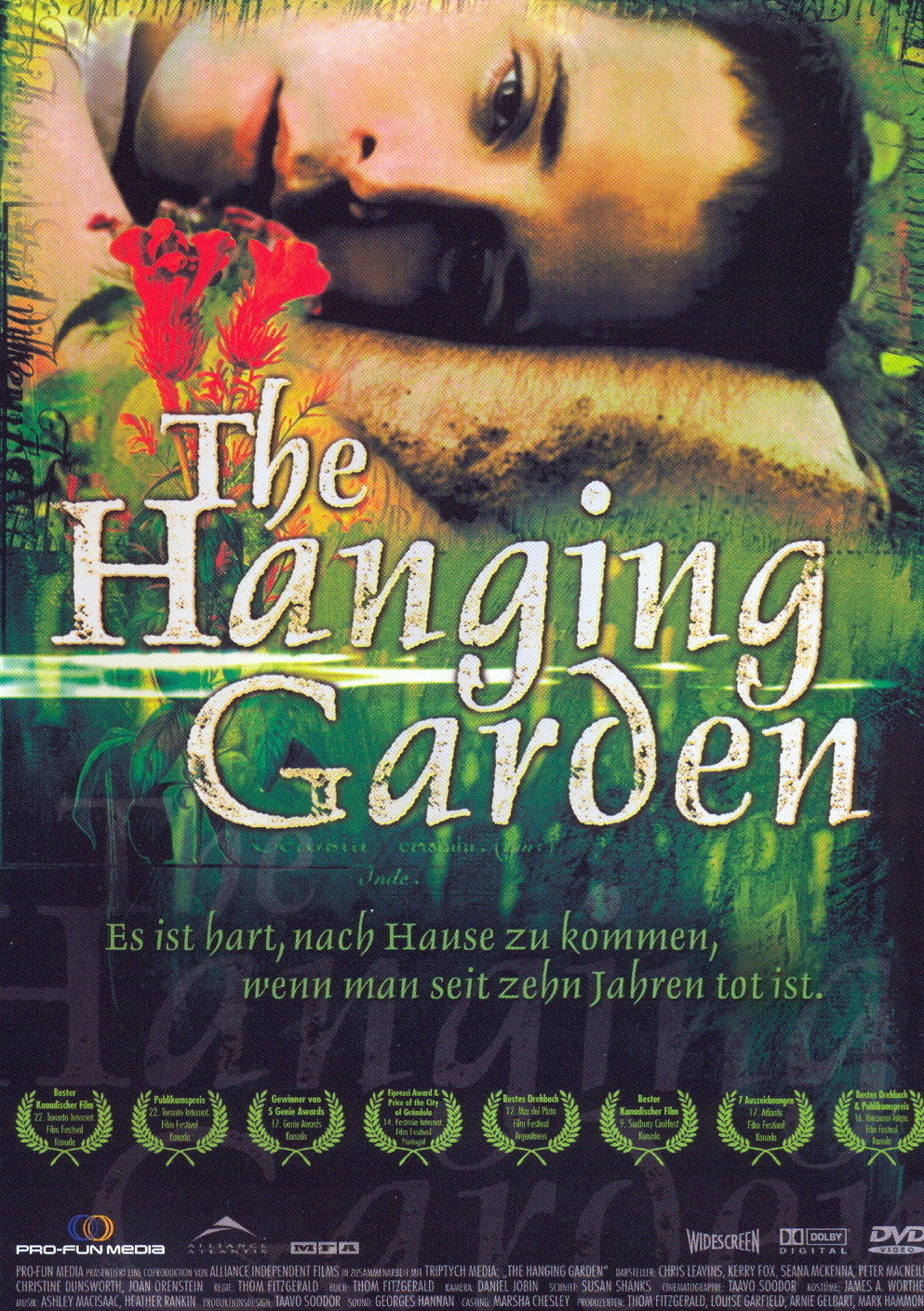

There is a character named William who appears in “The Hanging Garden” at three different ages: as an 8-year-old who is terrified of his father, as a fat 15-year-old and as a 25-year-old, now thin, who has returned for his sister’s wedding. The peculiar thing is that the characters sometimes appear on the screen at the same time, and the dead body of the 15-year-old hangs from a tree during many of the scenes.

Well, why not? It may be magic realism, but isn’t it also the simple truth? Don’t the ghosts of our former selves attend family events right along with our current manifestations? Don’t parents still sometimes relate to us as if we were children, don’t siblings still carry old resentments, aren’t old friends still stuck on who we used to be? And don’t we sometimes resurrect old personas and dust them off for a return engagement? Aren’t all of those selves stored away inside somewhere? The movie opens on a wedding day. Rosemary (Kerry Fox, from “An Angel at My Table”), who has already started drinking, struggles with her wedding dress and vows she won’t show herself until her brother arrives. Her brother Sweet William (Chris Leavins) does eventually arrive, late, and is about 150 pounds too light to fit into the tux his mother has rented for him. He was fat when he left home. Now he is thin, and gay. We learn that his first homosexual experience was with Fletcher (Joe S. Keller), the very person Rosemary is planning to marry.

The family also includes Whiskey Mac (Peter MacNeill), the alcoholic patriarch, and Iris (Seana McKenna), the mother, who seems like a rock of stability. It’s no accident that all the family members are named for flowers; Whiskey Mac poured all of his love and care into his garden, while brutalizing his family. His treatment of his overweight, gay son led the boy to hang himself in one version of reality, and to run away in another, so that when the 25-year-old returns home the body of the 15-year-old is still hanging in the garden.

But I am not capturing the tone of the movie, which is not as macabre and gloomy as this makes it sound, but filled with eccentricity. The family members, who live in Canada’s Maritime provinces, have survived by becoming defiantly individual. This is going to be one of those weddings where the guests look on in amazement.

Writer-director Thom Fitzgerald moves easily through time, and we meet the teenage version of Sweet William (Troy Veinotte) and Rosemary (Sarah Polley, from “The Sweet Hereafter”) as they form a bond against their father. Fitzgerald never pauses to explain his time-shifts and overlaps, and doesn’t need to. Somehow we understand why a 300-pound body could be left hanging from a tree for 10 years. It isn’t really there, although in another sense of course it is.

Like many movies about dysfunctional families, “The Hanging Garden” involves more dysfunction than is perhaps necessary. There is the grandmother, who is senile but still has good enough timing to shout “I do!” out the window at the crucial moment in the marriage. And the tomboy little sister, Violet, who bitterly resents having to be the flower girl. And for all the secrets I have suggested, there are others that will surprise you even at the end–including a great big one that I doubt really proves anything.

The heart of the movie is its insight into the way families are haunted by their own history. How the memory of early unhappiness colors later relationships, and how Sweet William’s persecution by his father hangs in the air as visibly as the corpse in the garden.

The movie is Canadian, and joins a list of other recent Canadian films about dread secrets, including “Exotica,” “The Sweet Hereafter” and “Kissed.” Although there’s a tendency to lump Canadian and American films together into the same cultural pool, the personal, independent films from Canada have a distinctive flavor. If Americans are in your face, Canadians are more reticent. If a lot of American movies are about wackos who turn out to share conventional values at the core, Canadian characters tend to be normal and pleasant on the surface, and keep their darker thoughts to themselves. I don’t know which I prefer, but I know the Canadians usually supply more surprises.