Watching “The Last Station,” I was reminded of the publisher Bennett Cerf’s story about how he went to Europe to secure the rights to James Joyce’s Ulysses.

“Nora, you have a brilliant husband,” he told Joyce’s wife. “You don’t have to live with the bloody fool,” she responded.

If Joyce was a drunk and a roisterer, how different was the Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, who was a vegetarian and pacifist, and recommended (although did not practice) celibacy? “The Last Station” focuses also on his wife, Sofya, who after bearing his 13 children thought him a late arrival to celibacy and accused him of confusing himself with Christ. Yet it’s because of the writing of Joyce and Tolstoy that we know about their wives at all. Well, the same is true of George Eliot’s husband.

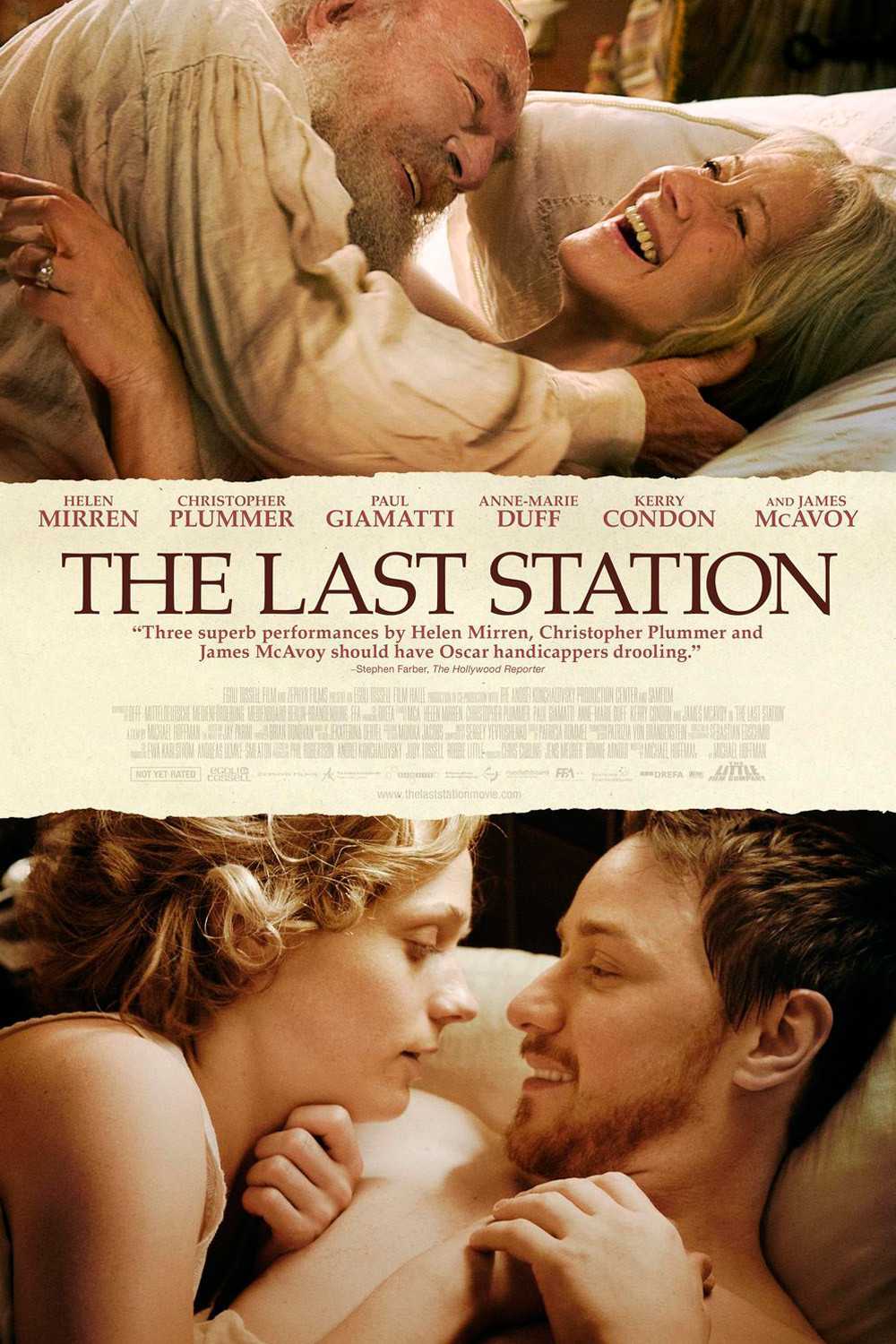

“The Last Station” focuses on the last year of Count Tolstoy (Christopher Plummer), a full-bearded Shakespearian figure presiding over a household of intrigues. The chief schemer is Chertkov (Paul Giamatti), his intense follower, who idealistically believes Tolstoy should leave his literary fortune to the Russian people. It’s just the sort of idea that Tolstoy might seize upon in his utopian zeal. Sofya (Helen Mirren), on behalf of herself and her children, is livid.

Chertkov, the quasi-leader of Tolstoy’s quasi-cult, hires a young man named Valentin (James McAvoy) to become the count’s private secretary. In this capacity, he is to act as a double agent, observing moments between Leo and Sofya when Chertkov would not be welcome.

It might be hard for us to understand how seriously Tolstoy was taken at the time. To call him comparable in stature to Gandhi would not be an exaggeration, and indeed Gandhi adopted many of his ideas. Tolstoy in his 82nd year remained active and robust, but everyone knew his end might be approaching, and the Russian equivalent of paparazzi and gossips lurked in the neighborhood. Imagine Perez Hilton staking out J.D. Salinger.

