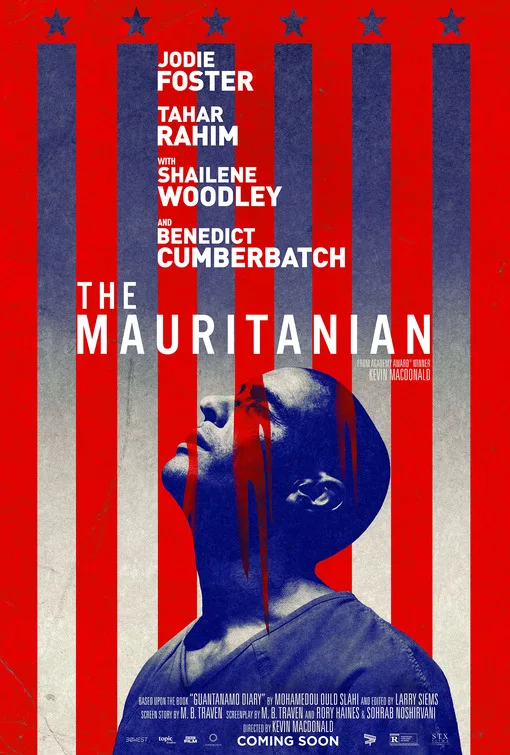

Mohamedou Ould Salahi spent 14 years at Guantanamo Bay despite never being charged with a crime. Picked up shortly after 9/11, he was accused of being one of the key recruiters for the attacks despite almost no evidence that he was directly related. One of the hijackers spent a night on Salahi’s couch, and in the international pursuit of justice, Salahi became another victim. He detailed his imprisonment and torture in a book called Guantanamo Diary, published in 2015, which became a bestseller around the world. A movie was inevitable and now Kevin Macdonald’s version of Salahi’s story, “The Mauritanian,” is here. It is an old-fashioned drama through and through, with some impressive acting from Tahar Rahim, Jodie Foster, and Benedict Cumberbatch. But “The Mauritanian” fails to humanize the story it’s telling, never coming off as something more challenging or interesting than a superficial, manipulative accounting of true events.

“The Mauritanian” opens in November 2001 with the arrest of Salahi (Rahim) but then jumps to 2005, when Nancy Hollander (Foster) agrees to force the government to charge the man with something. As most people know by now, Guantanamo Bay was an essentially lawless place, where people could be held without charges for years, tortured into confessing to something that may not have ever happened. The federal courts have ruled dozens of times that people were held there unlawfully, and the case of Salahi is one of the most high-profile and disturbing. Because of a chance encounter and a phone call from Bin Laden’s phone, Salahi was accused of being the man who recruited people to fly planes into the World Trade Center. With almost no evidence and no charges, they held him for years and Hollander’s cause starts with a simple habeas corpus case, wherein the government would have to charge Salahi or let him go. She recruits an associate named Teri (Shailene Woodley) to assist with the case and begins uncovering more and more dark truths about Guantanamo. On the other side, Lt. Colonel Stuart Couch (Cumberbatch) seeks to defend the government’s case but discovers the depth of his own country’s crimes.

The script by M.B. Traven, Rory Haines, and Sohrab Noshirvani endeavors to make “The Mauritanian” more engaging by playing with its structure, jumping back and forth between ’05 and ’02, when Salahi was tortured, and then Macdonald amplifies that further by playing with aspect ratios. Some of it is effective. Shooting the early interrogation scenes of Salahi in 4:3 amplifies the sense that he’s trapped, boxed in, but it starts to get unnecessary—at one point, Macdonald layers a widescreen present day scene on a flashback one. The characters get lost in the over-direction, which reaches its crescendo during a re-creation of the torture that Salahi endured during the film’s climax, an extended sequence of horrendous violence. It’s notable that what happened to Salahi not be soft-pedaled but it feels showy instead of true.

Worst of all, everyone starts to feel like a device. Salahi is a stand-in for all Guantanamo prisoners; Couch becomes the disillusioned patriot; Hollander is a non-character in such a way that one wonders why we’re spending so much time with her. Perhaps any of these people could have been stronger as the center of the film but they blur into blandness when presented in this context. Macdonald does a good job with his performers—Rahim has always been a great actor and Cumberbatch adds unexpected depth that’s not in the script, particularly as he realizes just what his country has done—but they get lost in the manufactured, dull script, despite their heavy lifting to give it some nuance. The same goes for Foster, who is forced to shuffle papers and read them seriously a few too many times.

In the final scenes of “The Mauritanian,” as in so many true stories, we see footage of the real Salahi, and it becomes clearer than ever that what preceded this wasn’t really his story. Yes, one should only judge the film that’s in front of them, but it’s fair to be critical of a work that doesn’t know what story to tell, and, worse, centers the white saviors of the captured prisoner instead of the prisoner himself. Rahim does so much to make us empathize with Salahi, but seeing the real man smiling and singing reminds one how much the film pushes other narratives into what should have been a deeply human, relatable story instead of another straightforward accounting of a dark chapter in the history of the world. As Macdonald’s film ventures further into its revelations about torture and injustice, Salahi himself gets lost in the storytelling, tragically becoming another face in the crowd of abused prisoners.

Now playing in theaters, and available on VOD in March.