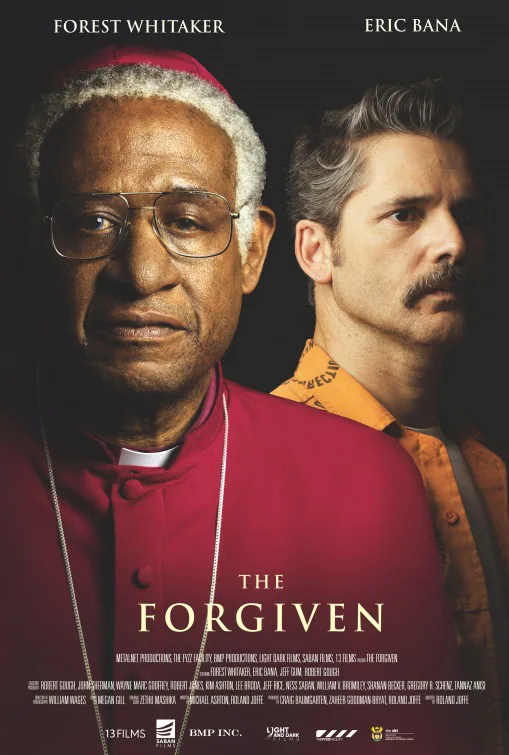

I’m not really sure how “The Forgiven,” a drama about post-apartheid reconciliation, could have worked given its creators’ unfortunate habit of pushing viewers’ buttons with violence and racial slurs, and then hoping we still feel like turning the other cheek. Writer/director Roland Joffe (“The Killing Fields,” “Captivity”) and co-writer Michael Ashton—the latter of whom wrote the film’s source play, “The Archbishop and the Antichrist”—may have based their characters and situations on real life, though the real-life Archbishop Desmond Tutu (Forest Whitaker) never considered amnesty for fictional South African death squad assassin Piet Blomfeld (Eric Bana). But that doesn’t excuse their demeaning consideration of Blomfeld’s crimes. By focusing so much on Blomfeld’s personality instead of his victims’ family members, Joffe and Ashton don’t just come across as insensitive, but also knowingly exploitative.

Just look at the way that Blomfeld’s crimes are primarily considered through the lens of his repugnant personality. Bana gives Blomfeld a swaggering bravado to match his Freddie Mercury-looking tache, and it makes his character’s constant use of the “kaffir” racial slur even more sickening. Blomfeld also plainly lays out his disgusting worldview during a preliminary interrogation scene that serves a weirdly similar function to the one in “The Dark Knight.” The main difference is that the Joker doesn’t go as far as Blomfeld, who boasts about dreaming of a Charles Manson-esque race war where the inevitable “winner who emerges will be white.” Blomfeld also tells the Archbishop frankly that he’s “killed lots” because he enjoys it, and only submitted a request for amnesty that features quotations from Milton and Plato because he knew the Archbishop could not resist such a challenge.

Still, the Archbishop takes Blomfeld’s bait, partly because the former man is the leader of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. The Archbishop—still with us—also believes in the Committee’s goal of forgiveness. Unfortunately, Joffe and Ashton don’t try very hard to get viewers to see the world through the Archbishop’s eyes. Most of his perspective is broken down through solemnly intoned fortune cookie speechifying, like “Brutality is the aberration, Mr. Blomfeld, not love,” and “You cannot change what is over, or where you have been. But you can change where you now go.” There’s nothing theoretically wrong-minded about asking viewers to applaud the Archbishop’s saint-like patience. But these platitudes sting when they’re dispensed in a film that spends way too much time with Blomfeld as he taunts, snarls at, and insults everybody within earshot.

Worse still: there are only three other types of normalizing scenes in “The Forgiven”:

1) A distracting sub-plot concerning “the 28’s,” a gang of black South African prisoners who are depicted as being highly territorial, and violent. Members of the 28’s, including neophyte Benjamin (Nandiphile Mbushu), don’t ever talk about what makes them so angry or vicious. In fact, this sub-plot doesn’t really have a resolution, save perhaps for a scene where Blomfeld teaches Benjamin to remove blood-stains with vinegar, and then makes a vague pronouncement about how prison is “the best school.”

2) Hackneyed domestic scenes between the Archbishop and his wife Leah (Pamela Nomvete) where she dotes on his health, and gives him hot cocoa while he pontificates about his ideals, like when he tells her he can’t even describe how joyous Nelson Mandela’s election was after decades of political corruption. These scenes come straight out of the Great Man Theory of History playbook, and are so shop-worn that they don’t emotionally register.

3) Brief trial scenes where white racists are put on trial, and made to confront their victims’ families. These scenes are too brief, and rely too much on the emotional strength of actors playing indignant and/or weepy convicted murderers (almost all of whom deliver one-note performances).

In this context, Joffe and Ashton’s focus on Blomfeld is sadly revealing. They spend more time needling viewers than they do leading us to an understanding of forgiveness. For further proof, just see the brief scene where a grieving mother asks the Archbishop to find for her one piece of her dead son’s body (he was buried in a mass grave). If the Archbishop can grant her this one solace, she can give her son “a proper burial.”

This line made me realize just how manipulated I felt by “The Forgiven.” I have no personal connection to the acts of violence depicted in the film. But I can imagine how furious I’d be if Joffe and Ashton applied a similar approach to a drama about Holocaust remembrance that also emphasized the attitude and not the impact of one especially heinous Nazi. A crime isn’t noteworthy for its perpetrator’s viciousness, but rather the burden of loss it places on the people who remain. Joffe and Ashton show no such understanding, and “The Forgiven” consequently only succeeds as an ugly, empty-headed provocation.