When poker players want to make the game a little more interesting, they either raise the stakes or declare a wild card. Woody Harrelson has the same effect on a movie. He has a reckless, risky air; he walks into a scene and you can’t be sure what he’ll do. He plays characters who are a challenge to their friends, let alone their enemies.

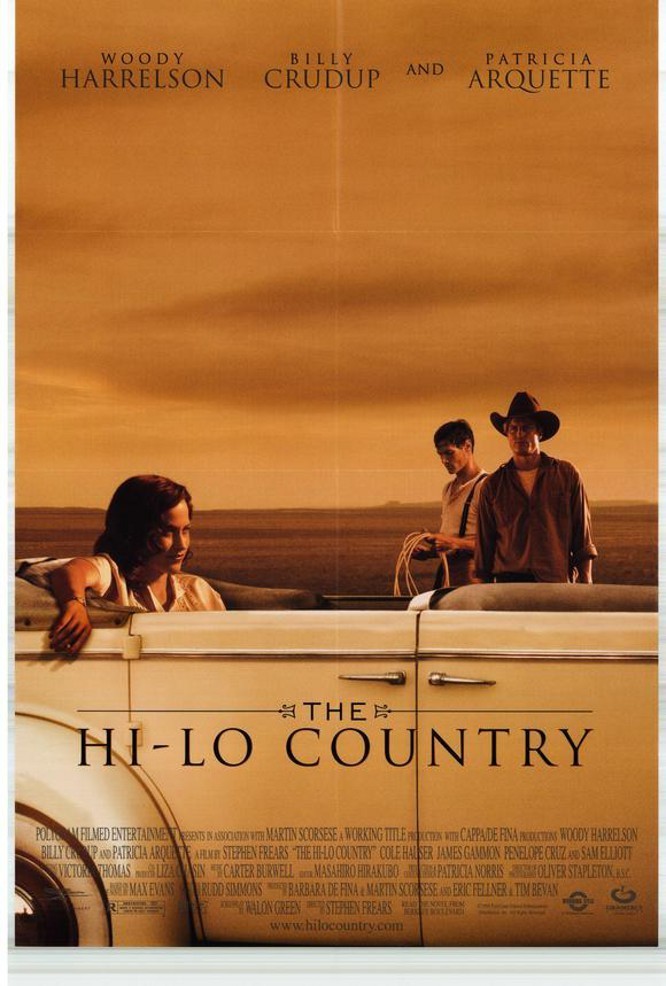

In Stephen Frears‘ “The Hi-Lo Country,” Harrelson has an energy the rest of the film lacks. He plays a variation on that old theme, the Last of the Cowboys, but does it with a modern irony. Watching his character tame unruly horses and strut into bars, I was reminded of a line from a completely different kind of movie, “A New Leaf,” where the aging playboy is told, “You are carrying on in your own lifetime a way of life that was dead before you were born.” Harrelson plays Big Boy Matson, a man’s man in the arid Hi-Lo country of New Mexico. He’s seen through the eyes of the film’s narrator and nominal hero, Pete Calder (Billy Crudup), who returns to the area after serving in World War II and plans to raise cattle. He’s advised against it by the rich local rancher Jim Ed Love (Sam Elliott), who says the days of the independent herds are over and gone. “People still drive cattle to rail heads,” Pete tells him. “Only in the movies,” Jim Ed says.

The movie evokes the open space of New Mexico with a bright, dusty grandeur; Oliver Stapleton’s camera places the characters in a wide-screen landscape of weathered buildings, lonesome windmills and distant mountains. There do not seem to be enough people around; the inhabitants of the small town live in one another’s pockets, and there are no secrets.

One secret that would be hard to keep is the allure of Mona (Patricia Arquette), a local man’s wife who dances on Saturday nights at the tavern as if she might go home with the next man who takes her out on the floor. Mona likes Pete. Indeed, the first time she sees him after the war, at the tavern, she all but propositions him: “Am I keepin’ you from something? Or someone? You look good, Pete. Real good.” Pete dances with her, and confides in a voice-over, “She was right. I was lookin’ for someone. She came up against me like silver foil, all fragrance and warm pressure.” That’s not the sort of line a New Mexico cowboy is likely to use in 1946, but there’s a kind of distance between the hard-boiled life of the Hi-Lo country and the poetry of the film, which wants the characters steeped in nostalgia and standing for a vanishing way of life. The screenplay is by Walon Green, who also wrote “The Wild Bunch,” which was more hard-boiled about nostalgia.

Mona’s problem is, as good as Pete looks to her, Big Boy looks better. That’s who she really loves, and who really loves her. But Big Boy is untamed, just like Old Sorrel, the unruly horse he bought from Pete.

And Big Boy is incautious in his remarks. Even though Mona is married to a man with friends who have guns, Big Boy makes reckless announcements for the whole bar to hear, like, “A good woman’s like a good horse–she’s got bottom. Mona’s gonna make me a partner to go along with Old Sorrel.” The romantic lines grow even more tangled because there is, as there always is in a Western, a Good Woman who steadfastly stands up for the hero even while he hangs out with the boys and the bad girls. This is Josepha (Penelope Cruz), a Mexican-American. Pete was seeing Josepha before the war. She loves Pete, and Pete says he loves her (he lies), and she knows about Mona: “She’s a cheap ex-prostitute and a phony.” Mona may be, but she’s sincere in her love for Big Boy, and in one way or another that drives most of the plot. The underlying psychology of the film is in the tradition of those Freudian Westerns of the 1950s, in which a man was a man but a gun was sometimes not simply a gun. There’s a buried attraction between Big Boy and Pete, who not only sleep with the same woman (and know they do) but engage in roughhouse and camaraderie in a way that suggests that no woman is ever going to be as important to them as a good buddy (or a horse). Jim Ed Love of course represents patriarchal authority: He stands for wisdom, experience and money, and for telling boys to stop that fooling around and grow up.

Stephen Frears is an Irish director who therefore grew up steeped in the lore of the American West. (Country music is more popular in Irish pubs than in some states of the union.) He’s seen a lot of revisionist modern Westerns (especially “Giant”), and he gets the right look and feel for his film. But I think he brings a little too much taste and restraint to it. If he had turned up the heat under the other characters, they could have matched Big Boy’s energy, and the movie could have involved us in the way a good Western can.

Instead, “The Hi-Lo Country” is reserved and even elegiac. It’s about itself, rather than about its story. The voice-over narration insists on that: It stands outside and above the story, and elevates it with self-conscious prose. By the end, we could be looking at Greek tragedy. Maybe that’s the idea. But Harrelson suggests another way the movie could have gone. With his heedless energy and his sense of complete relaxation before the camera (he glides through scenes as easily as a Cary Grant), he shows how the movie might have been better off staying at ground level and forgetting about the mythological cloud’s-eye view.

Note: Two small scenes deserve special mention. One involves the legendary Mexican actress Katy Jurado, as a fortune-teller. When the boys visit her, she’s asked if “all of us who are here will be alive and prosperous next year.” They get their money’s worth: “No.” The other show-stopper is a country singer named Don Walser, whose high, sweet voice provides a moment when the movie forgets everything and just listens to him.