The ominous approach of Hurricane Geraldo drenches the opening scenes of Robert Altman‘s “The Gingerbread Man” in sheets of rain and darkness at noon. John Grisham, who wrote the story, named the hurricane well, for like a week’s episodes of the Geraldo television program the movie features divorce, adultery, kooky fringe groups, kidnapped children, hotshot lawyers, drug addiction and family tragedy. That it seems a step up from sensationalism is because Grisham has a sure sense of time and place, and Altman and his actors invest the material with a kind of lurid sincerity.

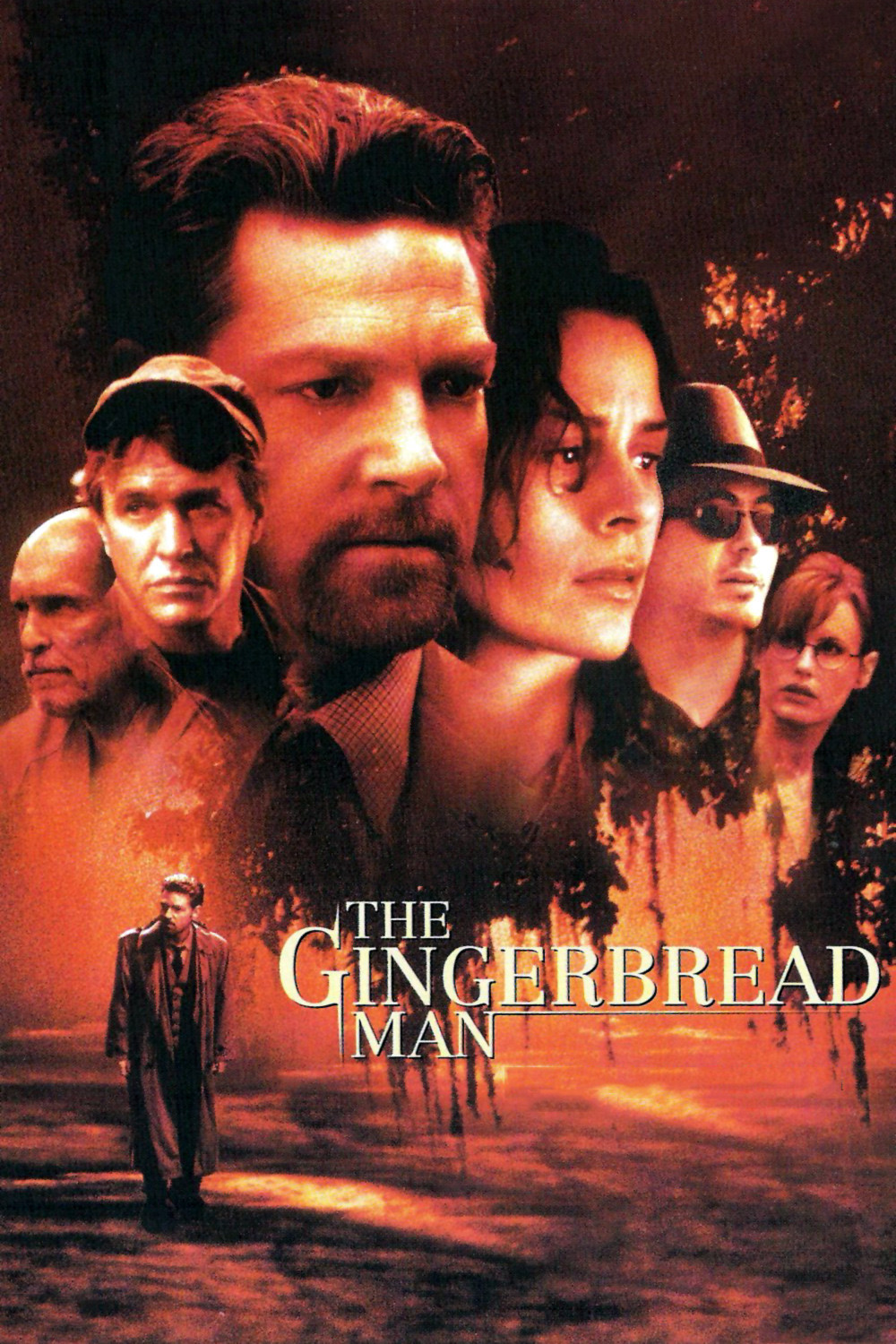

As the film opens, a lawyer named Magruder (Kenneth Branagh, Georgia accent well in hand) has won a big case and driven back to his Savannah law offices for a celebration. Awaiting him in Georgia are his faithful assistant Lois ( Daryl Hannah), his faithless estranged wife Leeanne (Famke Janssen) and his office staff, not excepting the muddled private investigator Clyde (Robert Downey, Jr.). After a catered office party at which he drinks too much, Magruder leaves for his car, only to find a woman outside in the rain, screaming after her own departing car. This is Mallory Doss (Embeth Davidtz), who was a waitress at the party, and now believes her car to be stolen.

