How can she finish school, get basketball taken care of and be a mommy? –Talk-show caller

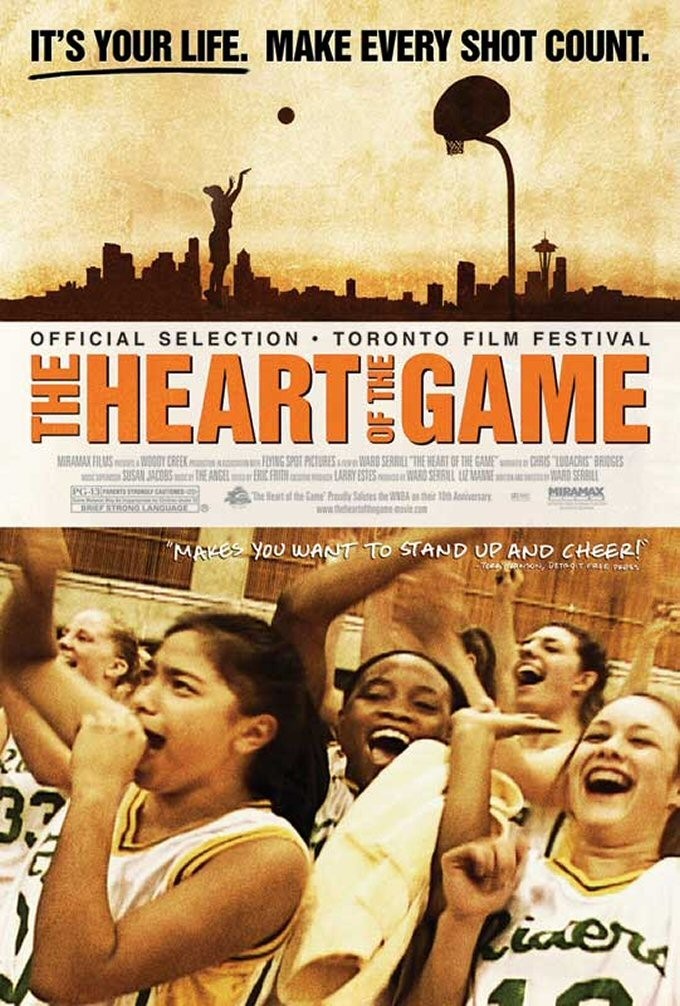

How can she not? “The Heart of the Game” tells the story of Darnellia Russell, a young woman who leads her Seattle high school basketball team to a state championship, graduates with honors, and is a mommy — despite the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association, which sues to prevent her from playing during her senior year. It is also the story of Bill Resler, a professor of tax law who looks like Santa Claus and coaches like a saint. “Have fun!” he says after every time out.

“The Heart of the Game,” like “Hoop Dreams,” is a basketball documentary that began with no idea of where its story would lead. It begins in the classroom of Resler, a professor at the University of Washington, who hears that Roosevelt High School is looking for a new women’s basketball coach, and applies for the job. A man in his 50s, he has three grown daughters and always followed their teams; now he gets to coach, although he keeps the day job and we get the impression that as coach his salary is little or nothing.

Resler’s coaching philosophy is simple: “A full-court press the whole game. No offensive strategy, just run like hell.” He runs his first team up and down the court until they drop, but he turns Roosevelt’s Roughriders around and they start winning. “You can’t defend against them,” an opponent complains, “because even they don’t know what they’re going to do next.”

Resler recruits Darnellia Russell, a middle school star across town, for Roosevelt. It’s a middle-class school with a majority of white students; her closest high school, Garfield, is mostly black. Darnellia’s mother April thinks her child will “do better” at Roosevelt.

At first, she doesn’t. She skips practices and her grades are bad; the film’s narrator (Ludacris) tells us she is “intimidated by how to be around so many white people.” Resler works with her, encourages her studies, tells her he’ll throw her off the team if she isn’t at practice on time. “What I know,” he says, “is that Darnellia is brilliant. The one issue she has to conquer is, believing in how smart she is.”

Resler names each of his Roughrider teams. We live through the seasons of the Pack of Wolves, the Tropical Storm, the Pride of Lions. He takes them to state finals Darnellia’s sophomore and junior year; then she gets pregnant by the boy she’s been dating since ninth grade. She drops out to have the baby. Her mother and grandmother support her, and she applies to return for a senior year. That’s when the WIAA steps in and sues to prevent her from playing again, threatening the Roughriders with forfeiting every game. The team votes to play anyway.

It’s here that the film’s politics become fascinating. The interscholastic association’s bylaws allow exceptions in the cases of “hardships,” but the WIAA says pregnancy is not a hardship: “She made her own choice.” Callers to local talk shows argue against her; I quote one at the top of this review. But Seattle lawyer Kenyon E. Luce volunteers to represent Darnellia in court, and wins. The WIAA appeals. His argument is that since male players are not punished when they’re responsible for a pregnancy, it is discriminatory to penalize a pregnant woman.

Consider the WIAA argument: “She made her own choice.” Yes, she did. She chose to have her baby. If she had chosen to have an abortion, she could have played next season, no questions asked. It is here that the values of the talk show callers get confused. They apparently believe Darnellia should have the baby, but be penalized for having it. Yes, abstinence is also a choice, but tell that to a weeping teenage girl locked in the bathroom with a drugstore pregnancy kit.

Darnellia’s final season combines the legal court battle with a cross-town rivalry; its traditional arch-enemy Garfield is now coached by the women’s basketball legend Joyce Walker. Garfield has a tall team; Darnellia is 5-7, and Resler lists all of his starters as “guards.” Director Ward Serrill, who has been following Resler since the day he took his job, is allowed into practice sessions and halftime locker rooms, but not into the “inner circle,” a meeting of the team members themselves, with no one else present — including Resler.

“Look in their eyes!” Resler screams from the sidelines, a reminder that lions are the only animal that will return man’s gaze. Is he obsessed with winning? There are more important things. Since the whole team voted to risk forfeiting their season, he decides that every single team member will play in the state championship game, no matter what the score is.

Sports movies have a purity of form. They always end with the big game, in triumph or heartbreak. So does “The Heart of the Game,” although the lawsuit still hangs over the team after the final free throw. By then we have come to have real respect for Russell’s determination: Her grades improve so much she’s on the honor roll, her baby is getting lots of mothering, fathering, grandmothering and great-grandmothering, and she is voted player of the year.

Only later do questions occur. Resler casually mentions getting married in Alaska. It is apparently a second marriage, but we never meet his wife and he never talks about her. When your husband is a university professor and takes on a second job that is arguably full-time, does that cause problems? And although we see Darnellia’s boyfriend several times, we never hear from him, nor does her mother talk directly about Darnellia’s pregnancy. There are other stories stirring below the surface.

But perhaps by focusing on basketball itself, on the game and the legal and moral issue of Darnellia’s pregnancy, the movie has enough to contend with. “The Heart of the Game” has the potential, like “Hoop Dreams,” to win a large audience. And Darnellia Russell, like William Gates and Arthur Agee in that film, has the potential to use basketball as a way to graduate from college and have a better life.