“The Heiresses,” a Paraguayan drama written and directed by Marcelo Martinessi, could be called a quiet movie. There aren’t too many earth-shaking moments. The plot is minimal. But underneath the film’s quiet is a heaving ocean of longing, restlessness, melancholy. At the film’s start, we enter a world where time has essentially stopped, for decades. The characters’ routines do not bring them happiness, not that we can tell, but the routines are all that they know. Over the course of the film, those routines are shattered and suddenly time starts rushing forward again, bringing with it the unexpected, the painful, the joyful. Emotions never before experienced come surging to the surface. How Martinessi pulls this off—in what is his first feature—is nothing less than extraordinary.

Chela (Ana Brun) and Chiquita (Margarita Irun) have been together for 30 years, a lesbian couple of the elite class, living in a large home in Paraguay’s capital Asunción. Their relationship is one of opposites: Chela, a painter, is introverted and subdued, while Chiquita is extroverted and passionate. Their home is filled with family heirlooms, all of which they are auctioning off to pay Chiquita’s massive debts. When Chiquita is given a short prison sentence for fraud, Chela is left alone in the home for the first time. Before Chiquita goes to prison, she hires a maid (Nilda Gonzalez), training her in how Chela likes her breakfast tray arranged. Chela and Chiquita live in a world where you no longer have any furniture in your house, and one of you is off to jail because of unpaid debts, but you still have a maid. “The Heiresses” is filled with details like this, the unspoken assumptions of class and privilege, and what happens when those boundaries start breaking down.

Chiquita flourishes in prison, picking up on the rules and making friends. She’s a hot shot. Chiquita is adaptable to circumstances, whereas Chela—totally thrown if the coffee cup on her breakfast tray is placed with the handle facing the wrong way—is rigid, unable to adjust. Her footsteps echo through her increasingly empty house. Almost by accident, and despite the fact that she doesn’t have a driver’s license, she finds herself running an ad hoc taxi service for her elderly next-door neighbor Pituca (María Martins), using her father’s Mercedes (which she so far has refused to sell). Angy (Ana Ivanova), the daughter of one of Pituca’s friends, hires Chela to drive her mother to doctor’s appointments. Suddenly Chela is so busy with her new taxi life, and so drawn to the sensuous Angy she’s like a high school girl with a crush, she misses visiting day at the prison.

The shifting stratification of class and rank in “The Heiresses” is one of its many fascinations, as well as central to how it operates. Chela and Chiquita are of the elite, but their home is falling into ruin. Chela drives a Mercedes but it’s so old sometimes it won’t start. In the hierarchy of service, being a maid is better than driving a taxi, and Chela, surrounded by her family’s crystal and china, is now on the bottom of the heap. Angy, a much younger woman, operates in a world of sexual possibility, and in that world, none of these class distinctions matter. Martinessi is sensitive to power dynamics and the various layers of privilege in operation in almost every exchange.

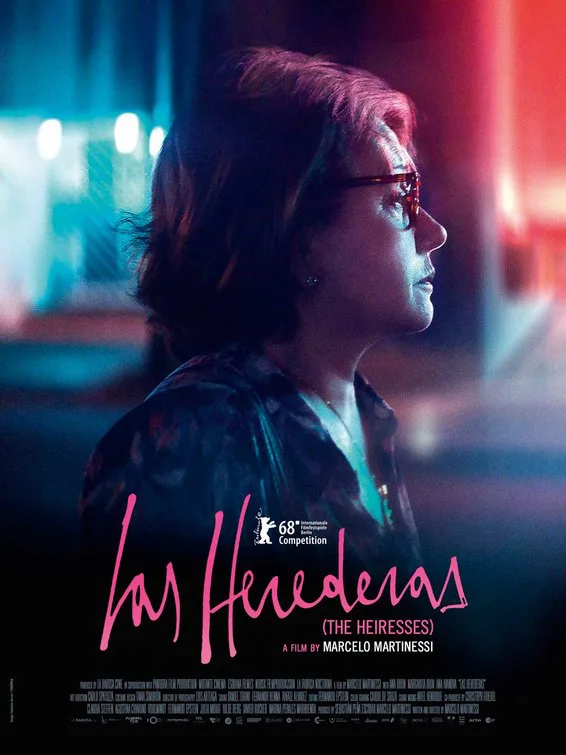

Brun won Best Actress at Berlin last year for her performance as Chela. It is—astonishingly—her first film credit (although she has a successful stage career in Paraguay). Brun’s performance as Chela works by stealth. In the opening sequences, her devastation at their financial ruin runs so deep it’s always present on her face, a simmering mix of panic, despair, and humiliation. Misery exhales off of her. It’s hard to tell exactly when things start to shift, and part of the film’s tension comes from watching Brun’s slow transformation. While this may sound like another entry in the “middle-aged lady gets her groove back” genre, “The Heiresses” is up to something a little bit different, a little bit darker, and much of that is due to Brun’s performance. Chela’s emotions, her hopes, her attraction to Angy, her loneliness … all of these things threaten to overwhelm her (and us). Brun’s vulnerability is profound. Chela is so weighted down at the start of the film that the lightening of her mood is wonderful to see but it’s also alarming. Hope brings with it the possibility of heartbreak, and Brun draws you totally into that experience, with little to no explanatory dialogue. What a remarkable performance.

Cinematographer Luis Armando Arteaga helps create the Chekhovian mood of “The Heiresses,” filming in widescreen, turning Chela and Chiquita’s decaying house into a prison of shadows, with no real way out. With every scene, more furniture vanishes from those dark rooms. The stained wallpaper shows the outlines of picture frames, taken down after decades. It is a place trapped in time, a relic, surrounded by the rise of a confusing present and future, where class hierarchies and certainties no longer carry weight.

It is in the unspoken where “The Heiresses” is its most powerful. The truth is somewhere between the lines. Within this story of a woman joining the river of time again, you can glimpse an entire culture’s struggle to move out of the past and lurch into the future, into the unknown.