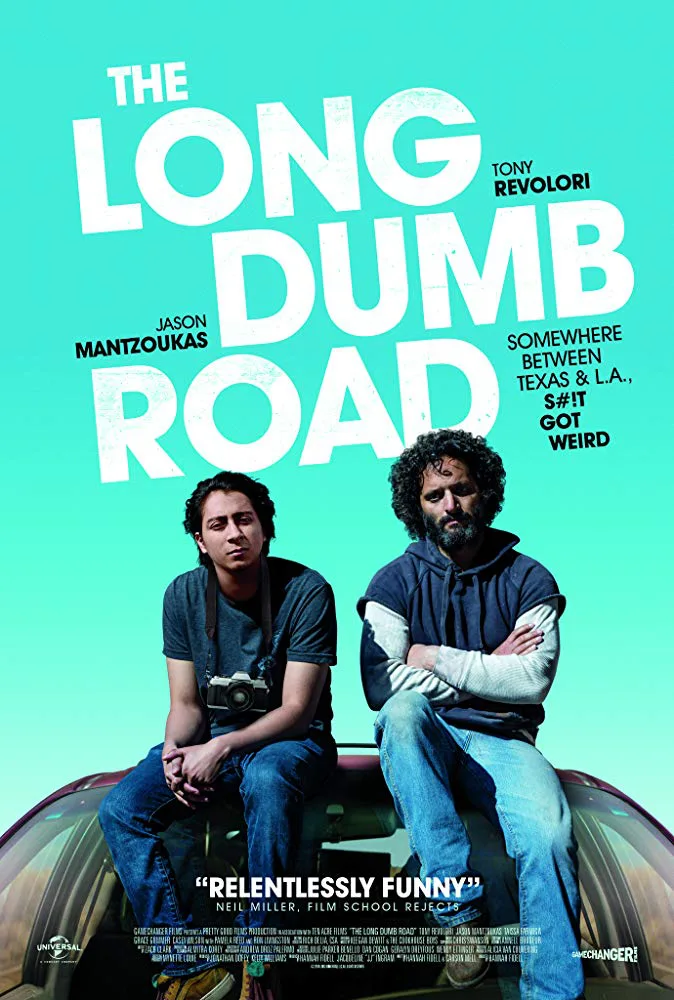

Nathan (Tony Revolori) is a sheltered kid setting out for art school in California. His plan is to drive there from his home in Texas, across the American Southwest, taking pictures along the way of strip malls and boarded-up storefronts. He wants to capture the “real America.” He’s a naive kid. A good kid. He has ideas about things, none of which come from actual experience. His car breaks down, and an out-of-work mechanic named Richard (Jason Mantzoukas) helps him out, and also hitches a ride. Richard is headed to Vegas for reasons which remain somewhat obscure. As they bump across Texas, they talk, argue, and get into (and out of) scrapes. Hannah Fidell’s “The Long Dumb Road” (co-written by Fidell and Carson Mell) has the meandering quality of the trip depicted. Nathan has somewhere to go and somewhere to be, but is in no particular rush to arrive. Fidell trusts the dynamic between her two main actors, and allows them a lot of leeway. The conversations have a fresh and improvisational quality. Best of all, she leaves space for the unexpected and the random.

In many ways, “The Long Dumb Road” feels like it hails from the 1970s, a contemporary with lonely mournful travelogues like “The Last Detail” or “Scarecrow,” where men in transition, with loose to nonexistent roots, travel through America, getting sucked into the swirl of life around them even as they try to reach their final destination. The destination recedes the closer they get to it. “The Long Dumb Road” has the same amorphous quality, except without the ’70s malaise. At first, it’s not clear whether or not Richard has some sinister design on Nathan and his purple minivan filled with carefully packed suitcases. Richard’s clothes are filthy, his hair tangled and wild. Richard takes on an older brother role, a wise man, a guy who’s actually lived a little bit. Nathan plays by the rules. His parents may be far back in the rear view mirror, but they still inform who he is and how he acts. “Your generation is 100% pussies,” declares Richard.

The pit stops they take along the way provide the loose structure of “The Long Dumb Road.” They visit Richard’s high school sweetheart (Casey Wilson), whose over-it teenage daughter (Ciara Bravo) gives come-hither glances at Nat, while Richard tries to re-kindle a romance from 15 years before in the next room. It’s absurd. Nothing goes according to plan. A roadhouse drink ends in an altercation with a group of angry guys in trucker hats. A reconnection with one of Richard’s old friends (Ron Livingston) ends in a sucker-punch of surprise and disappointment, leaving Nathan and Richard stranded on a lonely mountain road. They hitch a ride with a park ranger (the great Pamela Reed), who roars with laughter telling about her close encounter with a mama bear and cub. A stopover in a random motel brings them into the orbit of two sisters (Grace Gummer and Taissa Farmiga), also on the road to California, and in the mood to party.

Revolori, who first made a splash in “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” is so alive onscreen he’s great fun to watch, particularly as he listens to Mantzoukas’ ravings, trying to follow the frenzied train of thought. Revolori is reminiscent of Gene Wilder in a lot of ways: he has a highly developed sense of the absurd, but he attempts to maintain his dignity and decorum. It’s the combination that is so funny. Nathan is startled by the insanity of others, and the irrational situations he finds himself in. Mantzoukas is really in a great zone here. His Richard is eccentric and hotheaded, impulsive and intelligent, and you completely believe that someone like Grace Gummer’s party-girl would think she’d hit the jackpot when she met him. The film is built on the chemistry of Revolori and Mantzoukas.

Hannah Fidell’s other films (“Teacher,” “6 Years”) were carefully constructed and, in some cases, over-planned. She’s let go of the reins in “The Long Dumb Road” and all kinds of interesting things are possible as a result. She allows for things to happen, rather than forcing things to happen in order to make specific points. In “The Long Dumb Road,” she soft pedals her cultural critiques, but those critiques are present in every scene, every interaction. It was fun to keep track of how often money is offered in exchange for services rendered. Almost every scene involves someone offering someone else cash, out of pity, a desire to help, a bribe, a payoff. Nathan is the only person who is financially secure, but even then, it’s his parents’ money in his pockets, not his. Richard, unmoored from the grid, mocks Nathan’s privilege but also benefits from Nathan’s generosity. There are a lot of fascinating subtextual things going on. No interaction is truly pure. It’s a given that everything has a price. Maybe that’s the “real America.”