“If you were any thinner,” Stevie tells him, “you wouldn’t exist.” Trevor Reznik weighs 121 pounds and you wince when you look at him. He is a lonely man, disliked at work, up all night, returning needfully to two women who are kind to him: Stevie, a hooker, and Marie, the waitress at the all-night diner out at the airport. “I haven’t slept in a year,” he tells Marie.

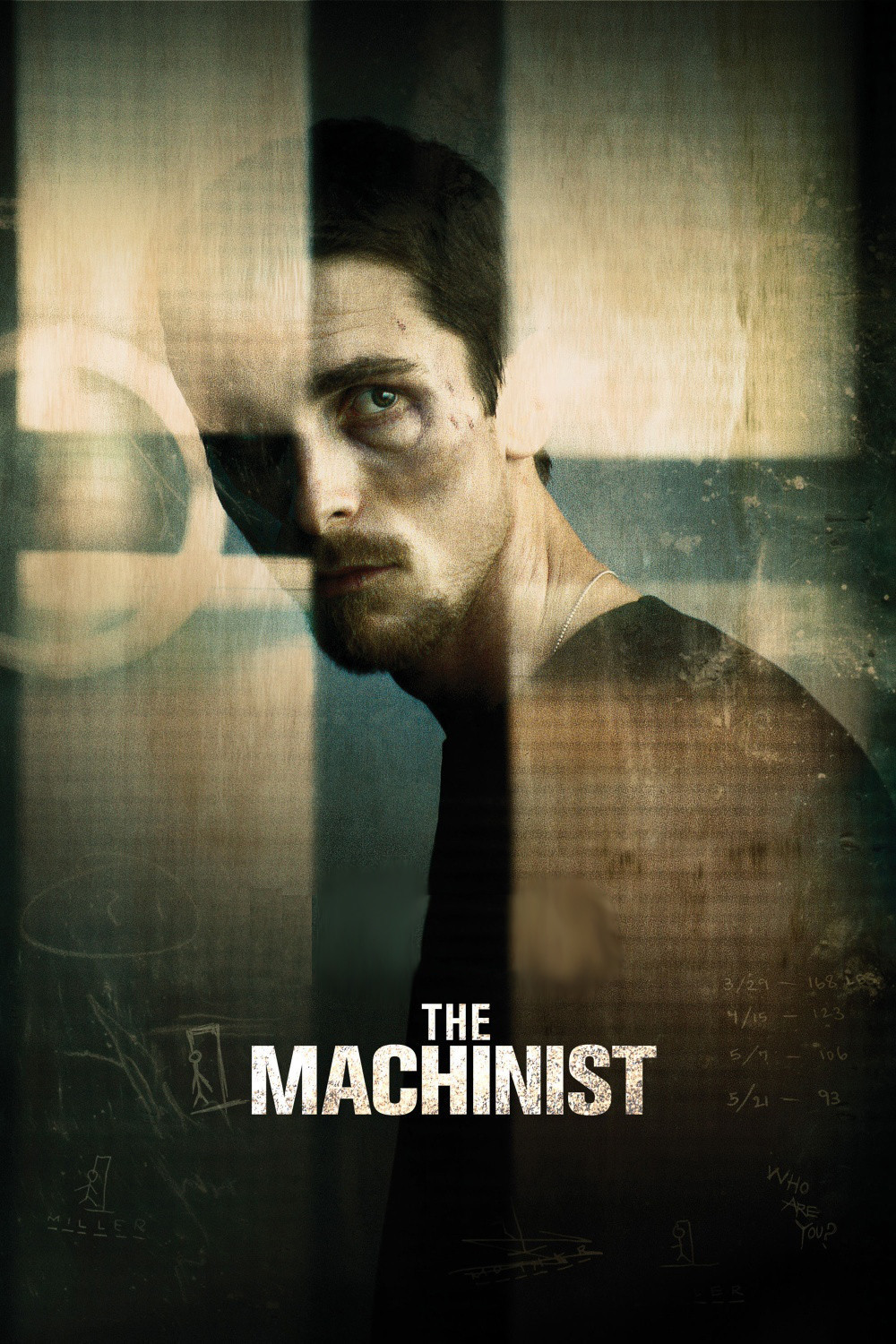

Christian Bale lost more than 60 pounds to play this role, a fact I share not because you need to know how much weight he lost, but because you need to know that it is indeed Christian Bale. He is so gaunt, his face so hollow, he looks nothing like the actor we’re familiar with. There are moments when his appearance even distracts from his performance, because we worry about him. Certainly we believe that the character, Trevor, is at the end of his rope, and I was reminded of Anthony Perkins’ work in Orson Welles’ “The Trial,” another film about a man who finds himself trapped in the vise of the world’s madness.

Trevor works as a machinist. There’s a guy like him in every union shop, a guy who knows all the rules and works according to them and is a pain in the ass about them. His co-workers think he is strange; maybe he frightens them a little. His boss asks for a urine sample. One day he gets distracted and as a result one of his co-workers loses a hand. The victim, Miller (Michael Ironside) almost seems less upset about the accident than Trevor is. But then Trevor has no reserve, no padding; his nerve endings seem exposed to pain and disappointment.

Stevie (Jennifer Jason Leigh) is a consolation. They have sex, yes, but that’s the least of it. She sees his need. Trevor is reading Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot and perhaps there is a parallel between Stevie and Nastassia, Dostoyevsky’s heroine, who is drawn to a self-destructive and dangerous man. Leigh has played a lot of prostitutes in her career, but each one is different because she defines them by how they are needed as well as by what they need.

Marie (Aitana Sanchez-Gijon) is the other side of the coin, a cheerful presence in the middle of the night. “You’re lonely,” she tells Trevor. “When you work graveyard shift as long as I have, you get to know the type.” She wonders why he comes all the way out to the airport just for a cup of coffee and a slice of pie. She wouldn’t mind dating him.

Then there is the matter of Ivan (John Sharian), the distracting and disturbing co-worker who perhaps contributed to the accident. He lost some fingers in a drill press once, and the docs replaced them with his toes. “I can’t shuffle cards like I used to,” he says. Nor, apparently, can he punch in on the time clock: The guys at the shop claim he doesn’t exist. Is Trevor imagining him? And what is the meaning of the Post-It notes that look like an incomplete version of a Hangman puzzle?

“The Machinist” has an ending that provides a satisfactory, or at least a believable, explanation for its mysteries and contradictions. But the movie is not about the plot, and while the conclusion explains Trevor’s anguish, it doesn’t account for it. The director Brad Anderson, working from a screenplay by Scott Kosar, wants to convey a state of mind, and he and Bale do that with disturbing effectiveness. The photography by Xavi Gimenez and Charlie Jiminez is cold slates, blues and grays, the palate of despair. We see Trevor’s world so clearly through his eyes that only gradually does it occur to us that every life is seen through a filter.

We get up in the morning in possession of certain assumptions through which all of our experiences must filter. We cannot be rid of those assumptions, although an evolved person can at least try to take them into account. Most people never question their assumptions, and so reality exists for them as they think it does, whether it does or not. Some assumptions are necessary to make life bearable, such as the assumption that we will not die in the next 10 minutes. Others may lead us, as they lead Trevor, into a bleak solitude. Near the end of the movie, we understand him when he simply says, “I just want to sleep.”