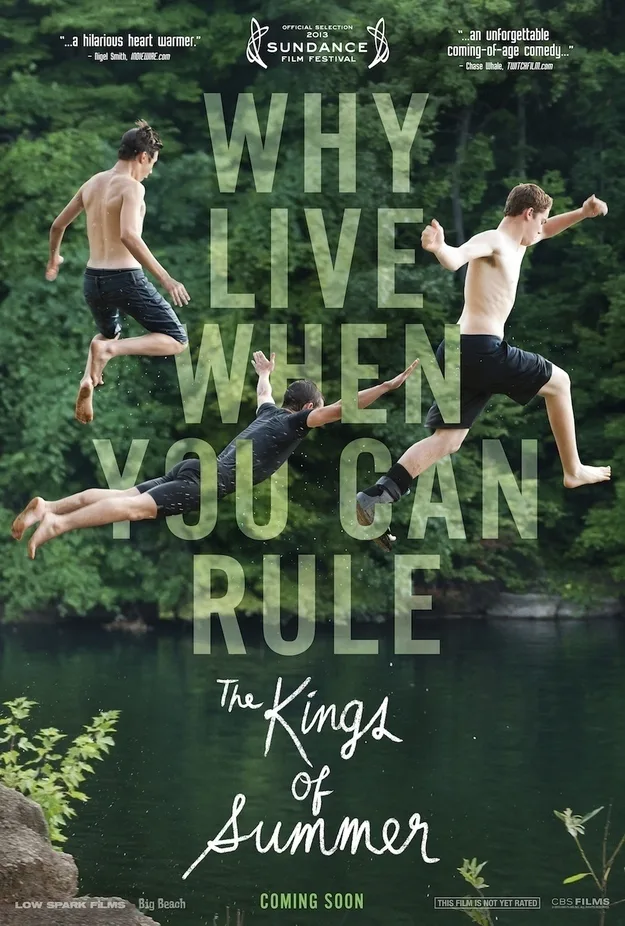

High school student Joe (Nick Robinson) lives with his father (Nick Offerman), a stern man sitting on a volcano of anger. Joe’s mother has died. He has an older sister (played by “Mad Men”‘s Alison Brie), but she is engaged and out of the house. The tension between father and son is oppressive, and the rules feel arbitrary and unfair to Joe. During one night when the family gathers to play Monopoly, like they used to do when Mom was alive, the tension explodes. Joe didn’t want to play anyway, he wanted to go to a party with his friends. After a fight with his dad, Joe ends up calling the police, claiming physical abuse. It’s a radical move, dark and evocative of a deep psychological schism. There’s a furious and smart movie inside “The Kings of Summer,” a first feature by director Jordan Vogt-Roberts, a film about three teenage boys who take to the woods to build a house from scratch and live outside not only parental supervision but community norms and expectations. Unfortunately, despite some beautiful sequences and solid acting, the script by first-timer Chris Galletta pulls its punches, over-explains the emotional meaning of its moments, and tries to lighten the mood in sometimes awkward sit-com-style ways, betraying the movie’s more honest spirit. “The Kings of Summer” flirts with profundity, seeming to yearn for it and fear the honest expression of it at the same time. There is much here to admire, but the overall impression is of a film that does not have the courage of its convictions.

Joe and his buddy Patrick (played by the open-faced and extremely talented Gabriel Basso) have been friends since childhood. Joe has issues with his father, and Patrick is heckled and cooed over by his intrusive well-meaning parents (played, hilariously, by Megan Mullally and Marc Evan Jackson). Nothing seems bad enough here to warrant anyone running away, but “The Kings of Summer,” to its credit, is going after a deeper more existential truth, common to most coming-of-age movies, the fact that teenagers are not only looking for freedom, but meaning in their lives. They want to be free to feel deeply, to connect to themselves in respect to their environments, and to choose a life that suits them.

