Watching “The Locusts” was like being whirled back in a time warp to the 1950s–to the steamiest and sultriest new work by William Inge or Tennessee Williams about claustrophobic lust in a twisted family. This is the kind of movie that used to star Paul Newman or William Holden, Kim Novak or Natalie Wood or Elizabeth Taylor, with Sal Mineo as the uncertain kid who’s lost in confusion and despair.

Even the big emotional outbursts seem curiously dated. When the alcoholic, resentful, sluttish mother wants to wound her hated and helpless son, for example, what does she do? Staggers out into the rain and castrates his beloved bull, of course. And when it’s truth time, the family secret seems almost inevitable.

The movie is not bad so much as it’s absurd. I never felt I was in the hands of incompetent or untalented filmmakers, and indeed on the basis of “The Locusts,” I anticipate the next film by John Patrick Kelley, its writer-director. He has a talent for rhythm, for mood, for gothic weirdness. This is his first film, and perhaps in trying to fill it with as much atmosphere and passion as possible, he allowed it to become overwrought.

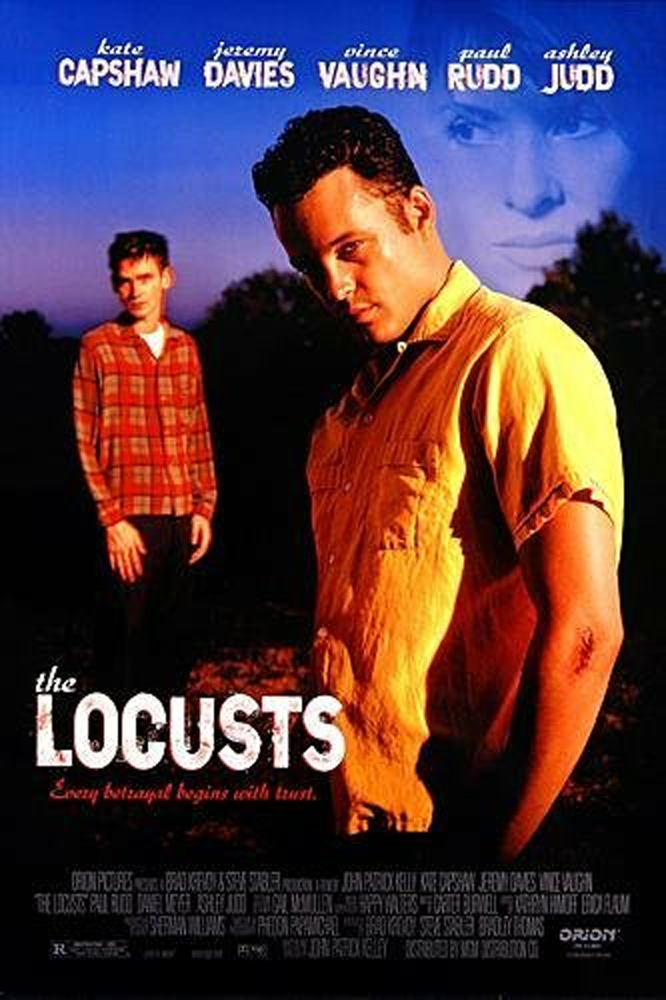

He also has a gift for casting, and the highest praise I can give the performers here is to say they measure up to the 1950s icons I can so easily imagine in the roles. Kate Capshaw is wonderful as Mrs. Potts, the sultry widow who runs a Kansas feed lot, circa 1960, and takes one of her ranch hands into her bed every night. Vince Vaughn, from “Swingers” is far from the fleshpots of Hollywood here. He plays Clay, a drifter with a secret in his past, who turns up in town and is soon parked on lover’s lane with Ashley Judd, as Kitty, the warmhearted local girl who wants to heal his soul. And Jeremy Davies is touching and brave in the role of Flyboy, Mrs. Potts’ son, who has the full gamut of 1950s symptoms: He feels guilty about his father’s suicide, he has spent eight years in an institution getting shock treatments, and now he shuffles around the house as a cowering, mute servant.

All of these characters are created in bold, confident performances of well-written roles. I liked the way Kitty, the Ashley Judd character, cuts to the chase in her dialogue, telling Clay, “So now we’re going to skip the sex and go straight to the brooding?” And Kate Capshaw, her cigarette seen glowing through porch screens on hot summer nights, brings a certain doomed poignancy to the role of a woman whose consolations are whiskey and hired studs.

Because the movie is in some ways so good, it’s a shame it’s so utterly, crashingly implausible. It’s like an anthology of cliches from the height of Hollywood’s love affair with Freud. Of course Clay is running away from a tragedy in his past, and of course Kitty wants to heal him, and of course Mrs. Potts knows a lot more than she’s telling about Flyboy, and of course there will eventually be a showdown between the widow and her new hired hand.

But listen carefully when Clay tells Kitty what happened back in Kansas City. Ask yourself if Clay wasn’t perhaps a mite careless in allowing that incredible chain of events. And ask yourself about the exact chronology of impregnation in the Potts household, and how its menfolk sorted it out. And remind yourself of the old theatrical rule that if a gun comes onstage in the first act, it must be discharged in the third, and ask how that applies to the grisly early scene in which Clay learns how a bull becomes a steer.

There are small, quiet scenes here, however, that are just right. I was moved by Jeremy Davies in a scene where Flyboy pins one of Clay’s playmate fold-outs to a bathroom mirror, lights an unfamiliar cigarette, and engages in conversation with the pinup (he thinks she’ll be interested in hearing about his bull). I admired the real pain Capshaw brought to her final scenes. And there is a wonderful moment when Kitty teaches Flyboy to dance, and then says, “Thank you for the date. It was the best one I ever had.” And Flyboy has a spastic little gesture of joy.

“The Locusts” is not successful. Its material is so overwrought and incredible, so curiously dated, that it undermines the whole enterprise. But it was not made carelessly or cynically, it shows artists trying to do their best, and its makers had ambition. You can sense they wanted to make a great film, and that is the indispensable first step to making one–a step most films do not even attempt.