Magruder offers her his cell phone and then a ride home, where, to their amazement, they find her stolen car. Her door is unlocked, the lights are on, a TV is playing, and she hints darkly that this sort of thing has happened before. It may be the work of her father, who belongs to a “group.” Weeping and lashing out at her absent parent, Mallory absent-mindedly undresses in front of Magruder, and as thunder and lighting tear through the sky they engage in what is categorically and unequivocally a sexual relationship.

Neat touch in the morning: Magruder prods Mallory’s prone body and, getting no response, dresses and leaves, while we wonder if she’s dead and he will be framed with the crime. Not at all. A much more complex plot is afoot, and only after the movie is over do we think back through the plot, trying to figure out what the characters planned in advance, and what was improvised on the spot.

Grisham’s story line resembles one of those Ross Macdonald novels from 30 years ago, in which old sins beget new ones, and the sins of the fathers are visited on the children. Altman’s contribution is to tell the story in a fresh and spontaneous way, to use Branagh’s quickness as an actor to make scenes seem fresh. Consider the scene where Magruder, tired and hung-over, returns to his office the next morning, marches grimly past his staff toward his office, and asks for “Some of that…you know.” As his door closes, one secretary turns to another: “Coffee.” It’s just right: Hangovers cause sufferers to lose track of common words, and office workers complete the boss’s thoughts. Lois, the Hannah character, is especially effective in the way she cares for a boss who should, if he had an ounce of sense, accept her safe harbor instead of seeking out danger.

Grisham’s works are filled with neo-Nazis, but when we meet Mallory’s dad he’s hard to classify. Dixon Doss (Robert Duvall) is a stringy, unlovely coot, and his “group” seems to be made up of unwashed and unbarbered old codgers, who hang around ominously in a clubhouse that looks like it needs the Orkin man. In a cartoon they’d have flies buzzing about their heads. In a perhaps unintentional touch of humor, the codgers can be mobilized instantly to speed out on sinister missions for old Doss; they’re like the Legion of Justice crossed with Klan pensioners.

Magruder has lots on his hands. He feels protective toward Mallory, and assigns Clyde (Downey) to her case; Clyde’s method of stumbling over evidence is to stumble all the time, and hope some evidence turns up. Magruder’s almost ex-wife, who is dating his divorce lawyer, is in a struggle with him over custody, and Magruder finds it necessary to snatch his kids from their school, after which the kids are snatched again, from a hideaway motel, by persons unknown, while the winds pick up and walls of rain lash Savannah.

It’s all atmospheric, quirky, and entertaining: The kind of neo-noir in which old-fashioned characters have updated problems. There is something about the South that seems to breed eccentric characters in the minds of writers and directors; the women there are more lush and conniving, the men heroic and yet temptable, and the villains Shakespearean in their depravity. Duvall, who can be a subtle and controlled actor (see “The Apostle“) can also sink his fangs into a role like this one and shake it by its neck until dead. And then there’s Tom Berenger as Mallory’s former husband, who seems to have nothing to do with the case, although students of the Law of Economy of Characters will know that no unnecessary characters are ever inserted into a movie–certainly not name players like Berenger.

From Robert Altman we expect a certain improvisational freedom, a plot that finds its way down unexpected channels and depends on coincidence and serendipity. Here he seems content to follow the tightly-plotted maze mapped out by Grisham; the Altman touches are more in dialog and personal style than in construction. He gives the actors freedom to move around in their roles. Instead of the tunnel vision of most Grisham movies, in which every line of dialog relentlessly hammers down the next plot development, “The Gingerbread Man” has space for quirky behavior, kidding around, and murky atmosphere. The hurricane is not just window dressing, but an effective touch: It adds a subtle pressure beneath the surface, lending tension to ordinary scenes with its promise of violence to come.