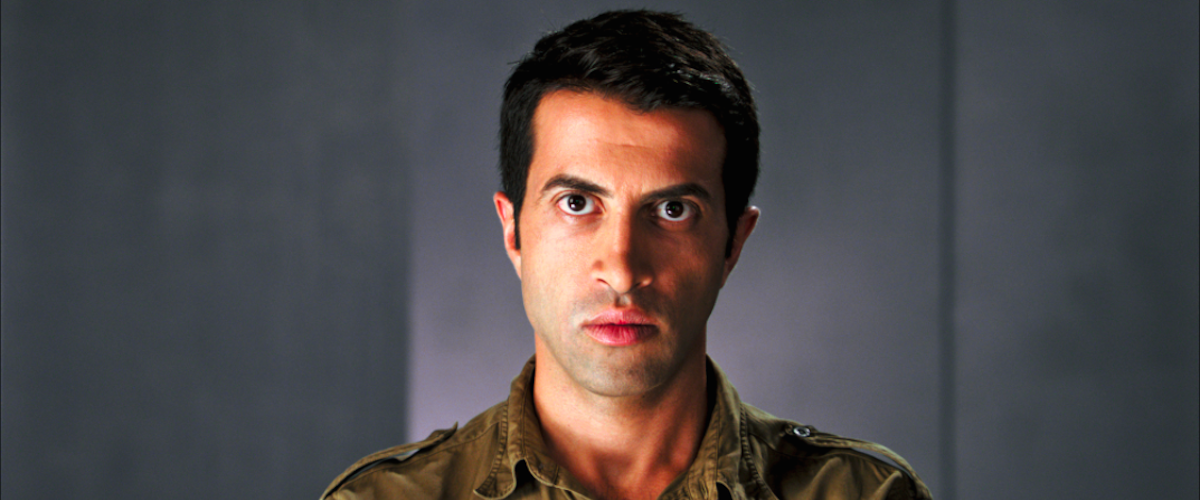

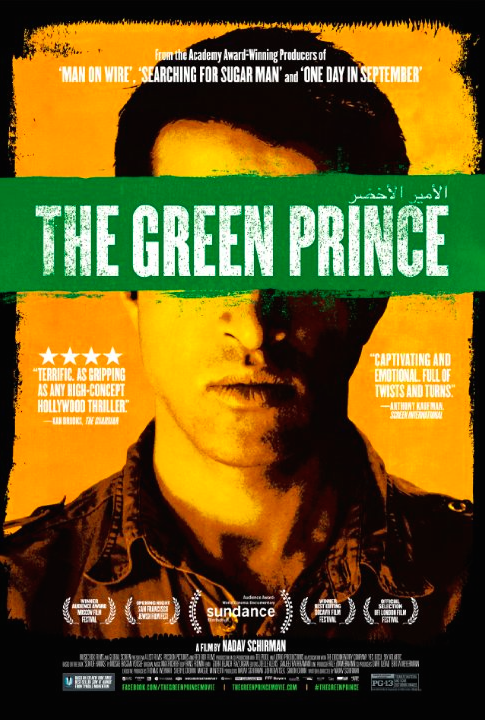

Nadav Schirman’s documentary “The Green Prince” addresses the Israel-Palestine conflict through the intimate, personal story of Mosab Hassan Yousef. Yousef titled his memoir “Son of Hamas,” as he was the eldest son of one of that organization’s most prominent voices. But to Shin Bet, the Israeli security agency with which he collaborated for 10 years, Yousef was known by the colorful royal name that gives this film its title.

Rather than shape his film into hero worship or indictment, Schirman simply lets his subject tell his story to the camera. Schirman juxtaposes this with footage of the only other talking head in “The Green Prince,” Yousef’s Shin Bet handler, Gonen Ben Yitzhak. As in the best fiction, these two lives intertwine in complicated, compelling fashion. Though occasionally succumbing to the tedium of its back-and-forth storytelling device, “The Green Prince” remains thought-provoking and effective. The viewer is forced to consider the lives of both men, the excruciating choices they make, and whether we would be able to make those choices.

Yitzhak tells us in the opening scene that his recruitment of Yousef was “the beginning of the end of my career.” This is contrasted with the psychological price Yousef pays for that recruitment. Yitzhak’s descriptions of how his degree in psychology allowed him to perfect the psychological manipulation of those whom he interrogated have a creepy power. Imagine someone getting into your head, wearing you down and smashing your defenses, bending you toward his or her will. Now, consider all this happening if you’re innocent.

When teenager Yousef is picked up by Shin Bet, he is under suspicion for buying guns. He says it was a teenaged mistake and had not been advised to buy weapons by any group. Since Yousef is the son of Sheikh Hassan Yousef, a leader for whom people come from miles around to hear, Shin Bet detains him.

Both Yitzhak and Yousef describe the interrogation process from opposite sides. Yousef’s description of the effects on body and mind are truly harrowing. Yitzhak tells us there was something about Yousef that indicated he might turn and spy for Shin Bet. Yousef responds that, originally, he said yes in order to stop what he’d been enduring for weeks on end. He is then sent to the Hamas section of a maximum security prison. The first question he must answer in prison is if he had been offered the opportunity to spy for Shin Bet. “If you answered no,” Yousef says, “they knew you were lying. Everyone is asked to spy.”

Yousef’s decision to become The Green Prince comes at great psychological cost. He speaks of the concept of shame in his culture, and the pain he felt in violating the almost ingrained notion of honoring one’s family. Shin Bet keeps Yousef in contact with his father and other members of Hamas, so as not to arouse suspicion. He also continues to see his mother and the younger siblings he took care of before he was imprisoned. To keep up appearances, Shin Bet has Yousef arrested multiple times, pulled from his home in the same manner his father had been during Yousef’s childhood. His father’s immediate re-incarceration six hours after being released from jail is cited by Yousef as the childhood event that fueled his anger against the Israeli army.

In the other narrative, we learn how Yitzhak violated Shin Bet’s rules multiple times to show Yousef that he could be trusted. The general rule was to be suspicious of even the most loyal spies at all times. Yitzhak meets with Yousef at one point without any other agents, which cements Yousef’s trust, and when Yitzhak discovers Yousef is burning out after 10 years of work, he makes the compassionate move that gets him fired.

“The Green Prince” gets its power from the back-and-forth of listening to each side tell its story, and from the moment the two sides converge in a final, very different collaboration in the United States. The recreations and imagery are secondary, and the overwrought score is almost always unwelcome when it bubbles up on the soundtrack. The story plays well regardless of what one’s opinion is about the conflict, because it primarily operates on the more universal, relatable aspects of human nature. One does not have to agree with the film for it to raise pertinent questions after viewing.

I found myself asking if I would be able to do what Yousef does, or if I would have been filled with more hatred after the treatment I received. I also questioned whether I agreed with Yitzhak’s methods. There were no easy answers for me, and the film offers no answers at all regarding the current situation in the Middle East. But I’m still contemplating these issues long after I’ve seen the film, which is the expected outcome of any good documentary.