One is always flummoxed to encounter films about real-life writers that barely bother to reckon with their actual writing. I can’t tell you honestly that I’m much of an expert on Robert Graves. But the version of Graves on display in “The Laureate,” a fictionalized treatment of the unusual living arrangement Graves had between 1924 and 1929, bears only the most superficial resemblance to the author I’ve encountered in the pages of his early autobiography Goodbye to All That, his Claudius novels, his poetic study The White Goddess (have to admit I still haven’t finished this one, which Graves in his intro admits is a “stiff” book) or his poems.

For one thing, it misses Graves’ wit, which could be vicious or teasing. Sometimes rather gentle, sometimes chiding. For the latter, check out this stanza from his poem “The Naked and the Nude”:

The nude are bold, the nude are sly

To hold each treasonable eye.

While draping by a showman’s trick

Their dishabille in rhetoric,

They grin a mock-religious grin

Of scorn at those of naked skin.

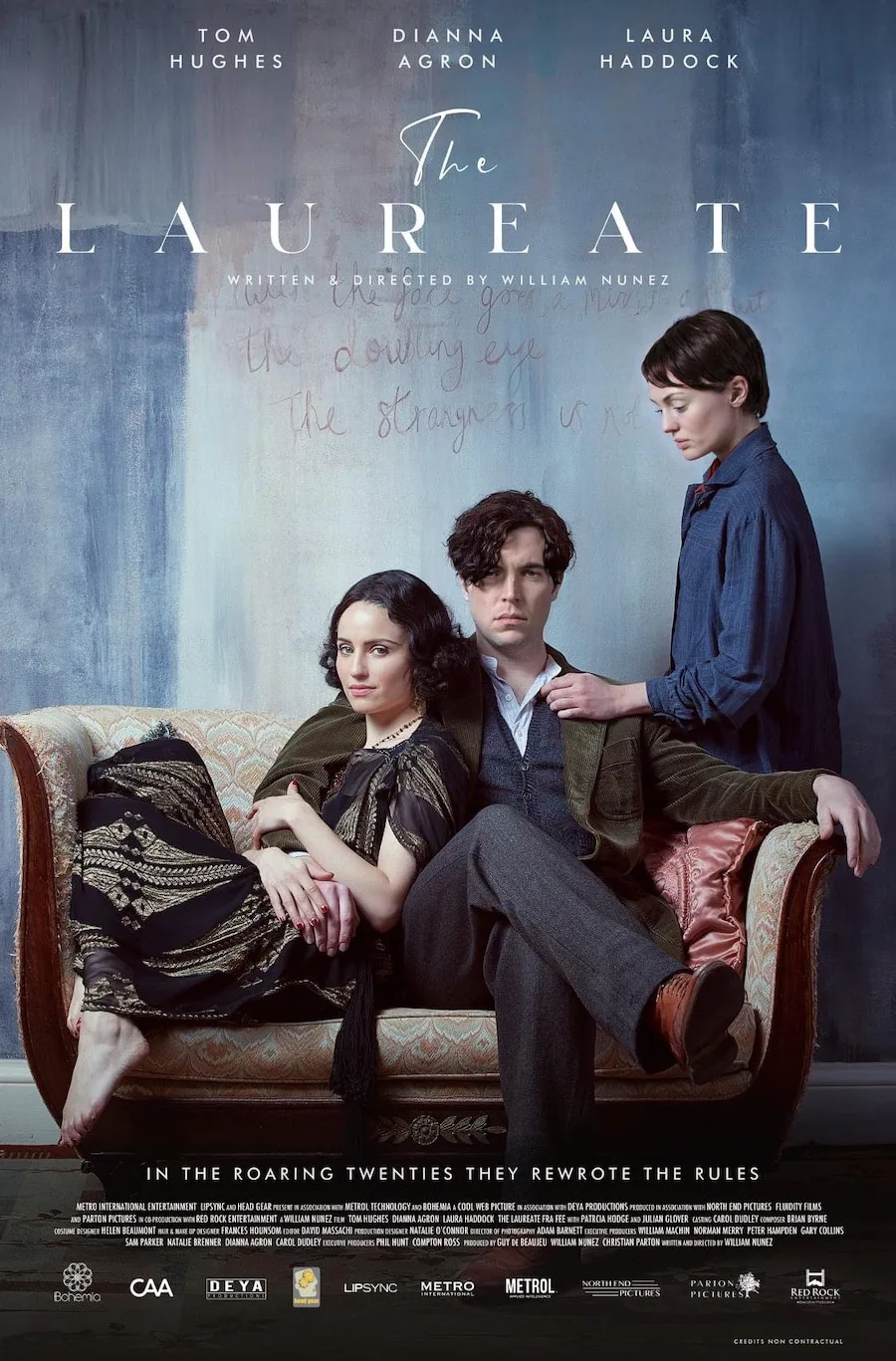

Anyway. In “The Laureate,” written and directed by William Nunez, Graves is still very much a post-war poet, that is a post-World War I poet, and still riven by PTSD. And with good reason; as we hear Tom Hughes as Graves recall in voice-over, he was wounded and left for dead in the Somme, one of the bloodiest battlefields of the war. Haunted by nightmares, jumpy at ringing telephones, the utterly humorless Graves here is seriously unproductive in the house he shares with his wife Nancy (Laura Haddock) and their young daughter Catherine. This house, in Islip, well outside London, is called “World’s End.”

For the sake of narrative coherence, perhaps, the movie hedges with respect to reality. Graves in this period was in fact extremely productive, with several poetry collections and critical studies under his belt; and he and Nancy had not one but four children. Nunez wants us to believe it’s a block that compels Graves to contact a New-York-based poet named Laura Riding, after reading her work.

Riding hops over to England and soon an initially platonic menage-a-trois comes into being. As played by Dianna Agron, Riding is aggressively coquettish. She resembles what smart aleck guys years later came to call (erroneously and condescendingly) a “lipstick feminist.” She gushes to Nancy and Robert that she just adores “Byron, Keats, and Shelley—Mary Shelley, that is!” Nunez thinks, I suppose, that this is an appropriately bold thing for Riding to say. But in fact it’s kind of dippy, making a category error that Riding, whatever her other faults, simply was not prone to as a literary critic.

In the narration that opens the movie, Haddock’s Nancy speaks of inviting a snake into the garden. And boy, does Agron’s Riding slither. In a party scene she flounces about in a negligee like a flapper out of Evelyn Waugh. She seduces Nancy and then Robert (with whom she has a less easy time), then pounces on young poet Geoffrey Phibbs (Fra Fee, here fiercely competing with Hughes for Best Crazy British Poet Hair). She just can’t get enough. Not just of lovin’, but of danger. At one point she goads the Graves’ daughter into nearly walking out of a window. All the while looking very pleased with herself.

Nunez is hardly the first male to take a misogynist view of Laura Riding. She could, as her life vividly demonstrates, be extremely melodramatic, to say the least. And if she’s not read as widely today as Graves is, there are reasons that aren’t just due to her later writing being highly theoretical. But it’s a little surprising, in this day and age, to see such a conception get such a thorough workout in a not-cheap period movie. And for Agron to seemingly buy into that conception so whole heartedly. (Although given how idiosyncratic the thought processes of individual performers can be, who knows what she thought she was doing.) One thing is certain: for all the strain the movie exerts, it never comes close to touching the hem of the writers it purports to depict. And it leaves the mystical and erotic dimensions of their lives and works far outside of its belabored vision.