One night, after a party, Joe and another kid, a bizarre human being named Biaggio (Moises Arias, who is phenomenal in the role) get lost coming home through the woods. They come upon an open glade, dark and mysterious in the moonlight, so beautiful that the two boys stop dead in their tracks. Joe gets the idea to remove himself from his father’s home, and build a house in the woods with Patrick. Biaggio, since he was there that first night, is along for the ride. Patrick bones up on survivalist books from the library, treating the project seriously, liking the image of freedom and manliness that Joe paints for him. They draw floor plans, they pilfer materials from construction sites, they spend their days out in the woods building their house. And then, one night, all three sneak away from home and move in.

The community, of course, thinks they have been kidnapped and two cops (Mary Lynn Rajskub and Thomas Middleditch, both fantastic) are assigned to investigate. The parents back home wonder what they did, and Joe’s dad, in one awful line, confesses to Patrick’s dad, “I think I’ve broken my son.”

Meanwhile, out in the woods, the three boys revel in an unfettered life, trying to catch fish and other critters, so that they will be entirely self-sufficient. Joe makes many speeches about masculinity, the script constantly reminding us of the themes underlying the adventure.

There are some good scenes where we see that a geographical change does not necessarily solve your problems. Patrick tries to tell the other boys not to litter, because it will attract animals, and Joe blows off the advice, annoyed at being told what to do. Joe has a crush on a girl, Kelly (Erin Moriarty), and despite their rule of telling no one about their Swiss Family Robinson/Moonrise Kingdom situation, Joe caves and invites her to visit. She brings a couple of friends. Over a night around the campfire, it becomes clear that Kelly is falling for Patrick, not Joe. Joe reacts with jealousy and rage, exploding at Patrick, referring to Kelly as a “bitch”, and behaving like the worst kind of emotional bully. As a matter of fact, the contempt he shows for both of them is reminiscent of his father’s cold judgmental attitude. If this is what “being masculine” means to Joe, it is, perhaps understandable, due to his father’s poor example, but the film does not delve deeper into it. It is a giant missed opportunity.

Patrick, on the other hand, seems to have a comfort with himself that is natural and easy, igniting Joe’s envy. There is a beautiful random shot, unconnected to any other scene, of Patrick sitting in the woods by himself playing a mournful tune on a violin. It’s gorgeously shot, and one of the few scenes where everyone is not talking about what everything means. While sitting around the campfire with the girls, we see Patrick going out of his way to make Kelly laugh. Again, the script trembles on the edge of profundity here, making acute observations about different aspects of masculinity, one of them being the ability to include women in that male circle, and to do so without hostility.

Lightening the mood with humor is important to such potentially painful material, and there are a couple of legitimately hilarious scenes, mostly involving the self-serious behavior of the two cops, Patrick’s parents’ comedy routine with one another, and Biaggio’s deadpan line delivery. But some of the schtick feels either forced or unfocused, one exchange about cystic fibrosis in particular. Lines from Biaggio like “I don’t see myself as having a gender” or “I can read. I just can’t cry” are not explored in a meaningful way. His words are treated as one-liners, tossed off to make an audience laugh, and never visited again, but they act as glimpses of the more honest and interesting movie that could have been. And Joe, who behaves poorly out there in the woods, never seems to come to a realization that he needs to take responsibility for his behavior. Being a man, being an adult, doesn’t just mean doing whatever the hell you want to do. The script shies away from its own implications.

Vogt-Roberts’ direction is often evocative and beautiful, bordering on the surreal at times, his filming of their first glimpse of the glade by moonlight a perfect example. The montage of the boys building the shack in the woods is energetic and emotional. He has a good eye for the interesting, for the unusual image. The over-written script is to blame here. It wants to make sure we get the symbols and metaphors going on, but it also doesn’t want to be caught taking itself too seriously. This is an error. Peter Bogdanovich once asked John Wayne about his famously bold gestures onscreen, and Wayne replied, “I think that’s the first lesson you learn in a high school play — that if you’re going to make a gesture, make it.” “The Kings of Summer” should take that advice. You have a gesture you want to make, so make it.