Tolstoy was thought a great man and still is, but in a way his greatness distracts from how good he was as a writer. When I was young, the expression “reading War and Peace” was used as a synonym for idly wasting an immense chunk of time. Foolishly believing this, I read Dostoyevsky and Chekhov but not Tolstoy, and it was only when I came late to Anna Karenina that I realized he wrote page-turners. In Time magazine’s compilation of 125 lists of the 10 greatest novels of all time, War and Peace and Anna Karenina placed first and third. (You didn’t ask, but Madame Bovary was second; Lolita, fourth, and Huckleberry Finn, fifth.)

“The Last Station” has the look of a Merchant-Ivory film, with the pastoral setting, the dashing costumery, the meals taken on lawns. But did Merchant and Ivory ever deal with such a demonstrative family? If the British are known for suppressing their emotions, the Russians seem to bellow their whims. If a British woman in Merchant-Ivory land desires sex, she bestows a significant glance in the candlelight. Sofya clucks like a chicken to arouse old Leo’s rooster.

The dramatic movement in the film takes place mostly within Valentin, who joins the household already an acolyte of Tolstoy. Young and handsome, he says he is celibate. Sofya has him pegged as gay, but Masha (Kerry Condon), a nubile Tolstoyian, pegs him otherwise. Valentin also takes note that Tolstoy, like many charismatic leaders, exempts himself from his own teachings. The 13 children provide a hint, and his private secretary cannot have avoided observing that although the count and countess fight over his will, a truce is observed at bedtime, and the enemies meet between the lines.

As the formidable patriarch, Christopher Plummer avoids any temptation (if he felt one) to play Tolstoy as a Great Man. He does what is more amusing; he plays him as a Man Who Knows He Is Considered Great. Helen Mirren plays a wife who knows his flaws, but has loved him since the day they met. To be fair, no man who wrote that fiction could be other than wise and warm about human nature.

Some women are simply sexy forever. Helen Mirren is a woman like that. She’s 64. As she enters her 70s, we’ll begin to develop a fondness for sexy septuagenarians.

Mirren and Plummer make Leo and Sofya Tolstoy more vital than you might expect in a historical picture. Giamatti has a specialty in seeming to be up to something, and McAvoy and Condon take on a glow from feeling noble while sinning. In real life, I learn, Tolstoy provided Sofya with more unpleasant sunset years, but could we stand to see Helen Mirren treated like that?